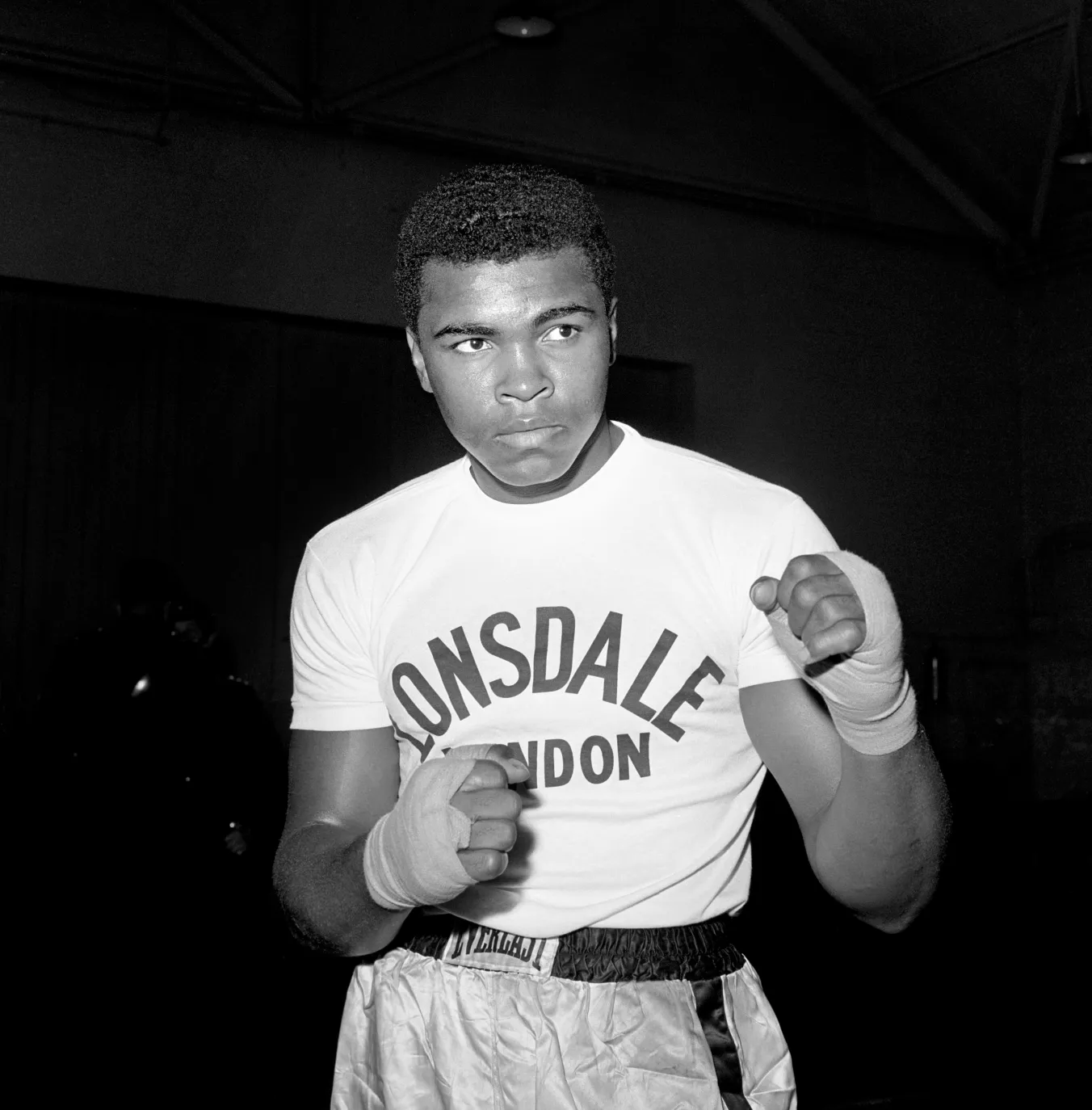

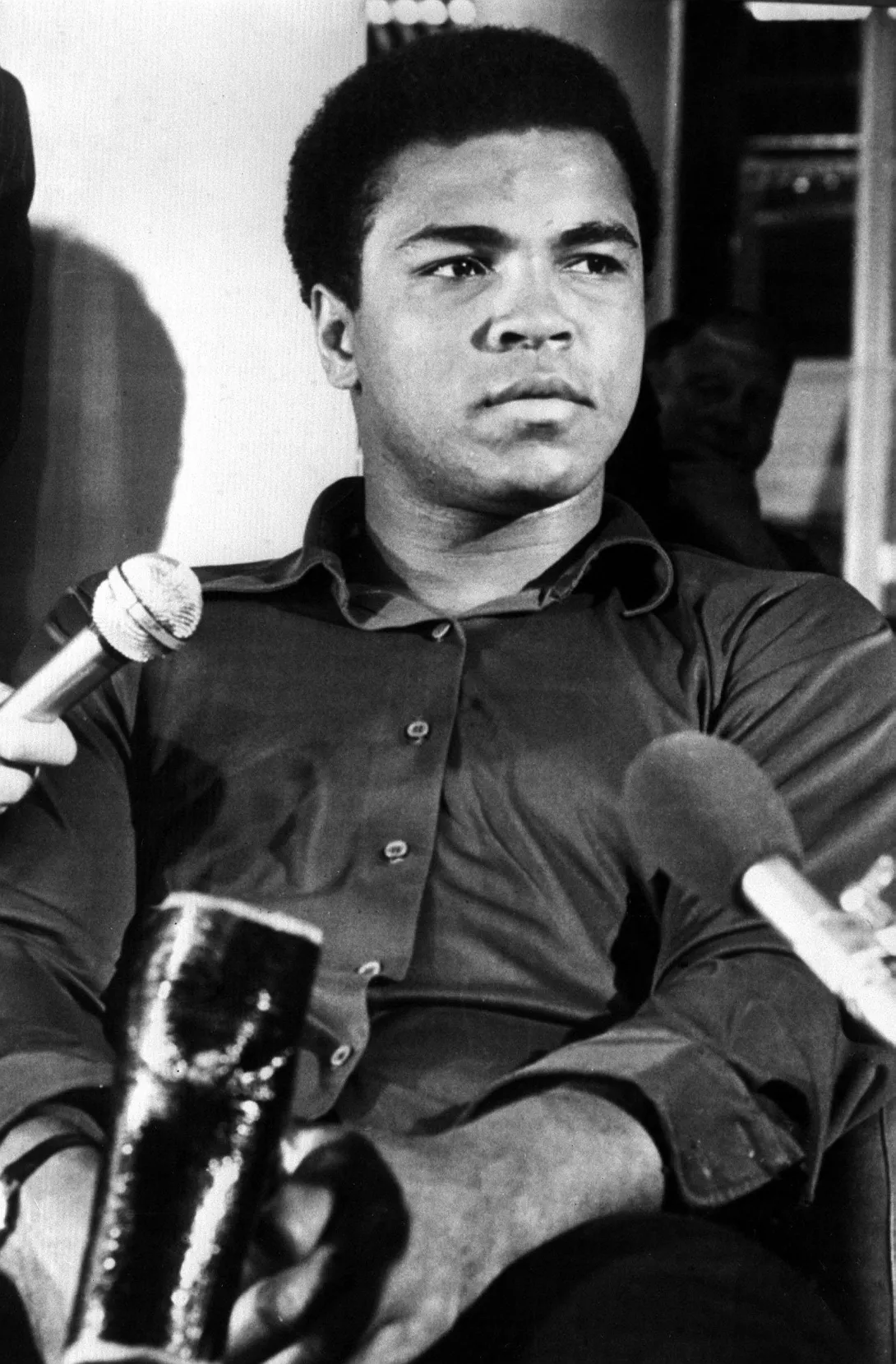

ROBERT BURNS and Muhammad Ali are not historical figures you would ever expect to see named in the same sentence, but back in 1965 their paths actually did cross.

Ali came to Scotland in August of that year to fight an exhibition bout at the old Paisley Ice Rink against his long-time friend and sparring partner Jimmy Ellis. Waiting to meet and greet him off his flight were the women of the Braemar Ladies Pipe Band from Coatbridge. Replete in highland regalia, they piped him down the steps of the aircraft onto the tarmac at what was then Renfrew Airport in Glasgow.

