GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

Winning hearts and minds

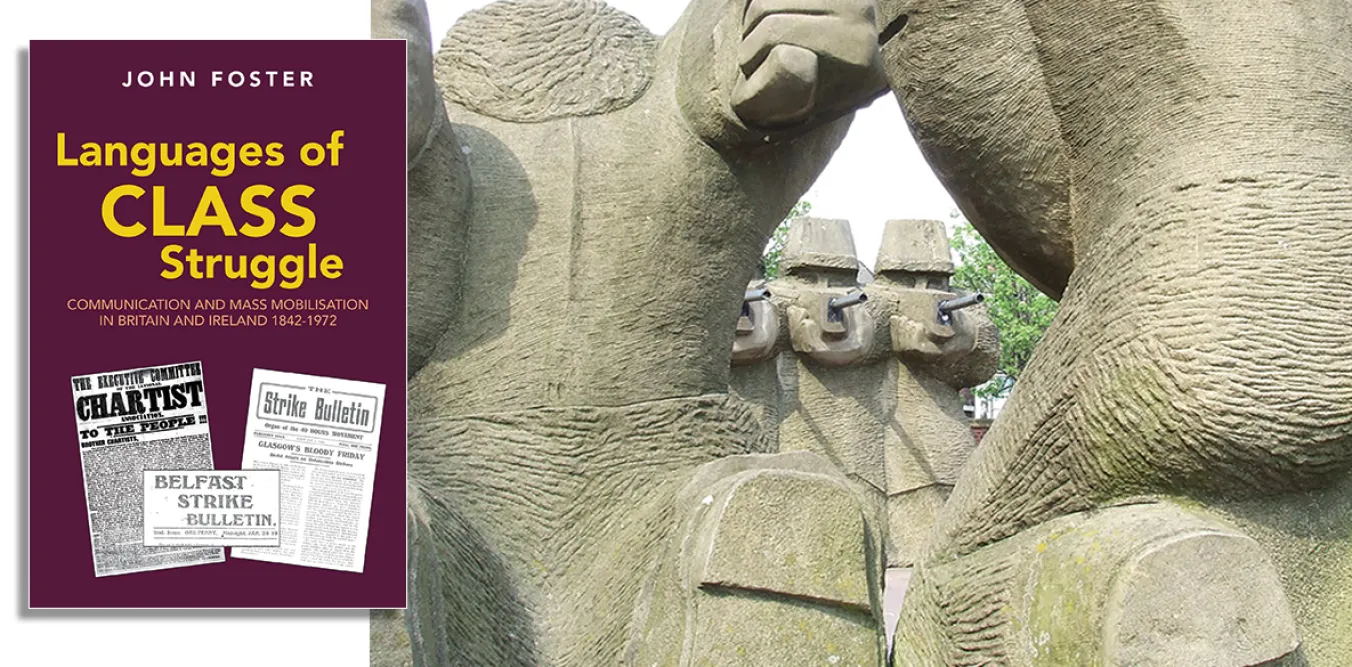

JONATHAN WHITE recommends a key study that shows how language is vital to the mobilisation of the class and the development of consciousness

Languages of Class Struggle: Communication and Mass Mobilisation in Britain and Ireland 1842-1972

John Foster (Praxis Press, £25)

IN 1847, Karl Marx wrote that in the process of struggle the working class is transformed from being a class against capital into a class “for itself,” consciously struggling to change the social order.

Throughout his career, from his ground-breaking book Class Struggle and the Industrial Revolution onwards, John Foster’s work can be seen as a dialogue with this idea.

What are the concrete conditions in which class consciousness can develop? Exactly how do classes mobilise and reach the point where they start to pose a challenge to state power? How does consciousness change in the process of struggle and what role do leaders play in this process? What is left over when mobilisations end?

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

RICHARD MURGATROYD is disappointed by an ambitious survey that fails to get to grips with the relationship between human consciousness and nature

