SIMON PARSONS applauds an artist who rescues and rehumanises stories of women, the victims of violence, from a feminist perspective

SIAN LEWIS relishes a comprehensive account of high rise social housing in Britain by prize-winning social and political historian Holly Smith

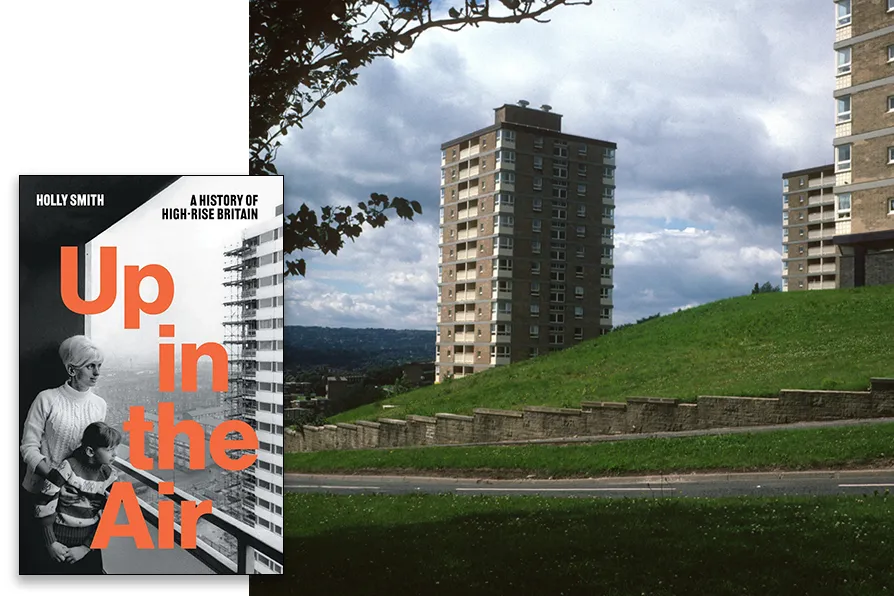

Sheffield City Gleadless Valley, 1987 Pic: Miles Glendinning/CC

Sheffield City Gleadless Valley, 1987 Pic: Miles Glendinning/CC

Up In The Air

Holly Smith, Verso, £12.99

THE book’s black and white cover photo is very clearly a scene from the 1960s — a woman with a distinctive beehive haircut is looking out from her 17th-floor flat, carefully holding a young child as they gaze into the distance.

Vertigo aside, the picture seems a fairly innocuous image of its time until you realise that the scaffolded tower block opposite is not in the process of construction, but being rebuilt.

This is a picture from the recently built Freemasons Estate in London’s Canning Town and the tower across the way is Ronan Point, just a year after its infamous collapse, costing five lives, in 1968. Ingeburg Payne and her family are being evacuated from their flat for strengthening work to begin on the blocks.

In Up in the Air, Smith forensically examines the postwar scramble by councils and developers to build high-density social housing estates as replacement homes for the heavily bombed inner city districts and the slum clearances that had been started before the second world war.

Many of these estates included the high-rise blocks that are the focus of this book. Smith gives us detailed accounts of the attempts of those living in the blocks to fight against the corruption and neglect of cash-strapped councils and self-interested developers, showing us an important history of social housing and 20th-century high-rise living from the often overlooked perspective of the tenants themselves.

After the success of 1951’s Festival of Britain there was a general excitement for all things modern.

Cities especially had a desperate need for new homes and even outside of bomb-damaged areas there was still much substandard housing. Rather than repair existing stock, the decision was usually made to knock down and start from scratch, using modern materials and methods.

There would be bathrooms! Fitted kitchens! Separate bedrooms! Indoor toilets!

It is easy to forget that many less-affluent people did not have access to these things at the beginning of the 1950s.

We see rundown 1960s and 1970s estates now and fail to realise that many people were initially delighted with their new homes. However, as Smith highlights, the cracks soon started to show, often literally.

Developers favoured a new construction method using pre-made concrete slabs that could be assembled on site, by unskilled workers. The Danish Larsen/Nielsen system used for Ronan Point was only ever approved for up to six storeys in Denmark. The 13-storey blocks in Ledbury Estate in Southwark, south London, used the same system — and even recently light could be seen between cracks in the slabs. An inspection of the flats after the Grenfell Tower fire in west London in 2017, in which 72 people died, found that the slabs had not been strengthened after the Ronan Point collapse as they should have been. They are soon to be demolished.

As Smith shows us, the problems with high-rise were more often than not about shoddy construction and lack of maintenance, which in reality means that no-one wanted to spend the money they should have been spending.

This of course has always been the problem with housing provided for the working classes.

However, with the old “age of deference” coming to an end, tenants were starting to organise themselves to fight the “we know what’s best for them” attitude of government departments and paternalistic local councils.

Unfortunately, Smith’s fine examples of tenant organisation and activism ultimately make for depressing reading. Residents who campaigned for their unsafe buildings to be demolished and rebuilt could find the new estate was built with fewer homes and less affordable rents. Many subsequently ended up in bed and breakfast accommodation while waiting to be rehoused or had to move away from their communities.

After the introduction of Right to Buy in 1980, if you successfully demanded that your damp, mouldy, vermin-infested homes were renovated, they might suddenly start to look like desirable real estate, tempting the council to sell them off.

Like the cover image itself, Smith’s writing helps us empathise with the people who lived in those blocks, situated in architect-designed landscapes imposed upon them from above by sometimes well-intentioned but often greedy and unscrupulous individuals and organisations, and the subsequent fights for their opinions to be heard and valued.

Up in the Air is detailed and meticulously researched, yet remains accessible and readable. This is perhaps because the book is ultimately more about ordinary people’s attempts to keep hold of the basic things needed for a decent place to live — and how the greedy few have always found a way to swindle, obfuscate and lie to the detriment of those they care nothing about — than it is about the intricacies and failures of complex engineering systems and changing architectural styles.

It’s an essential read for anyone interested in the rise and demise of social housing and the welfare state in Britain, from the corruption of the early-’70s Poulson scandal and attempts to cover up the cause of the Ronan Point disaster to the policies of successive governments (both Conservative and Labour) up to the present day.

When horrors such as the Grenfell Tower fire can still happen, we know the lessons have not yet been learned.