GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

An uneven piece that never fully lands

MARY CONWAY is disappointed by a play that often leaves the audience with too little to hold on to as the main thrust of the story

The Ballad of Hattie and James

The Kiln

IT’S a great story. Talented pianists Hattie and James meet when they’re 16. He progresses through life as a musician while she drops away: another great woman casually junked from the roll call of history.

Only when she, one day, spontaneously pours out her soul with a public performance on the piano at St Pancras International does she suddenly garner fame by going viral on the internet.

A truly gender-driven triumph!

More from this author

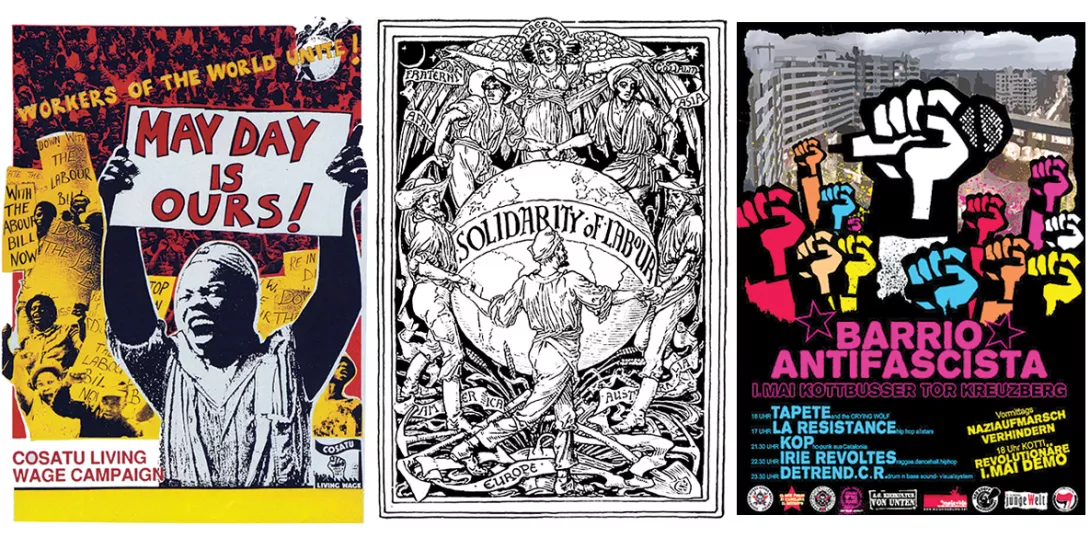

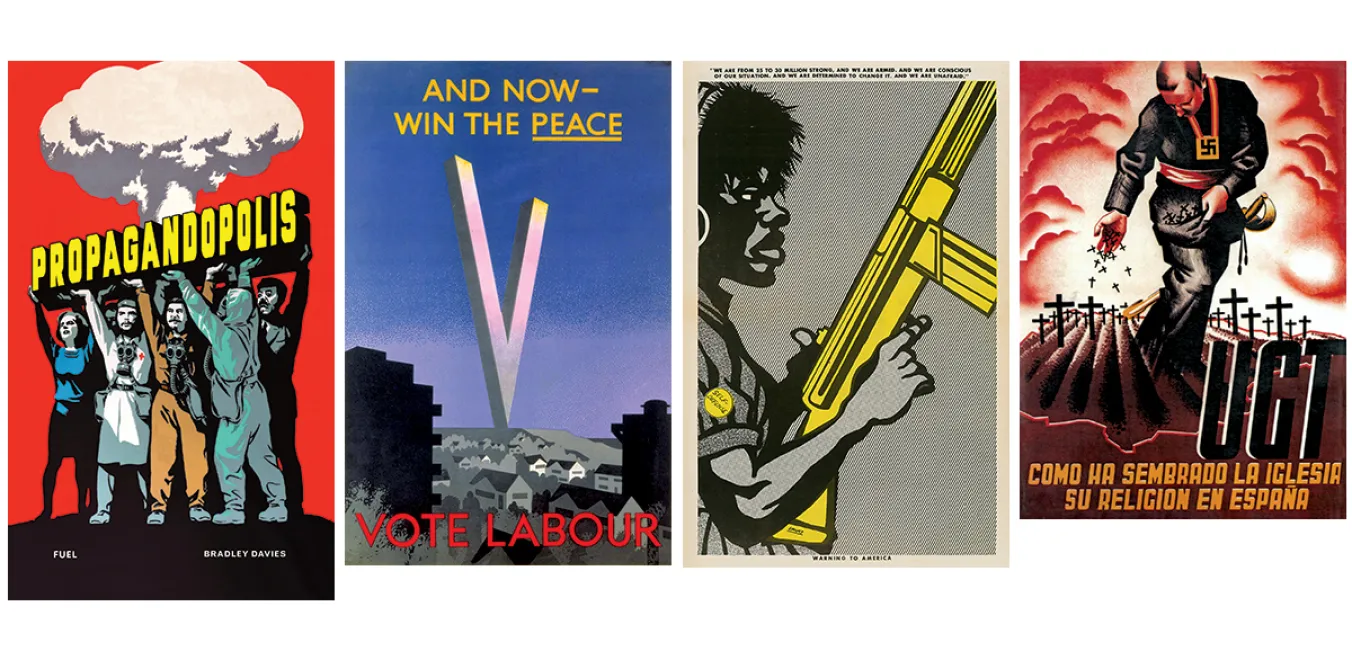

MICHAL BONCZA recommends a compact volume that charts the art of propagating ideas across the 20th century

