Releases from Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Maggie Nicols/Robert Mitchell/Alya Al Sultani, and Gordon Beck Trio and Quintet

JENNY FARRELL relishes an intimate memoir about growing up in the household of the great Irish communist and playwright Sean O’Casey

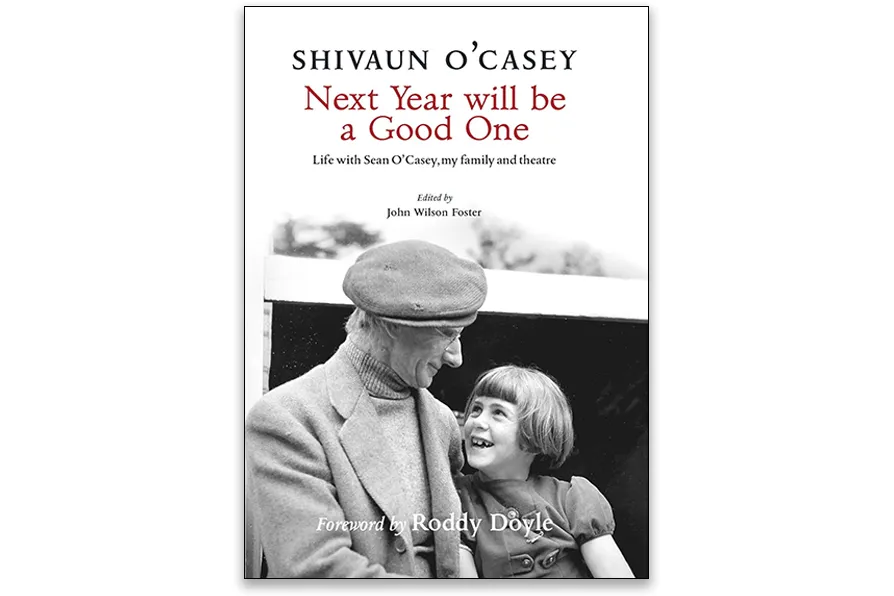

Next Year will be a Good One. Life with Sean O’Casey, my family and theatre

Shivaun O’Casey, Belcouver Press, £20

SHIVAUN O’CASEY, Sean O’Casey’s only daughter and now sole surviving child, has published a remarkable memoir. Born in 1939, she grew up in a very political household: Sean defining himself as a communist for most of his life, his wife Eileen sharing his convictions.

Their home was filled with modernist art, Van Gogh prints, Soviet cinema, the Jooss Ballet, and friends such as Harry Pollitt. Yet ideological richness coexisted with material scarcity, and the solidarity of taking in evacuee children. From the start, the memoir presents politics as lived praxis, embedded in art, education, and survival.

Post-war life brought rationing, the lifting of the blackout, and the grim revelations of the concentration camps, conveyed through friends like Sidney Bernstein. Sean, his eyesight failing, worked nocturnally in a study arranged exactly like his first Dublin room, made pipe-cleaner figures, and sang to Shivaun. Shivaun recalls plucking painful eyelashes from Sean’s eyes and the trove of unpublished letters and drawings that formed part of their domestic world.

The family’s “table cloth was the Daily Worker.”

At GB Shaw’s suggestion, the children attended a progressive, Fabian-linked school, and in one surviving letter Sean wrote to the school: “As a communist, I am in favour of preferential treatment to all in all schools – that is the adapting of educational methods to each child according to its needs.”

The chapter on Purple Dust (1952) reveals both O’Casey’s creative vigour and his precarious professional footing. His rare decision to travel to London and stay with director Sam Wanamaker signalled deep mutual understanding. He contributed new songs to a team including Malcolm Arnold and John Cranko, and entrusted the production to Siobhan McKenna.

The 1955 Gaiety Theatre premiere of The Bishop’s Bonfire became a painful crystallisation of O’Casey’s fraught relationship with Ireland. A first-night riot, likely involving the Legion of Mary, echoed the earlier Plough and the Stars disturbances. More wounding was Gabriel Fallon’s savage critical attack, ending their long friendship and halting plans for a London transfer.

In 1957, tragedy struck when son Niall died suddenly of aggressive leukaemia, leaving the family devastated.

O’Casey’s long conflict with the Irish establishment – from Yeats’s rejection of The Silver Tassie (1928) to the Archbishop McQuaid-driven Tostal Affair of 1958 – defined a career of resistance. Britain posed different barriers: censorship by the Lord Chamberlain and the conservatism of the “Grandees of the Theatre” pushed political works like The Star Turns Red (1940) into left-wing venues such as Unity Theatre.

The Tostal Affair, which forced the withdrawal of The Drums of Father Ned (1959), led to O’Casey’s self-imposed ban on professional productions in Ireland; Samuel Beckett withdrew his work in solidarity.

Shivaun’s US tour revealed the contrast between US admiration for O’Casey and hostility in Ireland. She encountered committed supporters – Brooks Atkinson, Carlotta Monterey, Lucille Lortel – and saw Paul Shyre’s Obie-winning adaptations of O’Casey’s autobiographies and the early development of Juno. Her diary records the brutality of Jim Crow, the poverty of sharecroppers and Native American communities, Klan rallies, and McCarthyism.

Yet, the memoir also maps an internationalist cultural front: Paul Robeson, Charlie Chaplin, blacklisted artists, Soviet publishers, Beckett, Harold Clurman, and Brooks Atkinson – figures linked through shared resistance.

Through Shivaun’s narrative, Sean O’Casey emerges as a persistently relevant revolutionary artist. It illuminates the intersections of communism and culture, and the enduring work of solidarity and resilience.

It is long past time for the English-speaking theatre world to look beyond the familiar Dublin trilogy and restore the full range of O’Casey’s repertoire to the stage, where its breadth, defiance, and contemporary relevance can finally be felt.