The proxy war in Ukraine is heading to a denouement with the US and Russia dividing the spoils while the European powers stand bewildered by events they have been wilfully blind to, says KEVIN OVENDEN

Britain is going hungry

Growing food poverty is among the realities of Tory Britain — radical solutions are needed, argues CHRIS STEPHENS MP

THE politics of food is essential. But, unfortunately, it is not stated often enough, nor the struggle of those who suffer from food insecurity, nor its causes.

Yet, food insecurity reflects the broken social security and immigration systems we have in Britain.

A recent visit to a Summer Lunch Club provided an illustrative example.

More from this author

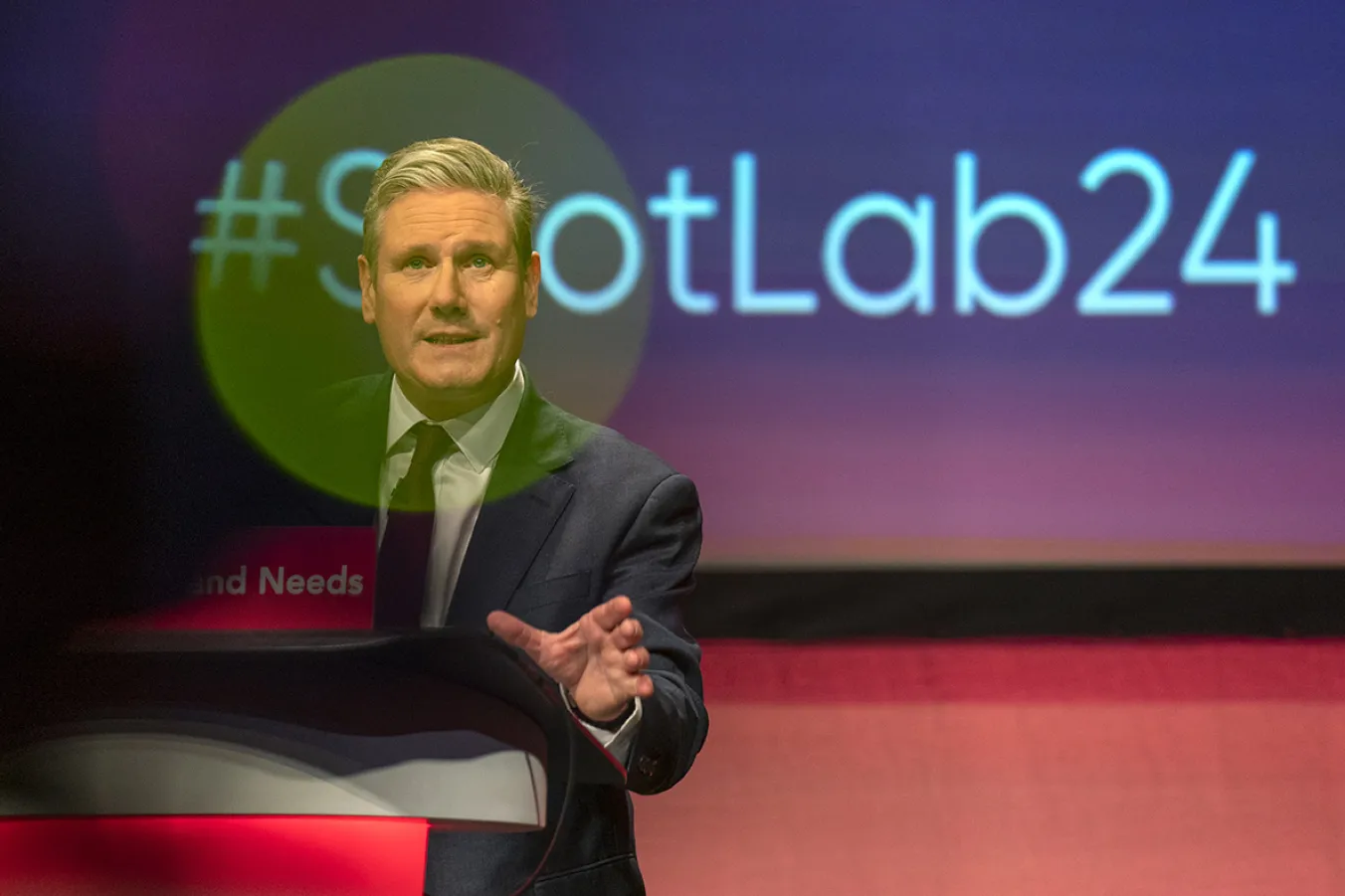

After Keir Starmer has made his politics plain for all to see, CHRIS STEPHENS MP argues that the SNP is now the more progressive party on the NHS, geopolitics, nuclear weapons and workers’ rights

Only by stating the case for the SNP to remain a progressive party of economic and social reform that will lead us to full independence from Westminster will we remain in power — one candidate does that, argues CHRIS STEPHENS MP

In the face of Tory machinations under the guise of a 'review,' the Scottish government and trade unions are opposing any downgrading of our employment protections, reports CHRIS STEPHENS MP

There is something sinister about Boris Johnson's whipping up fear of Scottish involvement in Westminster, writes CHRIS STEPHENS

Similar stories

We need a ‘right to food’ enshrined in law and universal free school meals, as 7.2 million households face food insecurity after years of devastating failed Tory policies, writes ANNETTE MANSELL-GREEN

Millions are going hungry in our nation, but Labour is still not prepared to commit to taking the action needed to address the chaos the Tories leave in their wake, write Dr TOMMY KANE, ALEX COLAS and Dr MICHAEL CALDERBANK

Dire times ahead as the collective energy debt in the UK now amounts to £3.1 billion, writes KENNY MACASKILL