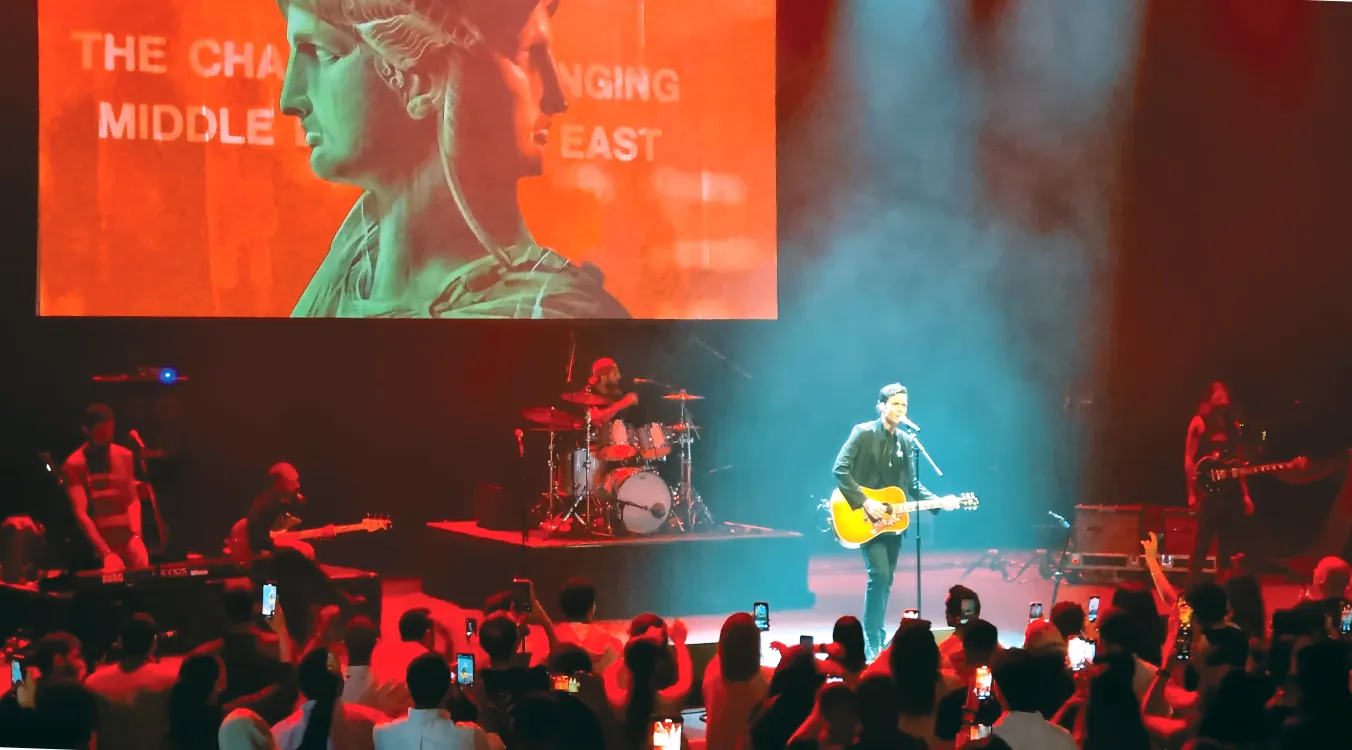

MICHAL BONCZA reviews Cairokee gig at the London Barbican

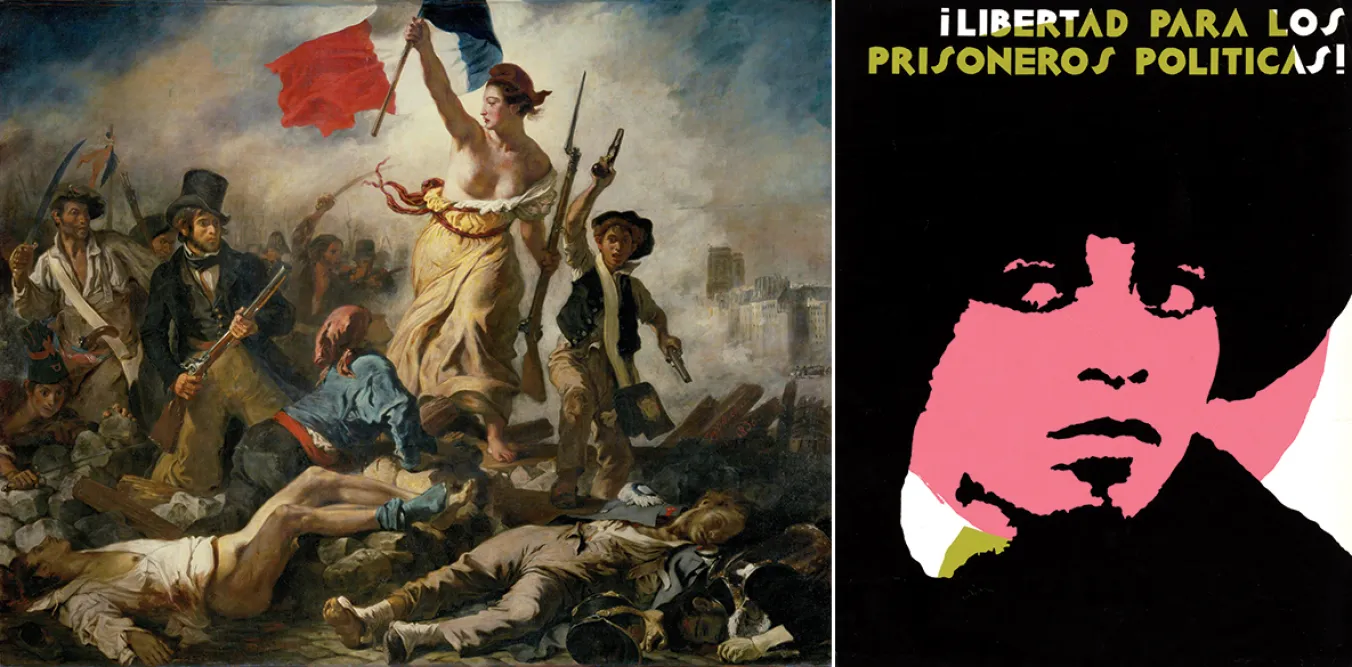

MICHAL BONCZA rounds up a series of images designed to inspire women

Similar stories

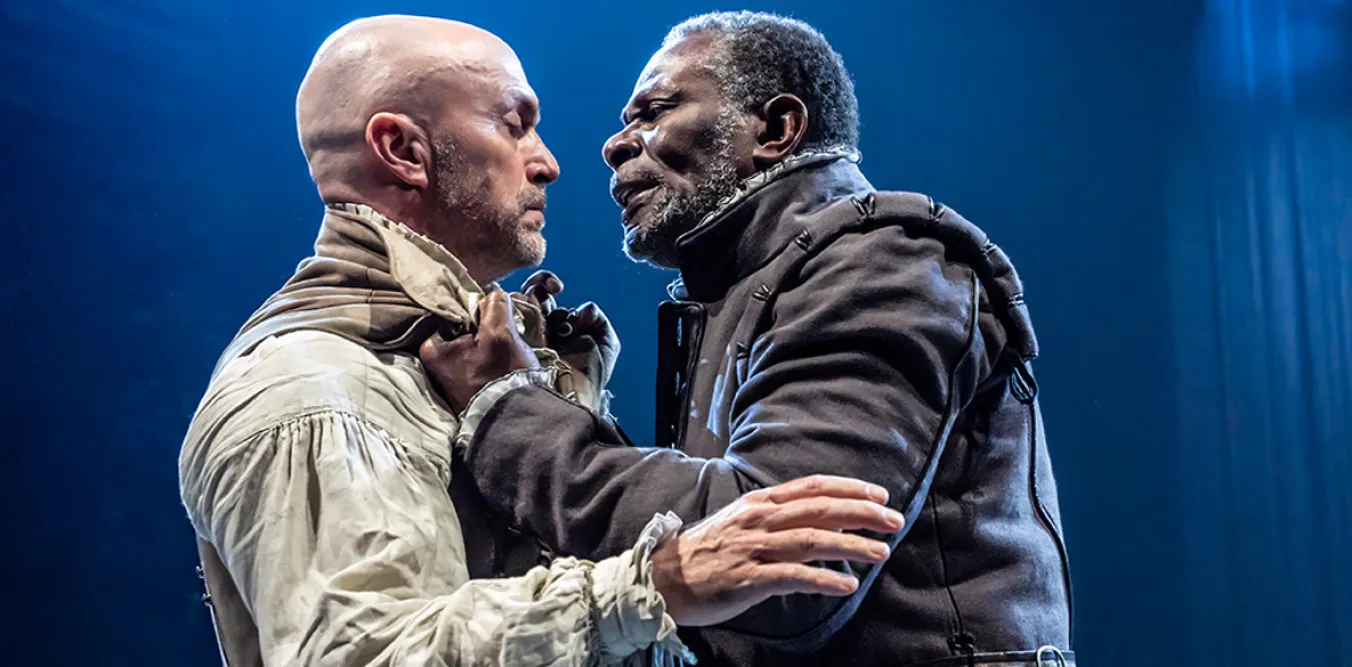

GORDON PARSONS hails a magnificent performance by a cast who make sure that every word can be heard and understood

James Brandon Lewis Quartet, Art Tatum Trio and Kevin Figes

EWAN KOTZ is impressed by the continuing creativity of a five-piece that rues the ruthlessness of capitalism in Australia

GORDON PARSONS is thrilled by the dramatisation of the relationship between a gay composer and his unmarried female assistant