GORDON PARSONS applauds a marvellous story of human ingenuity and youthful determination, well served by a large and talented company

HENRY BELL is provoked by a book that looks toward, but does not fully explore the question of who gets to imagine the shapes of cities to come

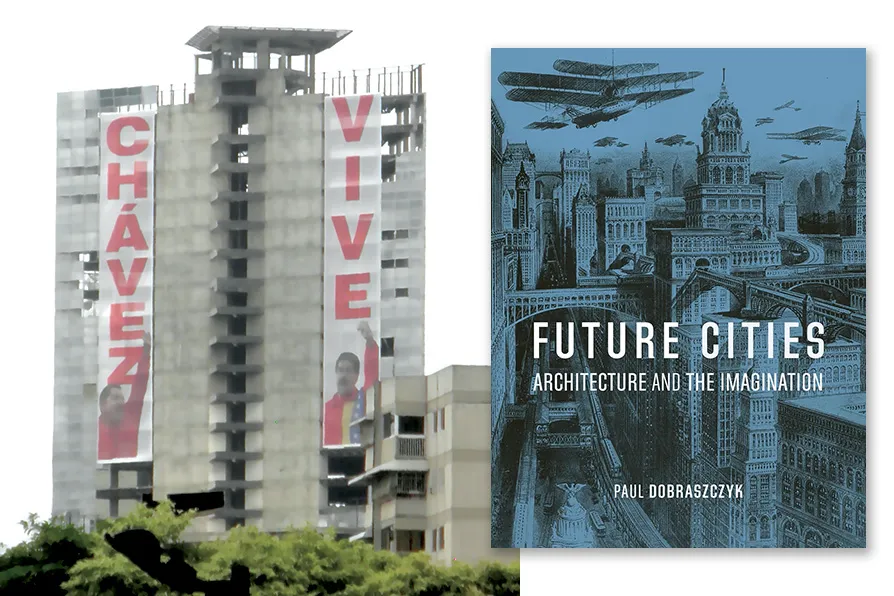

Centro Financiero Confinanzas (Torre David/David Tower) draped with banners saying 'Chávez Lives' in October 2014 / Pic: Hernan Zamora/flickr/CC

Centro Financiero Confinanzas (Torre David/David Tower) draped with banners saying 'Chávez Lives' in October 2014 / Pic: Hernan Zamora/flickr/CC

Future Cities: Architecture and the Imagination

Paul Dobraszczyk, Reaktion, £18

ALASDAIR GRAY wrote in his classic novel Lanark – itself a multidecade exploration of the city as a symbol:

“Glasgow is a magnificent city … Why do we hardly ever notice that? … Because nobody imagines living here … think of Florence, Paris, London, New York. Nobody visiting them for the first time is a stranger because he’s already visited them in paintings, novels, history books and films. But if a city hasn’t been used by an artist not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively.”

In his book Future Cities Paul Dobraszczyk lives imaginatively in the cities of the future, and in the future cities of the past. By exploring what artists, novelists, town-planners and film-makers have projected onto the future of the city, Dobraszczyk undertakes a cultural enquiry into where the city is going next.

The book takes fictional cities not as mere fantasies but as potential way-markers, exploring the tight-knit relation between the vast imagined tomorrow and the real future that the world’s urban rich and poor are often blindly crawling towards. It is a book that, at its heart, understands that the future tells us more about the present than it does about anything else.

What are the material realities that produce our imagined future cities? High rise and subterranean cities tell us about rapid population growth and stark inequality. Unmoored, flying and floating cities speak to climate change and the rising seas. Linear cities envisage the ongoing eradication of distance. Verdant domed cities belie a future of poisoned and unbreathable air. Salvaged and ruined cities show us a future of technological, legal or even societal collapse. All of these future cities answer questions of our present moment.

The cities in this book are speculative and they are real. The author in fact illustrates that all cities must be both — a city being, by definition, something that has been too great to be held in the mind. As cities around the world become increasingly vast and disorienting and their futures begin to feel increasingly homogeneous, this book gives us a refreshing tour of the diverse future cities of the past, but it also points to the real cities of the future that are already being built. They are at once imagined and real.

In doing so the book often looks toward, but does not fully explore the question of who gets to imagine the future. To misquote Marx: the futures of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling futures.

As what Richard Seymour has dubbed Disaster Nationalism takes hold from India to Israel to America, the cities of the imagined future paint a disturbing picture of societal despair and growing apartheid. Dobraszczyk notes Mike Davis’s observation that if current trends continue then more than half the world’s population will soon live in the self-built slums known as favelas, barrios, bustees, and shanty towns. The future city is not built of glass and steel, but salvage and iron. The dystopian cities of Soylent and Robocop feel closer than ever in a MAGA world.

Dobraszczyk also however presents imaginaries in which such self-build communities represent empowerment, kinship, and bottom up power. He links such ideas to real city experiments such as the 3,000 squatters who lived in Torre David in central Caracas, embracing the Chavismo call to appropriate redundant capitalist property. In Britain, the artists’ collective Assemble (who won the Turner Prize in Glasgow in 2015) present a parallel image of salvage, reclamation and democratisation of the city.

Much like such projects of salvage and reclamation, Future Cities is an experiment in the aggregation of human ideas, a masterful tour of the urban imaginary that spreads out like a city, with countless neighbourhoods to explore.

HENRY BELL notes the curious confluence of belief, rebuilding and cheap materials that gave rise to an extraordinary number of modernist churches in post-war Scotland