Hundreds protested against the US-Israel attacks on Iran in Parliament Square on Saturday, fearing a wider conflagration and horrified by the targeting of young schoolchildren, writes LINDA PENTZ GUNTER

1943-2025: How one man’s unfinished work reveals the lethal lie of ‘colour-blind’ medicine

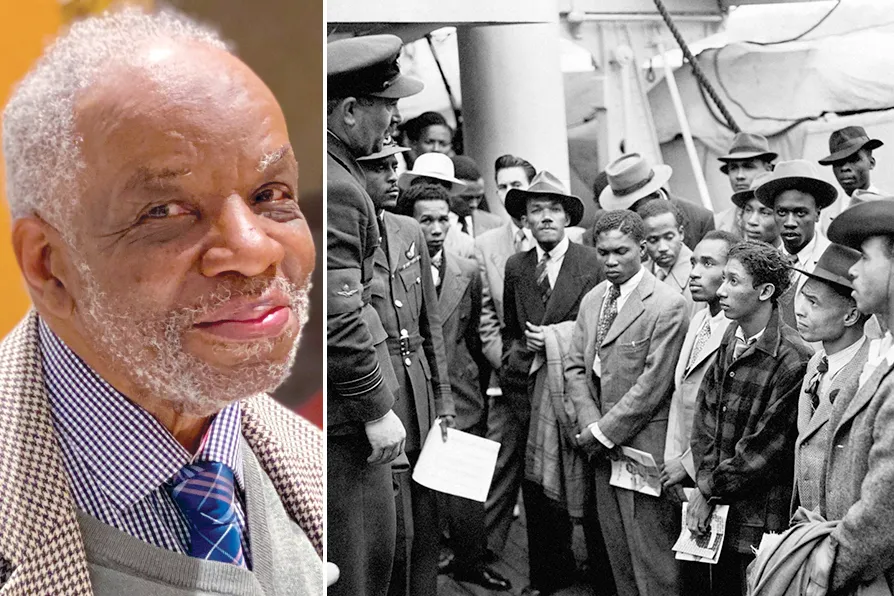

TRAILBLAZING RESEARCH: Dr Aggrey Burke in 2022; Jamaican immigrants met by the Colonial Office officials as they disembark from the Empire Windrush [Pic: Whispyhistory/CC]

TRAILBLAZING RESEARCH: Dr Aggrey Burke in 2022; Jamaican immigrants met by the Colonial Office officials as they disembark from the Empire Windrush [Pic: Whispyhistory/CC]

ON SUNDAY December 21 2025, Dr Aggrey Washington Burke died at the age of 82. The medical establishment released measured tributes. Colleagues spoke of his “contributions.” Papers will be written in academic journals. But none of these words — not “pioneer,” not “trailblazer,” not even “revolutionary” — adequately capture what Dr Burke spent four decades proving: that medicine, in the hands of an empire, becomes a weapon of control. That healthcare is not neutral. And that those who benefit from racism will kill to protect it.

Burke was not celebrated during his lifetime. Instead, he remained what one contemporary described him: a quiet revolutionary, operating in the margins, speaking scientific truth to institutional power, and building intellectual frameworks that shattered the comfort of a medical establishment determined to deny the obvious: that structural racism damages health. That it kills. That it is a choice.

Burke advised and inspired me from my early days throughout my working life, starting with my role as a principal training officer delivering the Home Office Joint Investigation of Child Sexual Abuse training in Nottinghamshire, through to my time as a community activist, and working with the first mayor of London at City Hall, and continuing throughout my career as a politician, both as an elected councillor and a member of Parliament. He was a guiding spirit and strength throughout. His last words to me, and we generally caught up at least once a year, were, “be strong and continue your good work.”

In the early 1960s, Aggrey Burke worked at Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital in Jamaica. He turned his attention to a phenomenon that should have been shocking but was instead made invisible: repatriates — Jamaicans who had emigrated to Britain seeking opportunity, only to meet systematic exclusion and contempt — were dying by suicide at catastrophic rates. One in four.

This was not psychiatric illness in the traditional sense. This was a nation’s hatred, internalised, becoming a lethal force. A man’s identity valued at zero in the eyes of the empire he had travelled to serve. A woman’s labour extracted while her humanity was denied. This was the architecture of imperialism working in real time, destroying minds and bodies with methodical precision.

