GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

Class menagerie

FIONA O’CONNOR assesses a dense and overpopulated novel that isn’t satire and doesn’t go deep

Caledonian Road

Andrew O’Hagan

Faber, £20

FREDERIC JAMESON used the term “national allegory” for the view that literature is really an attempt to discover a country’s identity, and therefore its inhabitants.

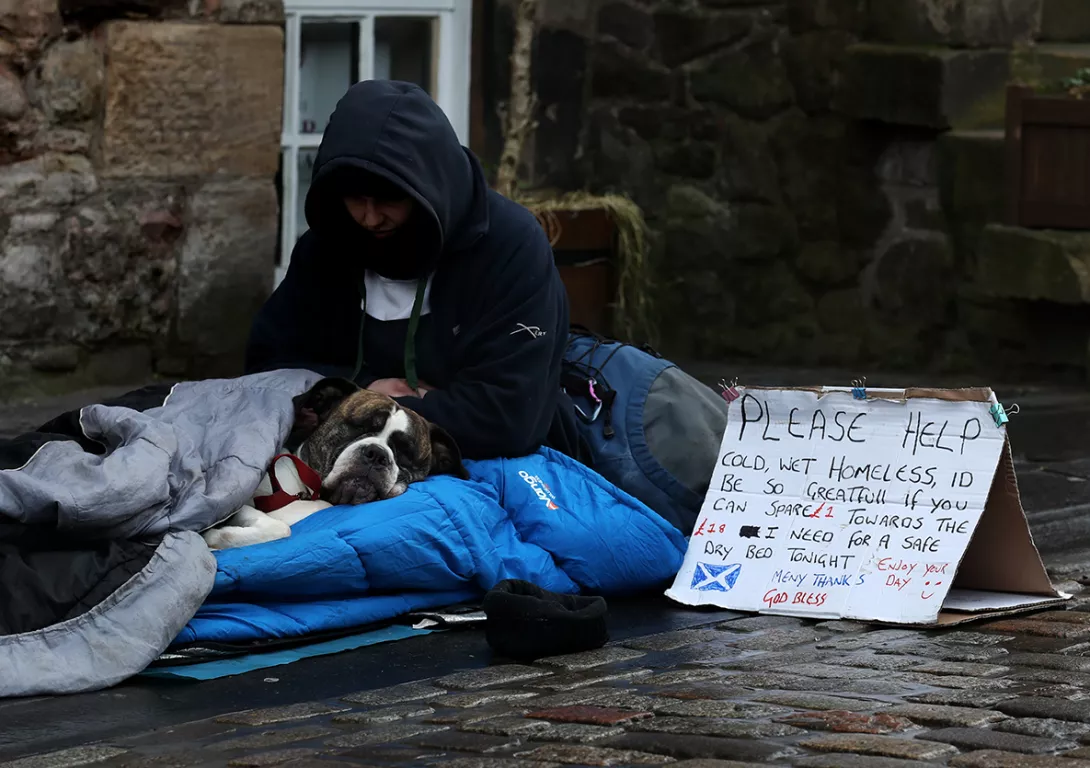

In Caledonian Road, big thumper of a novel at over 600 pages, Scottish writer Andrew O’Hagan offers a post-Brexit, liberalist mea culpa of sorts, repositioning Britain in its isolated decline.

O’Hagan’s focus is a London “levitating on a sea of dirty money,” as Sergei Magnitsky put it. Emerging from the pandemic in 2020, the masks are coming off and there’s profit to be extracted.

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

TIM DAWSON looks at how obsessive police surveillance of journalists undermines the very essence of democracy