Speakers in Berlin traced how Germany’s rearmament, US-led violence abroad and the repression of solidarity at home are converging in a dangerous drive toward war. BEN CHACKO reports

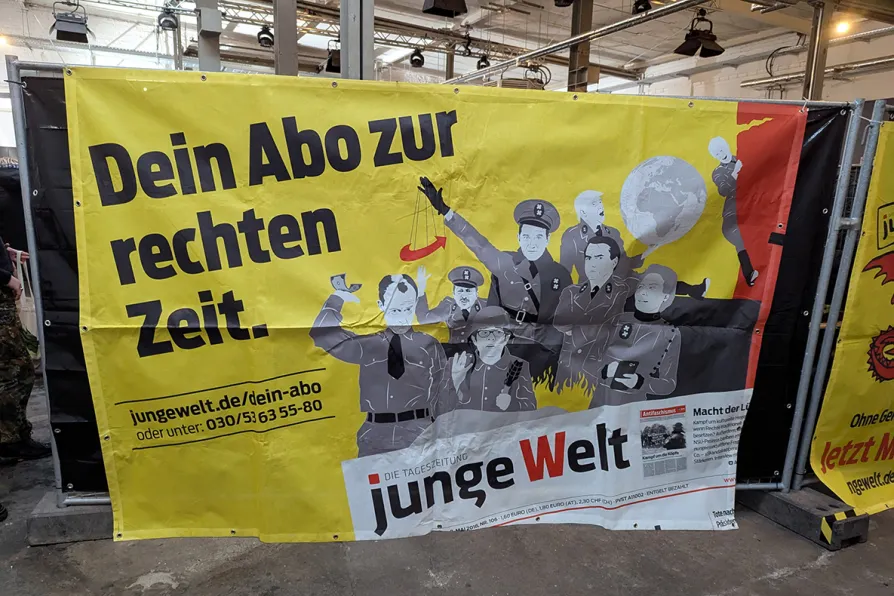

“HEAD over heels into war” was the theme of this year’s Rosa Luxemburg Conference in Berlin, organised as ever by the Morning Star’s German sister paper Junge Welt.

And the voices of school strikers, trade unionists, human rights activists, economists and socialist campaigners throughout the day left no doubt that this is the trajectory of Germany and the whole of Europe.

The shadows of genocide in Gaza and the shredding of international law through US boat bombings, piracy at sea and the kidnap of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro loomed over the thousands who came to discuss how to stop a world war that looks ever closer.

The crisis in the Caribbean prevented Emilio Lozada — head of international relations for the Communist Party of Cuba — from attending as planned, but Manuel Pineda of the Communist Party of Spain struck an urgent note on solidarity with the socialist island.

“Cuba is in danger,” he warned. “Trump is a fascist. He is a danger to humanity as a whole — and he wants Cuba to collapse. Cuba is being strangled.”

Already reeling under the impact of a 64-year blockade — “the most extensive, complex and long-lasting sanctions regime in history,” which made everything from stocking shop shelves to running buses a constant struggle, the US’s increasing readiness to simply steal supplies headed for Cuba, as it did with a Venezuelan tanker shipping oil to the island last month, represents an existential threat.

“Cuba has shown us what solidarity is,” he said, speaking of the medical brigades sent to crisis points across the world — including Europe during the pandemic.

“Now we need to show solidarity with Cuba. That can’t just mean wearing a T-shirt. It needs finance, investment, we need to organise support for Cuba in communities, via pressure on local governments, mayors,” he urged.

That need for practical solidarity — marching, fundraising, organising to affect policy — was the key theme in UN special rapporteur Francesca Albanese’s address on the crisis in Gaza too. The German government was among Israel’s closest allies, she said, maintaining military and diplomatic support and severely repressing Palestine solidarity activism — yet polls showed despite it all the German people are in their majority with the Palestinians.

Violence and instability radiate, above all, from the United States. Abolitionist Law Centre director Robert Holbrook — in a discussion as to whether the most powerful state on Earth is now on the brink of civil war — declared that “the American empire is dying. The facade of legitimacy is gone … the American people are realising that they live in a failed state.”

There was no consensus though on who was responsible for its decline, hence the considerable support for Donald Trump’s ever more extremist Maga movement.

“Trump is deliberately dividing the American people… rewriting the rules of the post-World War II international order. Domestically and internationally the order is being reset — it brings chaos, but it also brings opportunity.

“The transparency of Trump’s plunder is developing an emerging class consciousness, transcending race and ethnicity in the United States.

“The Democratic party has shown itself incapable of stopping fascism in the United States or genocide in Gaza. In many cases it collaborates. People are waking up to the fact that a new politics is necessary — socialism is no longer a bogeyman.”

Just as the Democrats cannot stand up to Trump, internationally Europe is proving an accomplice to the US war drive rather than some kind of liberal check on it.

