ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes two exhibitions that blur the boundaries between art and community engagement

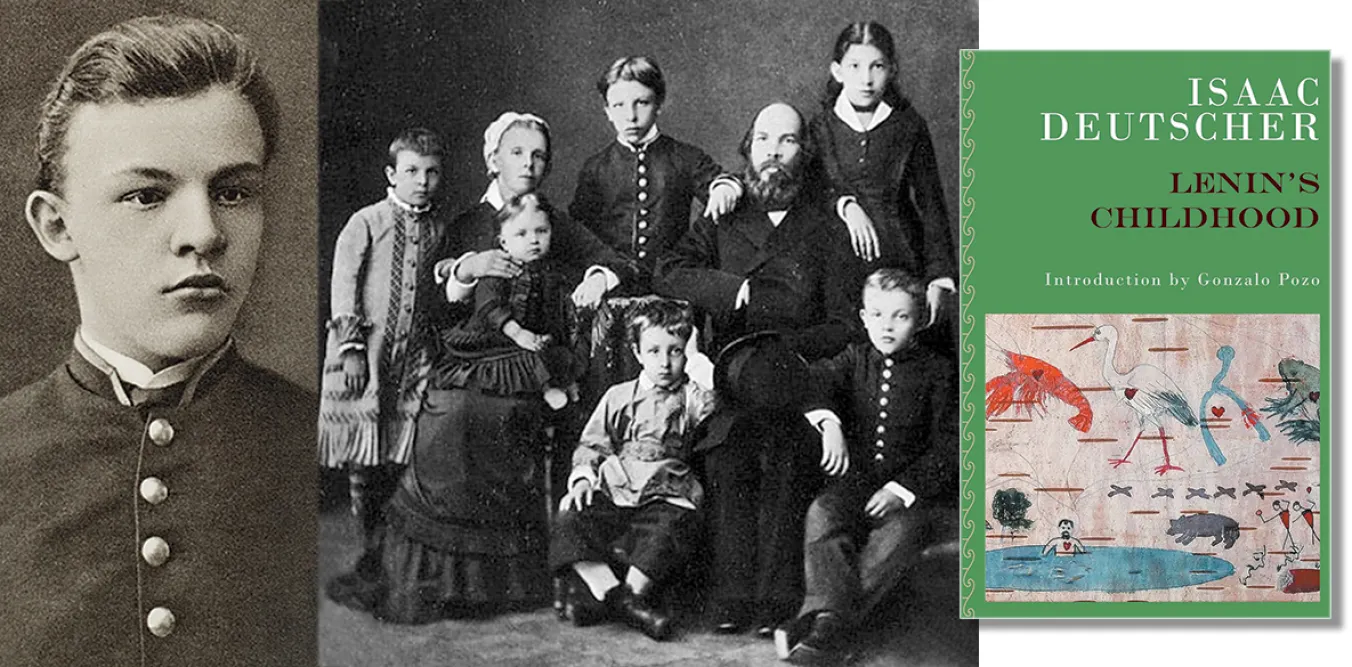

The formative years of a revolutionary

STEVE ANDREW relishes a history of Lenin’s childhood and adolescence that gives a useful insight his personality

Lenin’s childhood

Isaac Deutscher

Verso, £10.99

POLISH Marxist Isaac Deutscher is best known for having penned monumental biographies of Bolshevik leaders Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky, the latter running into some three huge volumes.

Whether or not the reader may agree with the perspectives contained therein, no-one could ever doubt Deutscher’s majestic writing style and his lifelong ability for research that was both meticulous and groundbreaking.

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

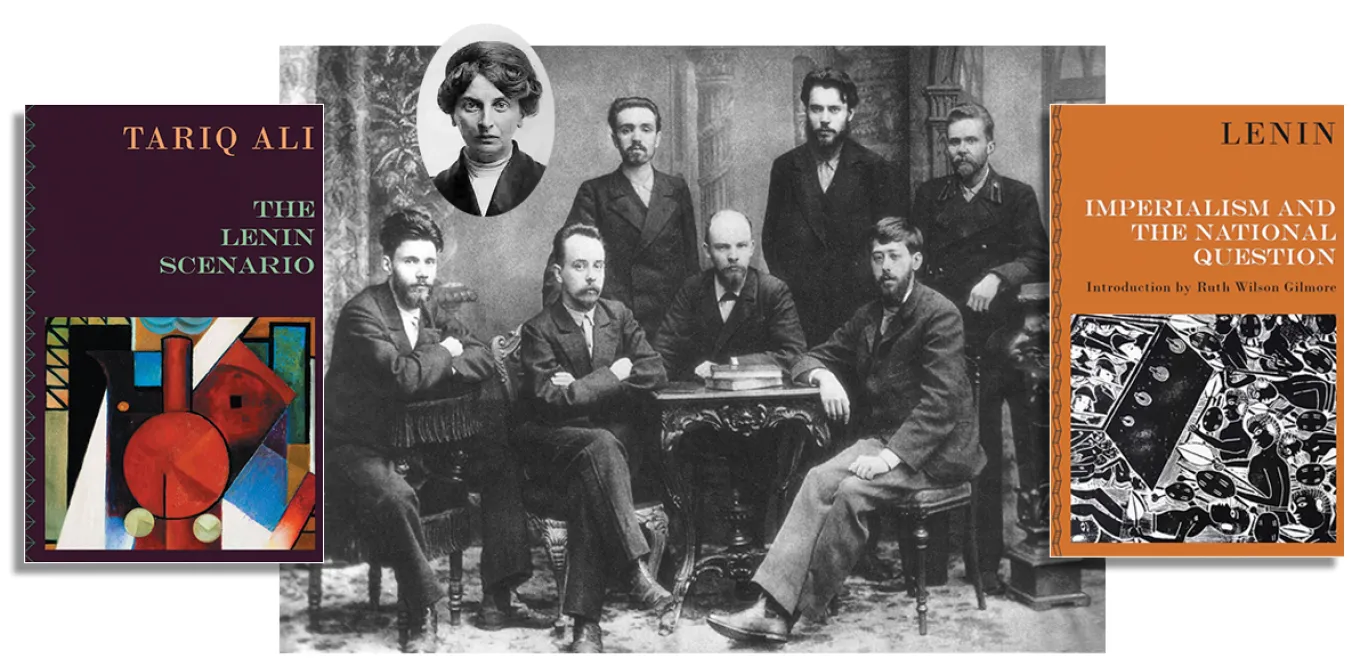

GAVIN O’TOOLE applauds a uniquely nuanced people’s history of the revolutionary period, told from below

ANDREW MURRAY recommends two titles that popularise Lenin as a person and revolutionary theoretician and practitioner

PAUL BUHLE adds historical context to an eclectic and colourful celebration of Lenin

NICK MATTHEWS looks at the great Bolshevik leader’s intense three-week period of furious study in the British Library in 1908 and the timeless classic on Marxism and philosophy it produced: Materialism and Empirio-Criticism