The suicide of Tamara Jade Logon after her disability benefits were wrongly withdrawn is the latest in a series of deaths in which coroners have cited DWP failings, exposing a pattern of preventable harm, says DYLAN MURPHY

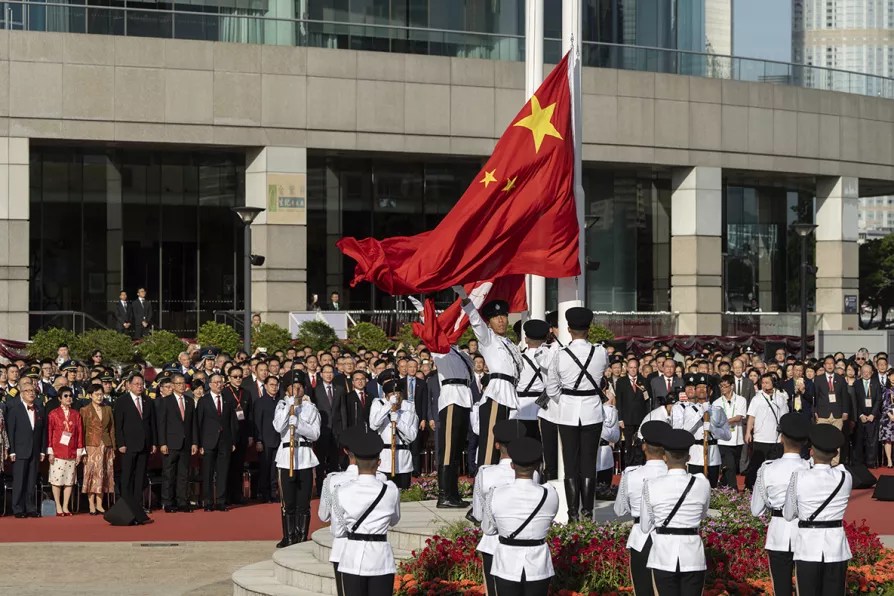

A Hong Kong police guard of honor rises China and Hong Kong flags during a flag raising ceremony for the celebration of the 75th National Day of the People's Republic of China in Hong Kong, October 1, 2024

A Hong Kong police guard of honor rises China and Hong Kong flags during a flag raising ceremony for the celebration of the 75th National Day of the People's Republic of China in Hong Kong, October 1, 2024

“OH NO … now I understand why they don’t want us to read this stuff.”

Yu is looking a little downcast. She holds my phone and checks the screen again, the Guardian article on China she’s just finished reading.

If you believe the Guardian journalist, borders are currently thronged with “desperate” Chinese migrants trying to “escape” their country. The article is a dissonant read for those of us comfortably seated under trees in a quiet corner of Beijing, one of the most modern, well-run cities in the world.

To be more precise, we’re on a campus, in the green spaces between halls of residence. Since I began life as a mature student here, I have counted four large cats, overfed by a keen student population, and five hedgehogs, including the babies, which is five times more than I ever spotted in Somerset when I lived there.

It’s the evening, and Yu and I are surrounded by young students walking back to their dorms from the showers building, many of them already in pyjamas. She points at the article again. “They take one truth, and they say something completely false about it. Look, they write about ‘runxue’. It’s a made-up word that combines the English, to run, and the Chinese xue, to study.”

The Guardian journalist hasn’t bothered to translate the word, of course, because it becomes quite benign when you know its meaning. It was coined for students from well-off families who feel “it’s too competitive in China and decide to go abroad to study,” Yu says. The image of “desperate” Chinese migrants is receding further away.

I have a few runxue among my friends. One did an MA in computer studies, the other a PhD in philosophy, both in Britain, and both left after a few years to return to China. They did so for a variety of reasons.

The most business-minded saw that China, not London was the land of economic opportunity after all, and it was time to go back. The philosopher got sick of the anti-China propaganda and constant misreading of his culture and history, not only by British society but by his socialist friends, his professors. He got tired of having to explain himself to people.

If you meet Chinese people in Britain, you will notice that they will often decline all political discussions by ignoring them. As if they haven’t even heard your question. Why should they talk with people who don’t even bother to scratch behind the headlines?

There’s one way to break the ice though, which I use all the time. I told my online Chinese teacher once, “I don’t read the BBC, why bother?” She asked, “Because they lie?” I said, “Yes, it’s all bullshit.” So she taught me how to say “fake news” in Chinese: jia xinwen.

I didn’t see Yu yesterday because she spent most of the day in bed. It was National Day in China, and 75 years since the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

MATT KERR charts his bike-riding odyssey in aid of the Royal Marsden charity and CWU Humanitarian Aid

The Labour Party proposal to scrap benefits for those unable to work will be debated in Parliament next Tuesday, and threatens the most vulnerable in our society. ALAN MORRISON presents some responses in poetry

‘Chance encounters are what keep us going,’ says novelist Haruki Murakami. In Amy, a chance encounter gives fresh perspective to memories of angst, hedonism and a charismatic teenage rebel.

It’s tiring always being viewed as the ‘wrong sort of woman,’ writes JENNA, a woman who has exited the sex industry