GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

The barricade moment

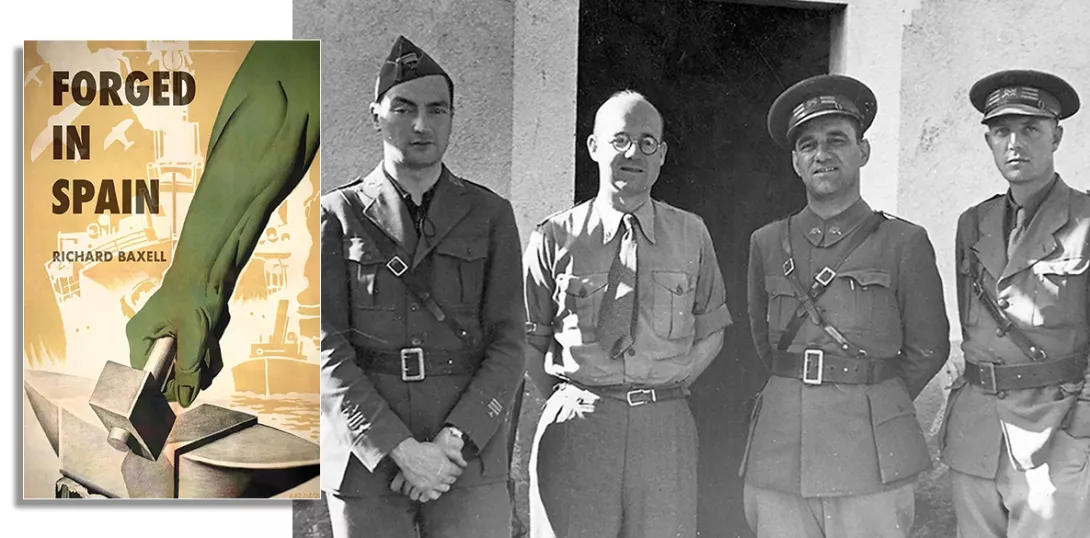

HELEN MERCER admires a skilful telling of 12 personal histories of engagement with the Spanish civil war

Forged in Spain

Richard Baxell

Clapton Press, £16.99

RICHARD BAXELL’s new book has 10 chapters which provide short yet detailed and vivid biographies of 12 of those who fought in the Spanish civil war.

Seven were International Brigaders (Malcolm Dunbar, Sam Lesser, Peter Kerrigan, Alexander Foote, Clive Branson, Alex Tudor-Hart and Ronnie Burghes). One fought with the POUM (Stafford Cottman) and one with Franco’s forces (Peter Kemp).

Leah Manning is remembered for her role in ensuring the evacuation and settlement in Britain of Basque children.

