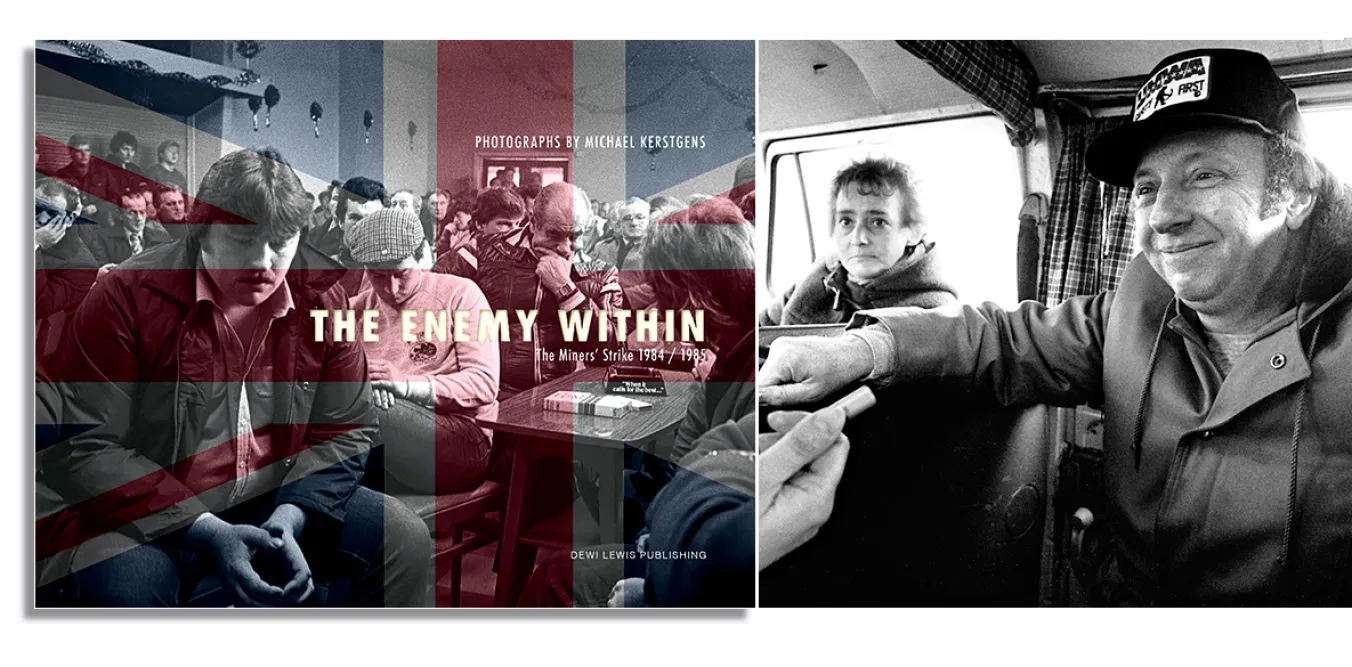

The Enemy Within - The Miners Strike 1984/85

By Michael Kerstgens

Dewi Lewis, £35.00

THIS photo album is an unusual one in showcasing images taken by a young German student who, almost by accident, became intimately involved in the big British miners’ strike of 1984/85.

Michael Kerstgens’s book documents the lives and struggles of the strikers based in the village of Wombwell, near Barnsley in the Yorkshire coalfield. As a hard-up student, he was generously taken in by a local miner, Stuart “Spud” Marshall and his wife, Marsha, who lived in a small, terraced house, along with their son, Mark, daughter, Jill, and Jill’s boyfriend.

He relates: “From the window of his house, you could see the strikebound Darfield Main Colliery. So it was that I landed right in the middle of one of the most bitter industrial conflicts that the UK has ever seen. It was agreed I could stay for as long as I liked, accompany them wherever they went, and, most important of all, take photographs.