Burke’s work in Jamaica revealed what should have been obvious but what the British medical establishment would spend decades denying: racism doesn’t simply offend. It kills. It operates as an engine of psychological harm, with measurable, lethal consequences.

When Burke himself arrived in Britain in 1959 to complete his psychiatric training, he entered a healthcare system that had not yet produced a single black consultant psychiatrist. The system had a reason for this. It was working as designed.

In the late 1970s, Burke became the first black consultant psychiatrist appointed by the NHS — a breakthrough secured through struggle, against an institution designed to exclude him.

Once inside, Burke did something that few do, he refused to assimilate. He refused to accept the institution’s self-image as rational and fair. Instead, he used his position to expose what was happening inside Britain’s supposedly “colour-blind” healthcare system.

In 1976, Burke published rigorous epidemiological research examining attempted suicide rates across Irish, “West Indian,” and Asian communities in Birmingham. The disparities were stark. They could not be explained away by poverty alone. They could not be reduced to “cultural factors,” though culture was weaponised against non-white patients. They pointed directly to the reality: the British medical system was structured to harm black and Asian people.

Today, in 2025, the NHS’s own data confirms what Burke proved 50 years ago: black people are detained under the Mental Health Act at 262.4 per 100,000, compared to 65.8 for white people. That is four times the rate, and the gap is widening. Black people are less likely to receive mental health support when they first struggle, more likely to reach crisis point, and then disproportionately detained without therapeutic intervention that could prevent incarceration. This is not accident. This is system.

The evidence now shows what Burke understood intuitively: structural racism damages health through direct physiological pathways and indirectly through enforced poverty, residential segregation, environmental toxins and carceral violence. A 2025 scoping review of 83 peer-reviewed studies confirmed this mechanism operates across healthcare, housing, criminal justice and environmental systems. It is architecture. It is deliberate. And it is profitable.

The cost? Between 1999 and 2020, structural racism caused 1.63 million excess deaths among black Americans alone — an average of 74,090 black lives lost every single year that would not have been lost if racial health inequities were eliminated. The figure for Britain remains undocumented, a silence that is itself an act of violence.

The new cross fire and the politics of trauma

On January 18 1981, a house in New Cross, south London, burned. Thirteen young black people — most of them teenagers — were murdered. Their names were Andrew Gooding, Rosaline Henry, Patrick Cummings, Patricia Johnson, Owen Thompson, Lloyd Hall, Humphrey Brown, Steve Collins, Gerry Francis, Peter Campbell, Glenton Powell, Yvonne Ruddock and Paul Ruddock. The community knew immediately what had happened. The police response was indifference bordering on contempt.

In the years following, Burke took on therapeutic work with the bereaved families. He was not there as a clinician dispensing medication to manage their grief. He was there as a witness to a nation’s failure, as someone who understood that healing from trauma requires justice, not pills. That mental health is inseparable from political struggle.

This was Burke’s insight: the task of a radical psychiatrist is not to adapt people to oppression. It is to name oppression. To prove it. To make liberation thinkable.

In 1986, Burke co-authored a paper in the journal Medical Education with Dr Joe Collier that provided the first rigorous evidence of systematic racial and sexual discrimination in medical school admissions at London colleges. The paper was not theoretical. It was backed by data. It named the institutions. And it forced a response: a Commission for Racial Equality inquiry in 1988 that resulted in actual structural changes.

Burke had done something that few in power dare to do: he had wielded evidence to force institutional change. The medical establishment had no response but to capitulate, at least in form if not in substance.

But Burke understood something that few psychiatrists grasp: that mental illness cannot be separated from global systems of power. That the psychiatric crisis in the global North is connected to the extraction of resources and life from the global South. That health inequality is imperialism.

In 2025, the evidence is overwhelming. Africa imports between 70-90 per cent of its finished pharmaceuticals and manufactures less than 1 per cent of the vaccines administered on the continent. This is the direct legacy of colonial extraction, intensified by structural adjustment policies of the 1980s-90s that dismantled state-owned pharmaceutical capacity, and cemented by intellectual property regimes — particularly the TRIPS Agreement (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) — that lock critical knowledge behind patents controlled by global North corporations.