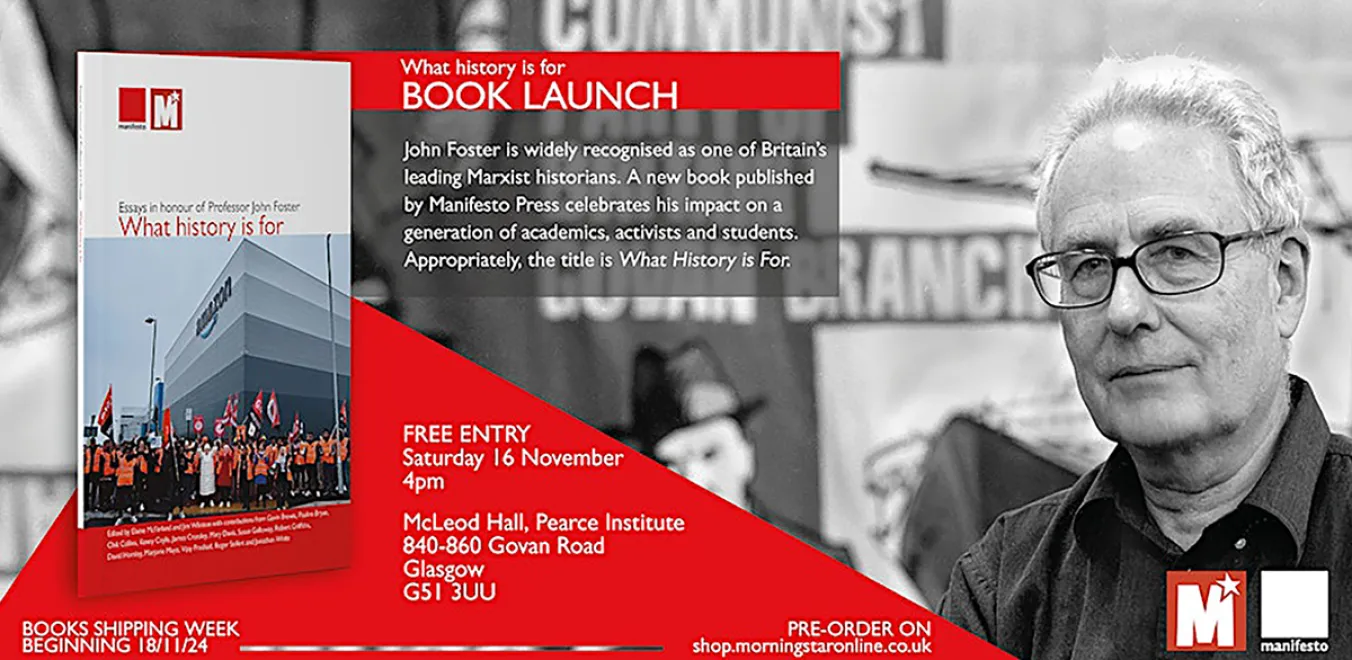

ELAINE MCFARLAND and JIM WHISTON introduce a collection of essays published in honour of Professor John Foster

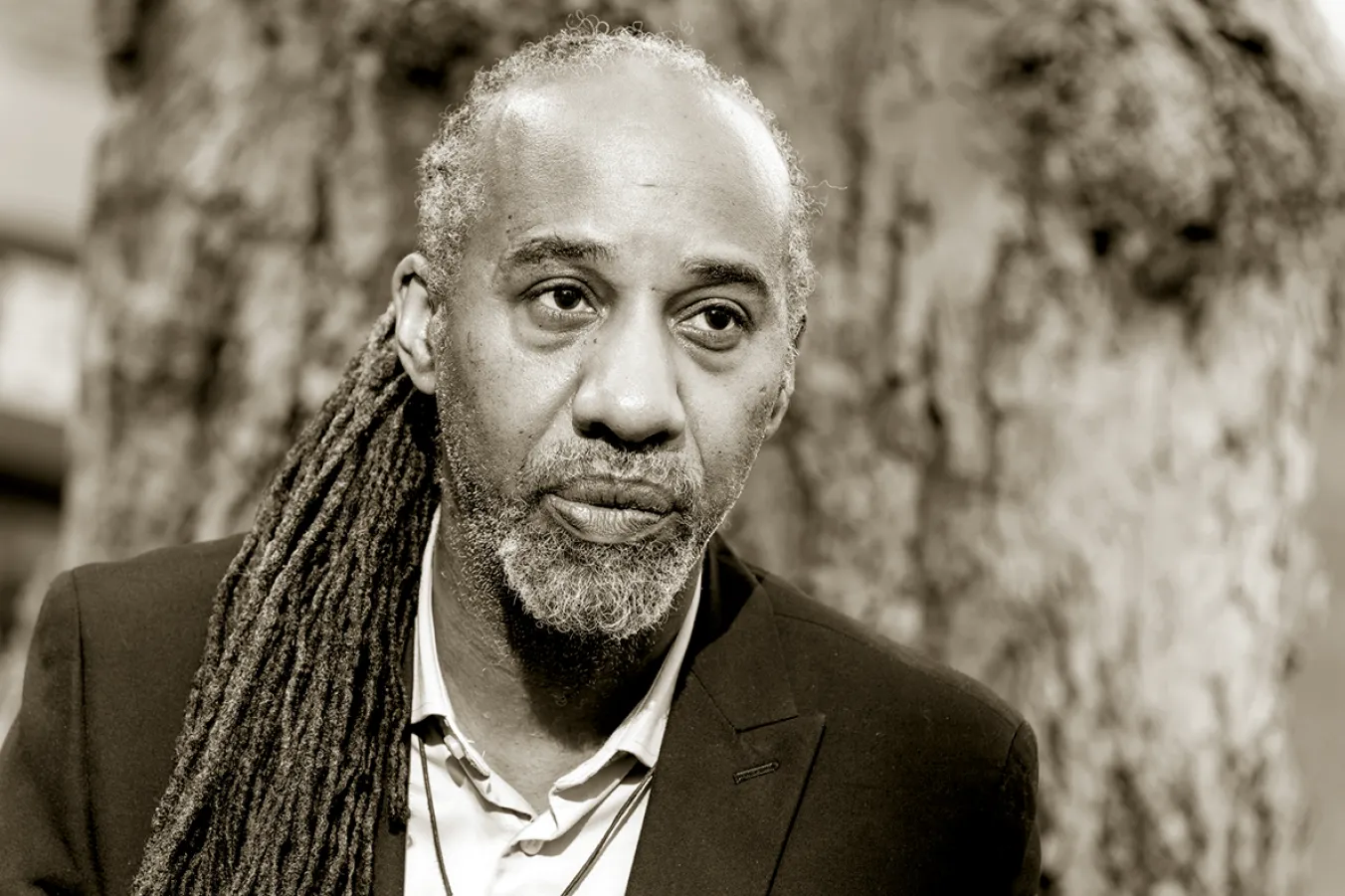

Ben Chacko talks to TYEHIMBA NOSAKHERE, co-author of a new GMB-produced book about the incredible stories of trailblazers for racial equality

For many Labour Party members, deciding whether to leave or stay will turn on the quality and politics of their local councillors and MP, writes the MARX MEMORIAL LIBRARY