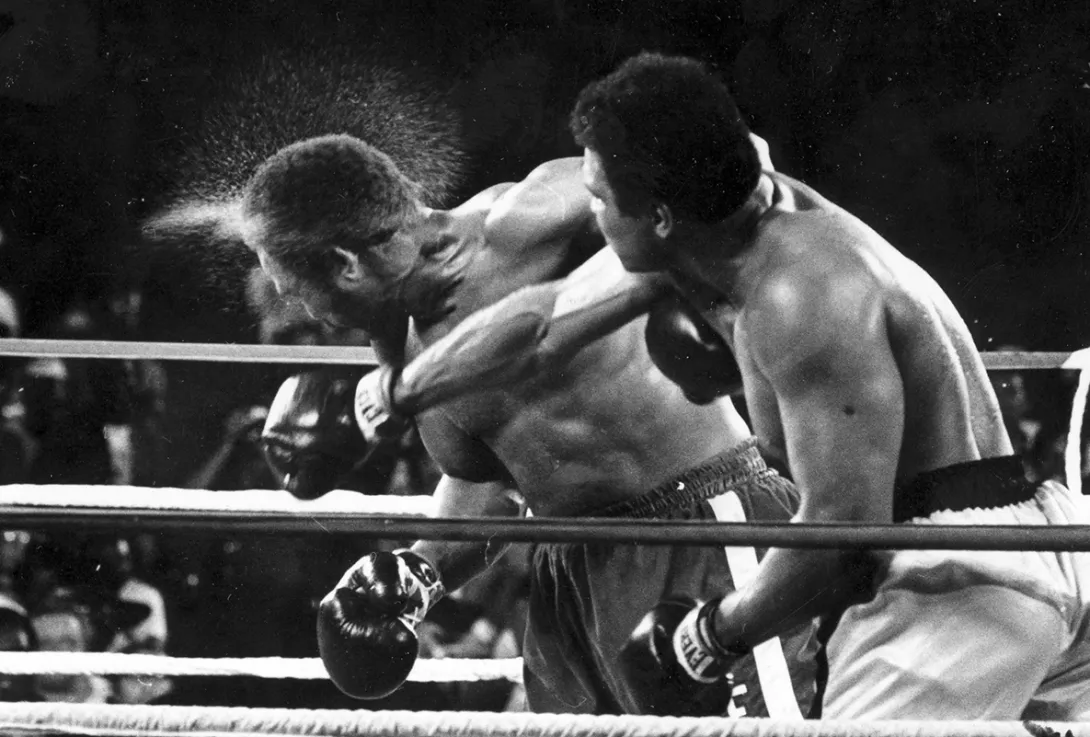

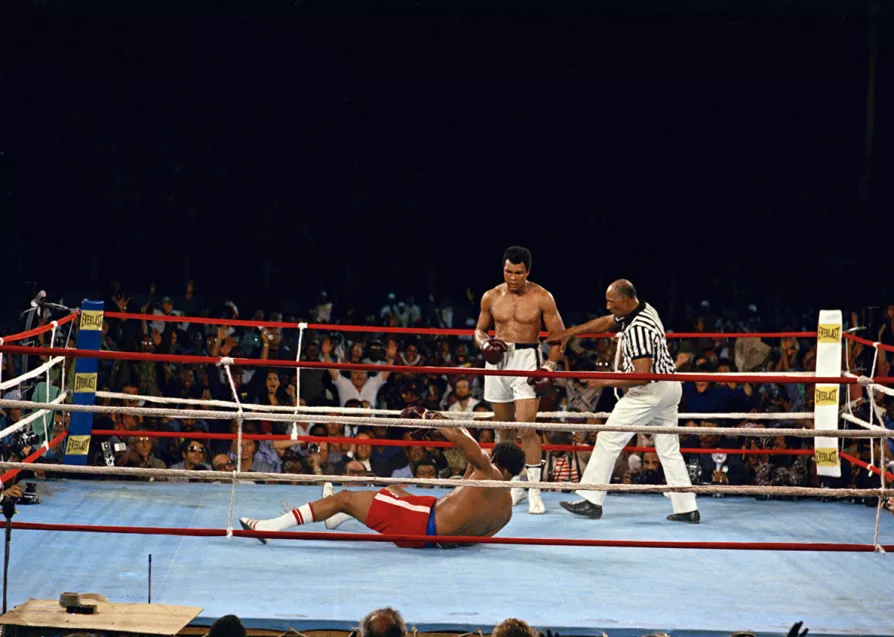

The year 1965 had been a turbulent one for the heavyweight world champion up to this point. In February his former mentor, friend and spiritual guide Malcolm X was assassinated at the hands of the Nation of Islam, following a deeply angry and acrimonious split. The fallout saw Ali receive death threats in advance of his May rematch against Sonny Liston in Lewiston, Maine. Ali won the rematch in controversial fashion with his now legendary “phantom punch,” with many claiming still to this day that Liston took a fall on orders from the mob, who controlled Liston’s career.