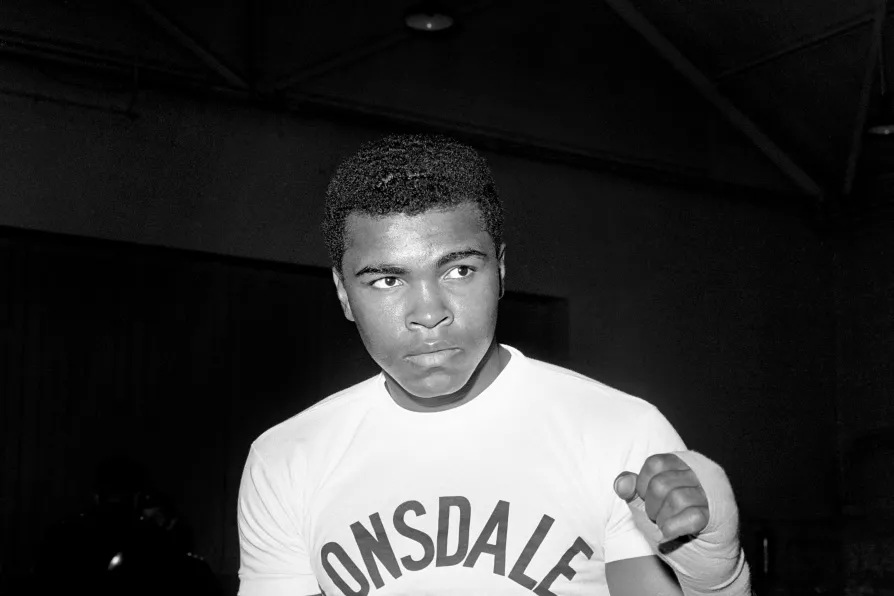

Boxer Muhammad Ali during a training session at the Territorial Army Centre in White City, London, May 29, 1963

Boxer Muhammad Ali during a training session at the Territorial Army Centre in White City, London, May 29, 1963

AS WITH the “Santa Clausification” of Martin Luther King over the years, so the Santa Clausification of Muhammad Ali has served to elide from his life and legacy, almost completely, the man’s radical consciousness and the positions he took based upon it.

We are all familiar, of course, with Ali’s stand in opposition to the US imperialist war in Vietnam, and of how he sacrificed the prime years of his boxing career in taking this stand.

He became a worldwide symbol of defiance against the injustice perpetuated by his government abroad, and a champion of the black liberation struggle at home.

JOHN WIGHT tells the riveting story of one of the most controversial fights in the history of boxing and how, ultimately, Ali and Liston were controlled by others