African nations cannot manufacture their own medicines. They cannot develop locally relevant healthcare research. They remain dependent on the global North for survival — a dependence that extracts wealth, maintains poverty and perpetuates the health inequalities that kill millions annually.

This is what Burke knew: health is not technical. Health is political. And inequality is a choice made by those in power.

The violence that Burke exposed came from systems with names. The British government continues to structure the NHS in ways that disproportionately harm black people. Medical education resists genuine decolonisation despite reforms. The global North pharmaceutical industry restricts technology transfer to Africa, prioritising profit over lives. Intellectual property regimes lock the global South out of the knowledge required for health sovereignty.

Britain’s “New Approach to Africa,” announced in June 2025, frames engagement as “partnership” and “mutual respect.” But it is dressed-up neocolonialism — soft power dressed in the language of development. The same relationship of extraction and control, recycled through new language.

Burke’s life and work point toward solutions that are not rhetorical but structural. Not charity but justice. Not “diversity” within oppressive systems but the dismantling of those systems themselves.

Pharmaceutical sovereignty in Africa is not a luxury. It is a prerequisite for decolonisation. This requires breaking intellectual property restrictions that lock knowledge in the global North; technology transfer agreements that empower African research and manufacturing; concessional finance for pharmaceutical capacity; and procurement reform that rewards African production. It requires treating Africa not as a market to be exploited but as a centre of knowledge and innovation.

Reparations and resource reallocation from the global North to the global South is justice for centuries of extraction, enslavement and colonial plunder. The wealth of the global North was built on the resources and labour of the global South. That relationship continues. It must be reversed.

Decolonisation of global health governance means that African nations, Caribbean nations, and all nations of the global South must control the health research agendas that affect their populations, the regulatory frameworks that determine medicines availability, and the resources that sustain their health systems.

Structural accountability means healthcare institutions held responsible for embedded racism in their structures. Not through “diversity training.” Not through symbolic appointments. But through genuine power redistribution, resource allocation, and governance reform.

An unfinished revolution

Dr Aggrey Burke died on December 21 2025. Beyond his clinical and research work, he was a co-founder of the George Padmore Institute. He was chair of the Transcultural Psychiatry Society, a position from which he shaped intellectual and professional discourse around race, culture and mental health.

Despite all that he achieved, including as a consultant psychiatrist and senior lecturer at St George’s Hospital, Tooting, his work remains incomplete. Black people continue to be detained in psychiatric institutions at four times the rate of white people. Health inequalities between rich and poor nations continue to widen.

Pharmaceutical imperialism kills. And the British healthcare system continues to deny the obvious: that racism is not incidental to medicine. It is embedded in its structures. It shapes every decision about who receives care, who is detained, whose life matters.

But Burke’s legacy stands as a testament to the power of speaking truth to power. His work demonstrates that medicine is not neutral. Healthcare is always political. And the struggle for health justice is inseparable from the struggle for racial justice, for decolonisation, for international solidarity among the oppressed.

The revolution Burke began — to prove that another kind of medicine is possible, that another kind of world is necessary — is ours to complete. It will not be complete until health is understood not as an individual commodity but as a collective right. Until imperialism is dismantled. Until Africa controls its own resources. Until black life is valued equally. Until the global South is free.

This was Dr Aggrey Burke’s vision. This is the world he spent his life fighting for.

Claudia Webbe was previously the member of Parliament for Leicester East (2019-24). You can follow her at www.facebook.com/claudiaforLE and x.com/claudiawebbe.

International solidarity can ensure that Trump and his machine cannot prevail without a level of political and economic cost that he will not want to pay, argues CLAUDIA WEBBE

The catastrophe unfolding in Gaza – where Palestinians are freezing to death in tents – is not a natural disaster but a calculated outcome of Israel’s ongoing blockade, aid restrictions and continued violence, argues CLAUDIA WEBBE

Your Party can become an antidote to Reform UK – but only by rooting itself in communities up and down the country, says CLAUDIA WEBBE

Keir Starmer’s £120 million to Sudan cannot cover the government’s complicity in the RSF genocide or atone for the long shadow of British colonialism and imperialism, writes CLAUDIA WEBBE