GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends an important, if dispiriting book about the neo-colonial culture of Uganda under Yoweri Museveni

FIONA O’CONNOR picks books and films that show defiance in the face of violence and injustice

IT’S a funny old ritual — approaching year’s end generates the reckoning of cultural experiences through previous months. Cultural products become markers of our internal journeys; on the daily Tube commute, book in hand, turning the mundane into something richer, stranger.

In 2025 we read books in the midst of carnage. On our screens we watched a genocide unfolding in real time. As the poet WH Auden wrote:

“About suffering they were never wrong,/ The Old Masters: how well they understood/

Its human position; how it takes place/ While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully/ along.”

A documentary that was seared into my mind is Put Your Soul On Your Hand And Walk. Photojournalist Fatma Hassouna on the streets of her neighbourhood in north Gaza with her camera, “trying to find some life in this death.” Film-maker Sepideh Farsi video-called Fatma from Paris each day, making this film from their conversations and shared images. On April 16, 24-year-old Fatma and nine members of her family were killed by an Israeli air strike on their home as they slept.

Lives that defy: testimonies of resistance became a theme through the year. From Ireland came the beautiful film Blue Road, directed by Sinead O’Shea, celebrating the glamorous, turbulent life of the magnificent Edna O’Brien, showing her immense writerly gifts and steely intelligence in challenging oppression.

Later came another film from Ireland: Testimony, directed by Aoife Kelleher, documenting the campaign to make restitution for the Magdalenes, those Irish women, over 10,000 of them, incarcerated by the Catholic church, with the collusion of the Irish state. Both films were made by phenomenally talented young women.

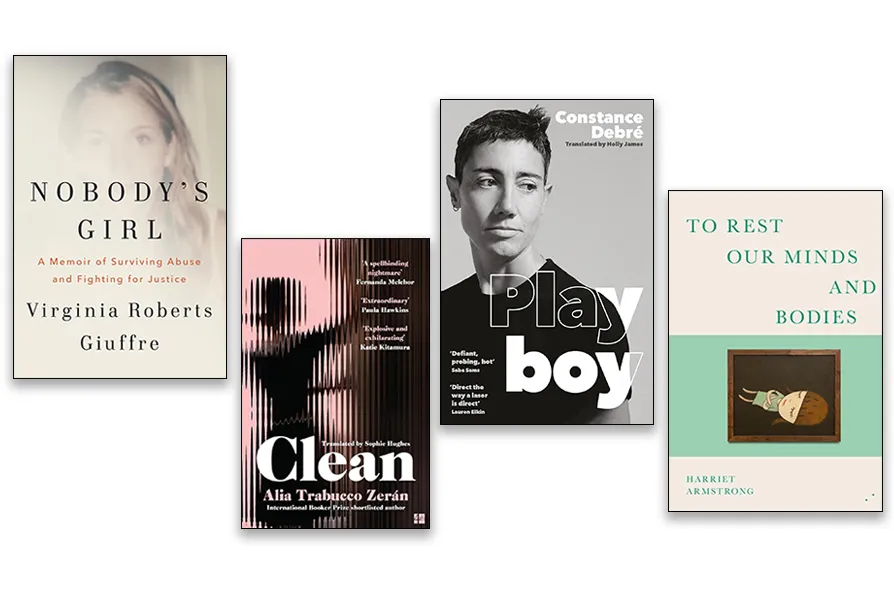

There’s also defiance by the book: Virginia Roberts Giuffre’s memoir, Nobody’s Girl (Doubleday, £25) details an infanthood of neglect and sexual abuse putting her on collision course towards the opulent depravity of Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell. This piece of rhetorical dynamite should be on the school syllabus. In an age where girl-children are spewed out for abuse — by grooming gangs, by tech-driven onslaughts, by lack of government support for girls and women maintaining economic disparity — this book shows the power of truth: how justice can be achieved, no matter the forces against it. But at what a cost to Giuffre herself.

In fiction too, testimonies of resistance were notable. Clean (Fourth Estate, £9.99) by the Chilean writer Alia Trabucco Zeran (translated by Sophie Hughes), captures the drudgery of a live-in maid’s enslavement by a wealthy family, building a sense of dread of impending violent catastrophe that has portents for wider society.

Playboy by Constance Debre (Tuskar Rock, £10.99), translated by Holly James, a coming-out autofiction work shows a 44-year-old woman liberating herself from bourgeois constraints to pursue her attractions to other woman, freely, passionately, ruthlessly. In France, the author’s aristocratic background made it a controversial bestseller. Fascinating in its flipping of male attitudes we consider, or endure, as normative.

An impressive debut novel, To Rest our Minds and Bodies, by Harriet Armstong (Les Fugitives, £14.99), sees a neurodiverse protagonist fearlessly navigate her bewilderment at her body’s sexual awakening and her mind’s emotional upheavals. Another disarmingly honest take on intimate womanhood, in this case from the rare perspective of an autistic protagonist. This is a beautifully written novel by a new British talent.

In a year of depravity-creep, two small books offering space in which to turn away from the raging world: Quite Joyful, by Scots writer Andrew Sclater (Mariscat Press, £9) (full transparency — we once worked together) shares a poet’s vision that combines humour and lyricism with foreboding and grief.

Newly republished from Vintage Classics, In Praise Of Shadows by one of Japan’s greatest novelists, Jun’ichiro Tanizaki (Vintage Classics, £9.99), takes you deep into the soft darkness of traditional Japanese aesthetics. Inhabitation — and even the dimness of a toilet space — is carefully considered: “There one can listen with such a sense of intimacy to the raindrops falling from the eaves and the trees, seeping into the earth as they wash over the base of a stone lantern and freshen the moss from the stepping stones.”

A far cry from the Trumpian garish throne.