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

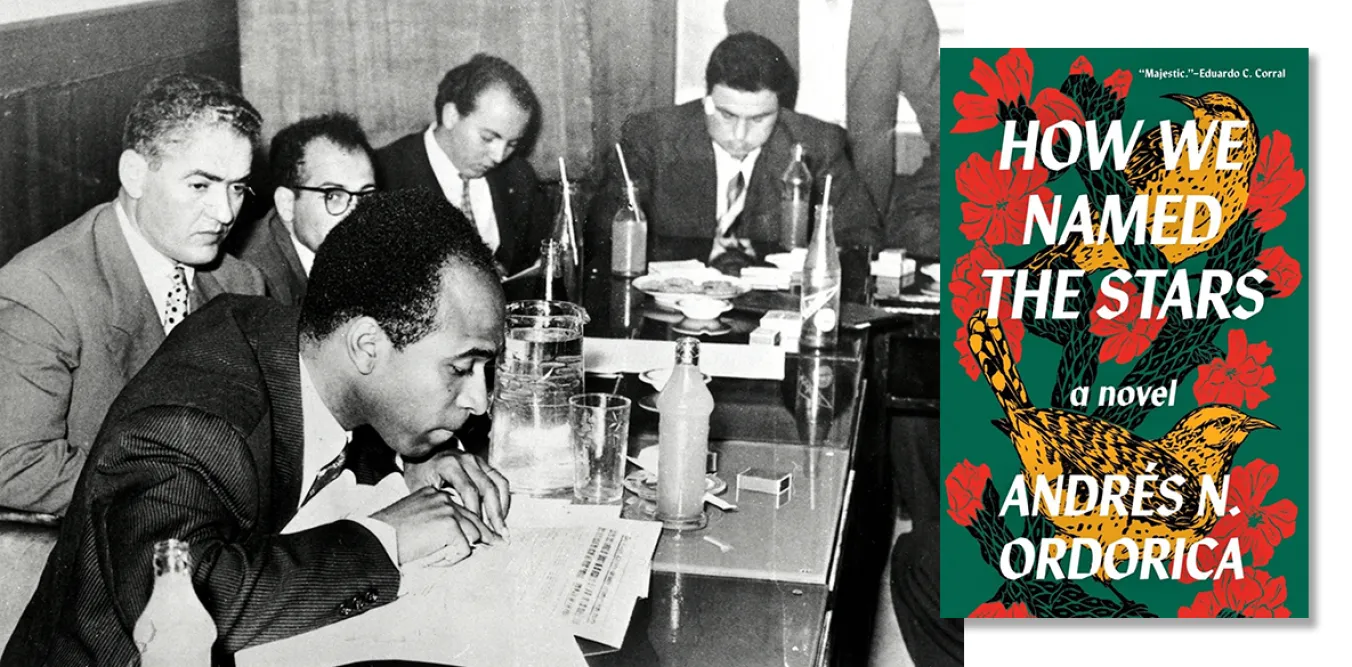

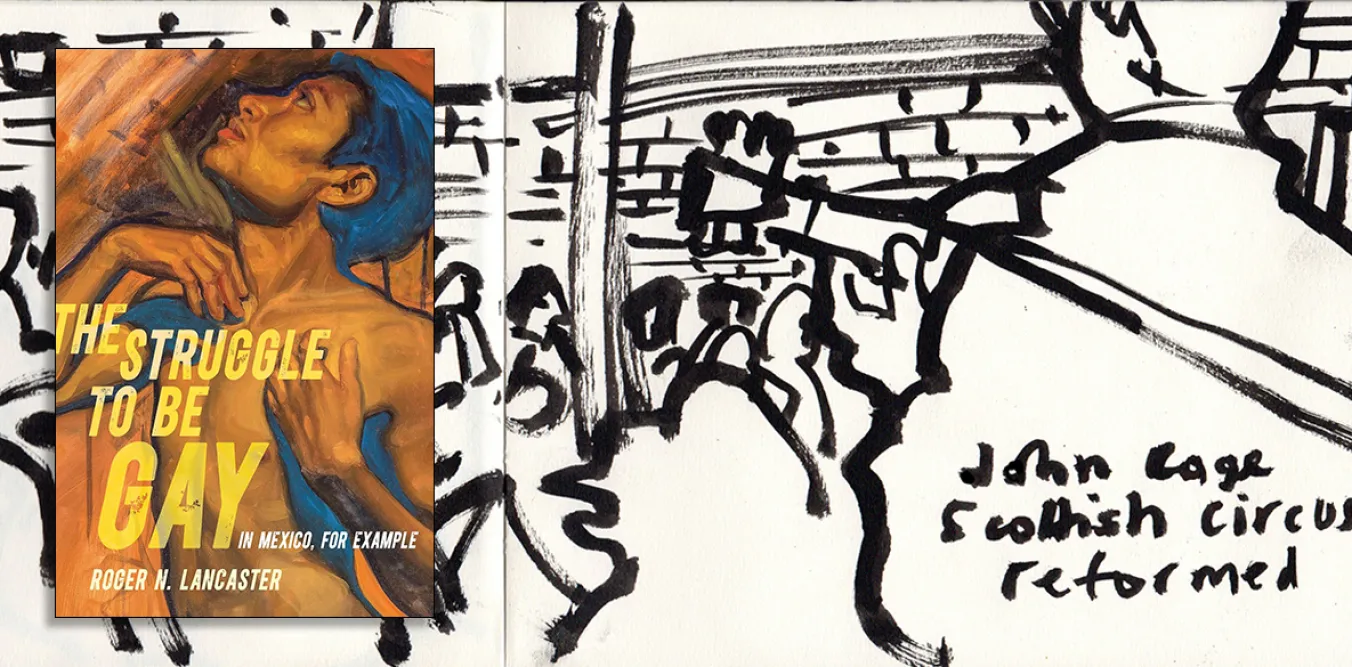

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

JACK YOUD explains why local activists and trade unionists are raising funds to honour the city’s volunteers who fought for liberty in Spain

TONY FOX reports from a Hartlepool event to commemorate those from the area who went and fought for liberty in Spain

This year’s International Brigade Memorial Trust

commemoration took on an urgent tone, with

warnings of ‘terrifying wave of fascism’ in Europe

drawing parallels between 1930s Spain and

today, reports LYNNE WALSH

Teaching youngsters about the International Brigades and the Spanish civil war is vital for a proper understanding of 20th-century history, writes JIM JUMP