Releases from Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Maggie Nicols/Robert Mitchell/Alya Al Sultani, and Gordon Beck Trio and Quintet

UNEXPECTED: Tirana adventures in architecture

[Pic: Z Blace/CC]

UNEXPECTED: Tirana adventures in architecture

[Pic: Z Blace/CC]

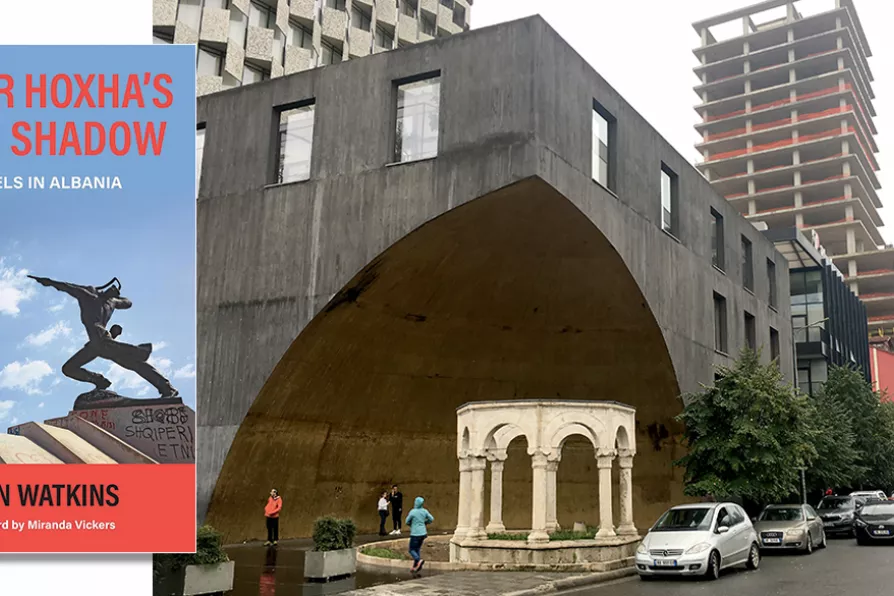

Enver Hoxha’s Long Shadow – Travels in Albania

John Watkins, Signal Press, £14.99

ALBANIA is an anomalous and perplexing country to many outside of it: a heartland of European Islam and long an atheist country, dominated by a language that has no close relatives, geographically a wild mix of forest, mountain and sandy beaches, but firmly associated with brutalist cities, heavy industry and metal mining.

Surrounded by the tumultuous history of Greek and Balkan nations, Albania has remained apart through the centuries. Both despite and because of its long domination by the Ottomans, then the Italians and the Nazis, it has forged a strong and unique national identity. Yet its people are spread around the world, with more Albanians in the diaspora than living in the country.

Albania remains perhaps the most exotic place in Europe.

ALEX HALL follows the battered fortunes of Syria, a multi-ethnic country caught in the crossfire of competing imperialist interests

HENRY BELL notes the curious confluence of belief, rebuilding and cheap materials that gave rise to an extraordinary number of modernist churches in post-war Scotland

MARJORIE MAYO recommends a disturbing book that seeks to recover traces of the past that have been erased by Israeli colonialism