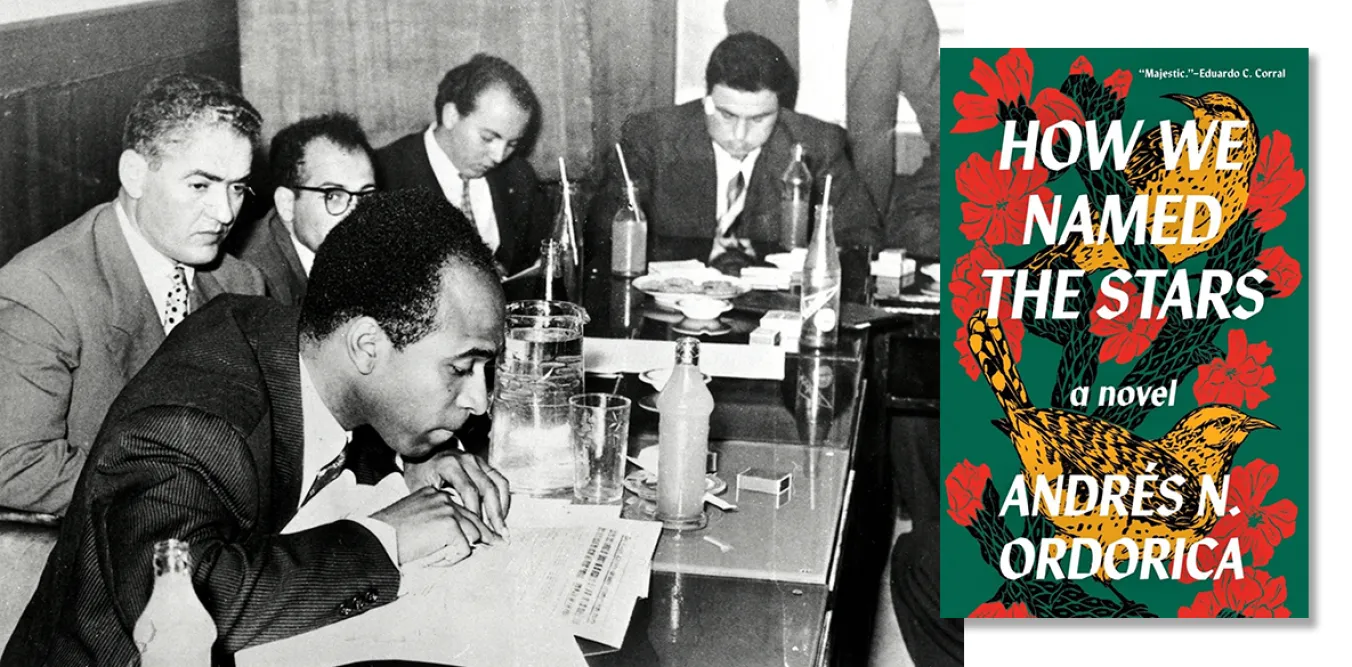

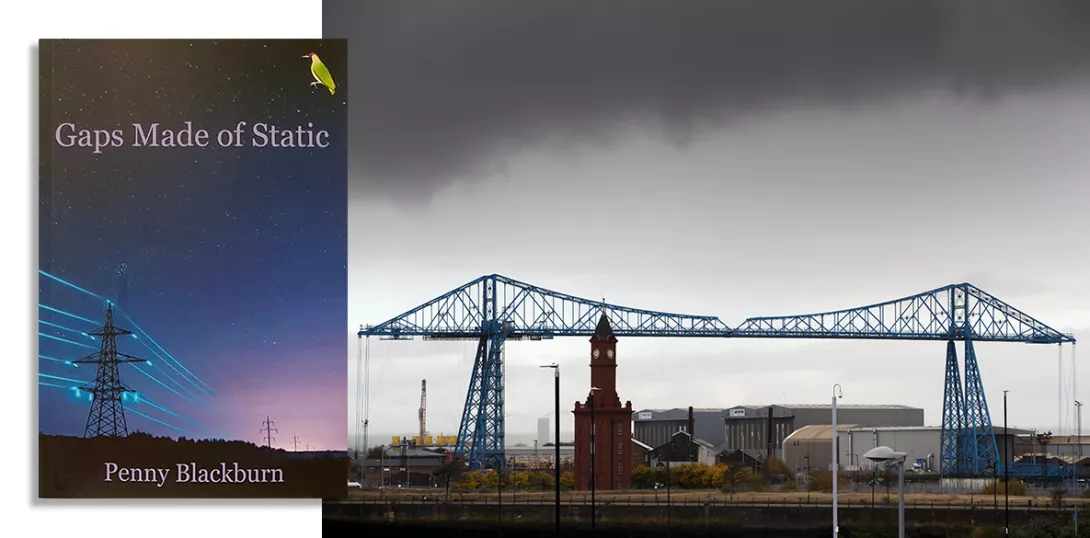

Gaps Made of Static

Penny Blackburn, Yaffle Press, £11.50

PENNY BLACKBURN, were you to break her in half a la the old “Blackpool rock” gag, her remains would read — much like mine — Northerner, right through, top to bottom.

Fiercely proud of her roots, steeped as she is the traditions of working-class life in her native Huddersfield, the wanderings of her pen are spread fairly evenly between the heavy engineering heritage of the north, and that hoary old subject which remains rather more difficult to pin down: poetry based on the rich and varied everyday lives of ordinary people.

Published by Yorkshire-based Yaffle Press, a cursory flick through this collection’s pages reveals its heart to be equal parts tough/tender. To reach behind the rather fetching front cover is to inhabit a museum world of cobbles, mineshafts, railway cuttings, pylons, Roman walls, boatyards and their blackened rivers. Here be ghosts.