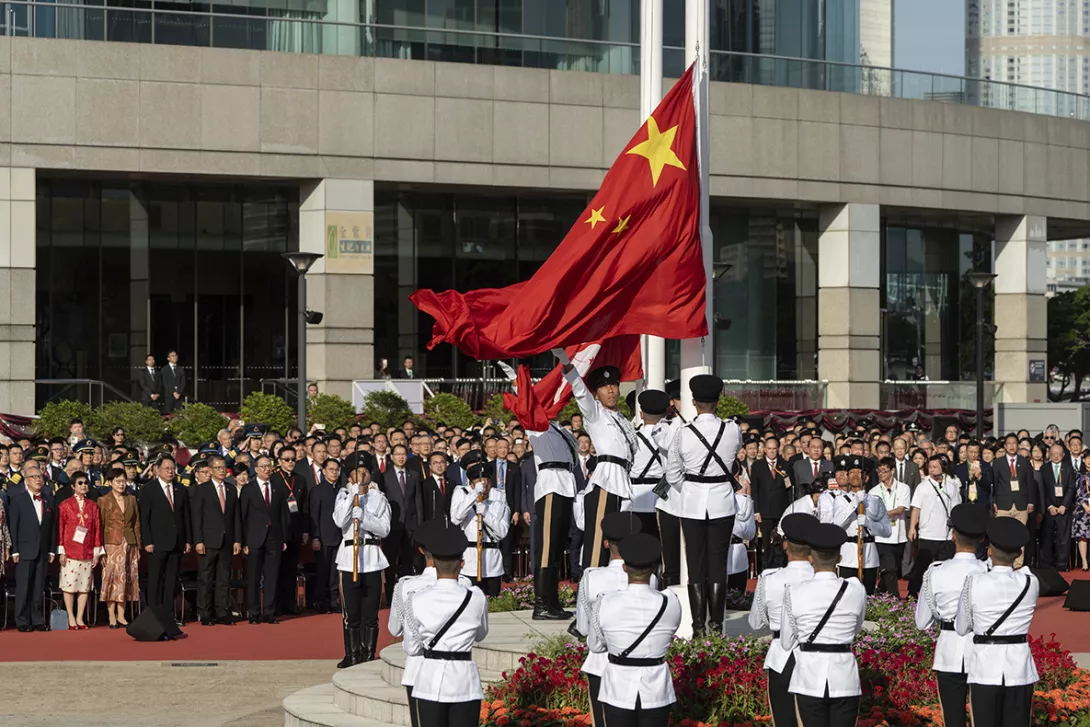

AT A TIME when the crumbling leadership of the fading West is doing all it can to bring about a shooting war with China, and the media instructs us daily to hate and fear everything from that country, it’s mildly surprising to see launching a major series based on one of this century’s biggest Chinese bestsellers.

I don’t imagine author Cixin Liu is shocked, though. Every chapter of his multiaward-winning trilogy demonstrates that he grew up in an educational system which understands that contradictions are an engine of human history. The law of unintended consequences is one of his principle plot devices.

Scientists in Three-Body Problem (the first volume) find a solution for the Fermi Paradox, the puzzle which asks “Since the universe must be full of life, where are all the aliens?”