GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends an important, if dispiriting book about the neo-colonial culture of Uganda under Yoweri Museveni

By telling the story of a lawless frontier town from the point of view of the Lakota, Chinese labourers, prostitutes and displaced prospectors, makes for a potted history of capital, suggests ALEX HALL

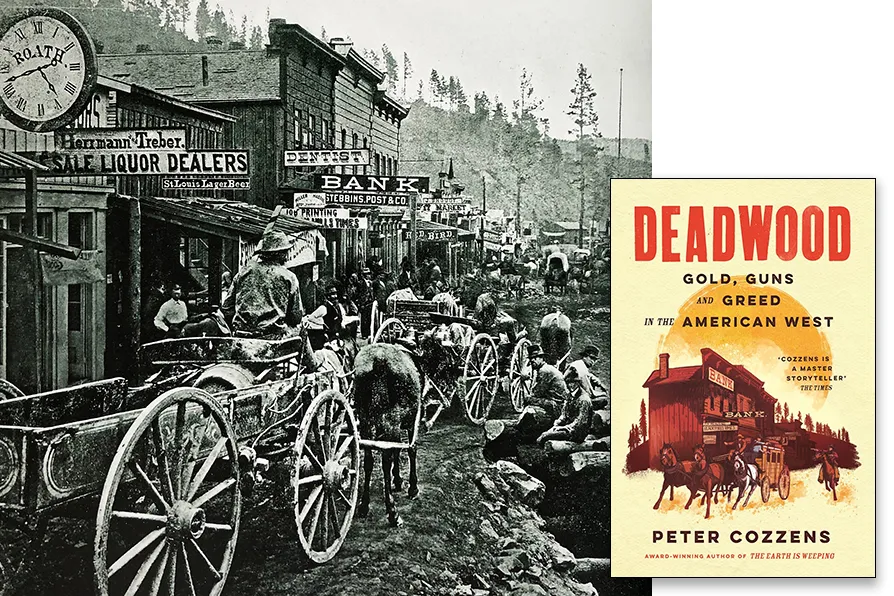

INTENSE CAPITALIST HEYDAY: Deadwood (South Dakota) 1876 [PIc: Public Domain]

INTENSE CAPITALIST HEYDAY: Deadwood (South Dakota) 1876 [PIc: Public Domain]

Deadwood: Gold, Guns and Greed in the American West

Peter Cozzens, Atlantic Books, £25

THE HBO series Deadwood masterfully dramatised the birth of a lawless gold-rush town, blending real historical figures with writer David Milch’s creative licence. In his new history, Peter Cozzens returns to the original newspaper archives to separate myth from reality. The result is an account that does more than fact-check a television show; it adds additional contexts and viewpoints.

What neither Milch, nor Cozzens explicitly draw out is that the history of Deadwood is the history of capitalism, in a furiously fast microcosm. But read this book, or indeed watch the TV series, in this light and it readily becomes apparent.

The development of the United States was of deep interest to Marx. The US was a crucial arena where the contradictions and possibilities of capitalism were playing out in real time, and Deadwood would go through key economic stages in three years.

The story begins with a profound illegality. Following George Armstrong Custer’s 1874 expedition, which declared gold in the Black Hills, a rush began on land guaranteed “in perpetuity” to the Lakota by treaty. The miners’ invasion was a pure act of settler-colonialism, what Marx might have termed “primitive accumulation”: the seizure of land and resources that provided the initial fuel for capitalist expansion. The Lakota, as leader Black Elk noted, saw little value in the “yellow metal,” but its promise to the early US rendered treaties meaningless.

What Cozzens charts next is the rapid, violent evolution of a full economic ecosystem. The initial prospectors were quickly surrounded by those who would profit from their labour and dreams: merchants, gamblers, saloon keepers, prostitutes and con-men. Establishments like Al Swearingen’s Gem Theatre would take on average $5,000 a night, a staggering sum. These early capitalists however still required some trappings of protection, ie justice. Cozzens shows how rudimentary “miners’ courts” provided a semblance of order where formal law was absent, and how later “legitimate” order was provided.

This chaotic, entrepreneurial phase was intensely brief. Once viable claims were proven, industrial capital arrived personified by George Hearst. Hearst systematically monopolised the major claims, introducing hydraulic mining technology that increased yield but also ravaged the environment. This shift from individual diggers to corporate extraction marks a classic capitalist transition, consolidating wealth and power while displacing the original risk-takers.

Cozzens’ work is particularly commendable for expanding the narrative beyond the iconic gunfighters and tycoons. He documents Deadwood’s sizeable Chinese community, which formed a distinct Chinatown which was to some extent integrated with the European settler town. He notes that for many black Americans, the frontier offered a precarious but preferable alternative to the oppressive South. Most significantly, he provides a clear-eyed account of the Lakota’s devastation, framing their displacement not as a backdrop but as the central injustice that enabled the entire enterprise.

The town’s physical decay mirrored its economic consolidation. The devastating fire of 1879, which destroyed much of Deadwood, served as a symbolic end point. With the easy gold gone and controlled by large interests, the small miners, their entertainers, parasites and suppliers moved on to the next boom town: Leadville, Colorado. The intense capitalist “heyday,” as Cozzens observes, lasted barely three years.

Cozzens does not entirely dispel the potent mythology of the rugged, entrepreneurial West that Deadwood helped forge. Instead, he elucidates the true cost of that mythology. By examining the town from the perspectives of the Lakota, Chinese labourers, prostitutes and displaced prospectors, he provides an essential multi-sided view.

This history reveals Deadwood not merely as a lawless adventure, but as a stark, rapid and instructive parable of how US capitalism was built: through appropriation, violence, fleeting opportunity, parasitism and the ultimate triumph of concentrated capital.

Deadwood is now a tourist town, its raw history polished into a commodity for sale.