And western Europe’s largest, richest state, Germany, has — in the words of Boris Pistorius, the belligerent Defence Minister who moved seamlessly from the Social Democrat (SPD) led Olaf Scholz administration to the Christian Democrat-led Friedrich Merz one, not even moving seats round the Cabinet table — set itself the task of being the “pacemaker” in this process.

“To overcome stagnation, Germany seeks to put its economic and political leadership of Europe on a new, military footing,” economist Jorg Goldberg argued.

“Thanks to Trump and other things” the world was moving towards “a generally higher level of violence … threats, thefts, kidnapping and murder are now primary weapons of international relations and even small and medium powers are using violence to assert their interests …

“In a world where violence is more general, military power is the main way to exercise influence,” he said.

Germany had long accepted a lower military status than the smaller economies of Britain or France, both because of the particular horrors associated with its military history and because it could act for its ruling-class interest by leveraging its economic might and the institutions of the European Union.

But now, militarism is “the core of Germany’s economic and political strategy.”

This in a state which recently had to dissolve its commando force the KSK — Germany’s version of the SAS — just a few years ago when the pervasive influence of hardcore Nazis in its ranks was exposed. Another scandal involving officers performing Hitler salutes and donning old Nazi uniforms is currently engulfing its 26th Parachute Regiment.

It would be a mistake to imagine the cheerleaders of German rearmament are uniformly committed to defending “Western democracy” — as the late Victor Grossman memorably put it to me at a previous Rosa Luxemburg Conference, with many of them “you can smell Hitler.”

Germany has announced a €500 billion fund for military readiness. It has changed its constitution, which limits public spending, to exempt military spending from the rules.

It aims to increase the Bundeswehr from 180,000 to 260,000 troops, to which end it has passed a new law obliging all men to register with the military and undergo medicals when they turn 18; actual military service remains voluntary, but the law states that it may become compulsory if the required number of volunteers cannot be found (which present polling suggests they won’t be).

Preparation for war — the nightmare drumbeat sounded by British top brass saying our “sons and daughters” must be ready to fight, by France’s most senior general saying it must “sacrifice its children,” by Nato secretary-general Mark Rutte’s warning we must prepare for a war “on the scale our grandparents and great-grandparents faced” — is the order of the day in Germany too.

Nadja Rakowitz of the Association of Democratic Physicians said that even as German hospitals are being closed, new, underground military hospitals are being commissioned; states and cities are developing plans to cope with war casualties, subordinating civilian to military healthcare, as in Berlin’s Framework Plan for Military and Civilian Co-operation.

When politicians talk like this, she advised, we should remember that “it will be the children of the working class on the front line. Not the children of doctors, and certainly not the children of capitalists and politicians.”

This class consciousness ran through the key sessions on how to organise against war — both the youth panel against conscription, hearing from organisers of last month’s 55,000-strong school strikes, and the lively culminating session on Butter Not Guns.

This included the only SPD MP to have voted against the constitutional amendment for unlimited military spending, Jan Dieren, and Die Linke MP Ulrich Thoden; sharp (and to a British observer familiar) divisions over these parties’ approaches, indeed whether it is even possible to effectively campaign against war from within the SPD, were aired from the platform and the floor.

Dieren stressed that ordinary SPD members were not nearly so warlike as the party’s MPs; Thoden, in the face of sharp criticism of “parliamentarism,” that the key was mass external pressure on MPs from below: “if there is no pressure from the streets it’s only the curtains that move in parliament.”

Another difference of opinion emerged on whether a rising global South was a force for peace. Communist Party (DKP) speaker Tatjana Sambale said the demonisation of China and Russia was part of the war drive, and noted that Trump’s aggression in Latin America was premised on its countries’ developing Chinese ties: “We have to say who’s to blame. We stand with Cuba and Venezuela.”

Yusuf As of the Federation of Democratic Workers’ Organisations, which organises among mainly Turkish and Kurdish immigrant communities, disagreed while acknowledging that globally “the main aggressor is the United States.” Similar differences exist within the British anti-war movement and should not be allowed to hinder unity of action against militarism and war.

And action remained the focus of the 31st Rosa Luxemburg Conference.

Plans for a human chain around the Munich Security Conference next month were detailed, the audience asked to contact organisers and travel to the Bavarian capital if they can.

Young people vowed still bigger school strikes against conscription to take place on March 5, and explained tactics for mobilising youth from anti-war sports clubs to school debates and referendums. A Ver.di union activist explained how the union had been won to pledging legal support and advice for any members who get called up and want to resist the process.

A sobering day, in which the appalling reality of the continent’s headlong rush to war was made terrifyingly clear: but an uplifting one too, given the audience (including many hundreds of young people) was engaged in unapologetic opposition to German rearmament, conscription and solidarity with Palestine, Cuba and Venezuela.

Conversations of this kind, sharing experiences of how to organise, need to happen across Europe. The International Meeting Against War on June 20 in London will be a big opportunity for that over here. Trump’s aggression grows more brazen by the day; it has to be stopped.

Ben Chacko is editor of the Morning Star.