JENNY MITCHELL, poetry co-editor for the Morning Star, introduces her priorities, and her first selection

PHOEBE INGLEBY relishes the unexpected power of pins, zips and buttons to stitch together stories of connection, resistance and ancestral memory

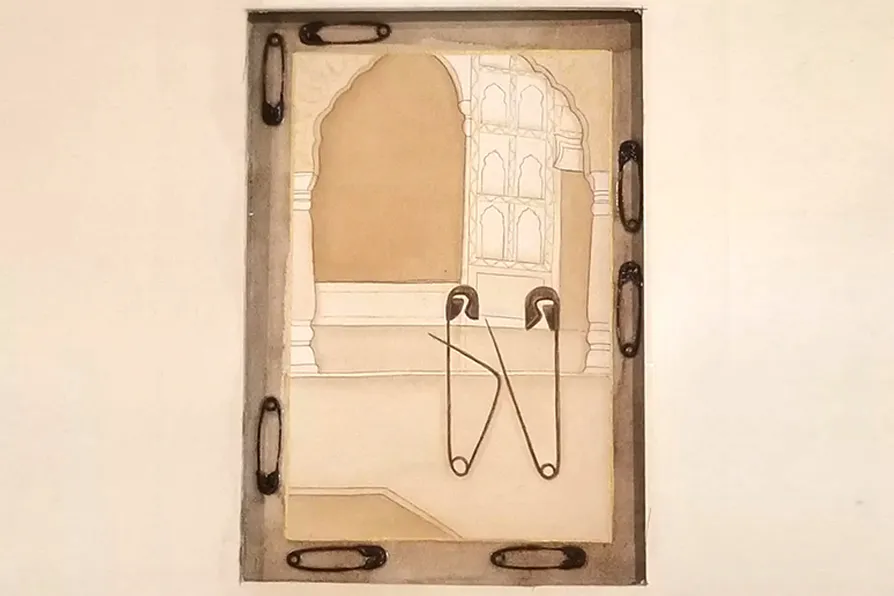

Iman Asif, گفتگو (Conversation), 2024, Watercolour, safety pins and tea stain on wasli. [Pics: Lottie McCrindell]

Iman Asif, گفتگو (Conversation), 2024, Watercolour, safety pins and tea stain on wasli. [Pics: Lottie McCrindell]

House of Haberdash

Torriano Meeting House, Kentish Town, London

★★★★★

TUCKED away on a street in Kentish Town, the Torriano Meeting House looks like a relic from another age. With its wooden facade and broad-paned windows, it could be mistaken for an old shopfront – one of those rare spaces spared the churn of redevelopment. But something restless stirs inside.

House of Haberdash, curated by Lottie McCrindell, is a group exhibition bringing together over 30 artists, poets and designers. Their work draws from the language of the haberdashery: fabric is bundled, stitched and draped in a choreography of texture; hats swing in mobile constellations; scraps, ribbons and shells bloom into installations. Materials once relegated to sewing boxes are celebrated anew – a haberdashery unspooled and reimagined.

McCrindell describes the word “haberdashery” as “elastic,” an apt metaphor for the exhibition. Typically referring to the overlooked minutiae of dressmaking – buttons, ribbons, pins – these items become portals, fastening histories to bodies and stitching memory into public form. The artists explore the body, borders, memory and repair through textiles, sculpture, painting, poetry and fashion.

In an era of fast fashion and image saturation, the exhibition proposes an alternative rhythm – slower, attentive, and grounded in care. It contests disposability and distraction, offering instead a reparative way of seeing.

A standout is Kate Neil’s Kite For Palestine (after Refaat Alareer) (2024). Created in collective grief and solidarity with Palestine by her local maker community, the kite was inspired by Refaat Alareer’s poem If I Must Die, Let It Be A Tale (2011). Alareer, a Palestinian poet and professor, was killed in an Israeli air strike on Gaza City in 2023. Neil’s kite is intricately embroidered with Palestinian symbols – olive branches for peace, cypress trees for endurance. The kite was flown on Parliament Hill during Eid Kite Day, carrying Alareer’s words into the sky.

This dialogue between text and textile recurs throughout. McCrindell’s curatorial platform TEXTUS explores their intersection, harnessing the power of poetry, metaphor, and interdisciplinary collaboration. It brings together creatives from across disciplines to explore, critique, and reimagine fashion and textile environments, design, history, culture, language, and logic. Language and textile – bound by shared etymology and idioms like “weaving a story” or “tying up loose ends” – have long transmitted ideas and preserved collective memory.

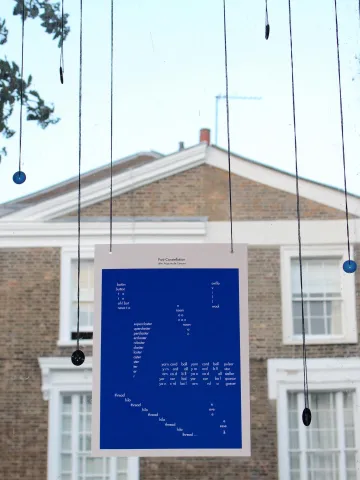

Leo Boix’s sculptural poem Post-Constellation (After Augusto de Campos) (2025) hangs suspended by thread encircled by a constellation of buttons. Drawing on Brazilian concrete poetry, Boix treats language as a spatial medium, where the visual arrangement of words matters as much as their semantic meaning. Stanzas slip into Spanish, forming clusters that echo patterns of migration.

Simiran Lalvani’s Toggles (2025) plays on the word’s dual meaning – coat fasteners and the digital switch – to consider how the postdigital turn has reshaped the status of objects and images. Lalvani asks how we connect, disconnect and toggle between selves in a postinternet condition where the boundary between virtual and material has grown unstable.

The body surfaces in Scarlett Pochet’s Operation Sempstress (2025), a carved wooden relief reimagining haberdashery pockets as internal organs. Scissors and pins are inset like surgical tools, recalling the board game Operation. Pochet explores garments as extensions of the self – inseparable from the bodies they dress.

Nirrhit Pal’s Zipper Series III: Zipper People (2025) is a silicone torso scaled from his own body with a zip embedded in the stomach. Rooted in his short story of a monster-haunted borderland where communities brutalised by paramilitary forces mutate to survive, the work is an allegory for life in north-east India under military occupation. The zip becomes a metaphor for wounds inflicted by militarised borders, how trauma is etched onto the body, and how communities adapt to survive.

There’s tenderness and wit too. In The Weight Of Small Things (2023) Sarah Taylor sculpts with old tights stuffed with her children’s socks. The nylon cradles the socks like a body might a child – gently, imperfectly, with love and exhaustion in equal measure. Taylor captures the invisible labour and weight of motherhood: the pull, the strain, the holding-together of everything.

The venue reflects the exhibition’s ethos. Torriano Meeting House – known for poetry readings, workshops and grassroots activism – has served as both cultural hub and political commons for decades.

Why does haberdashery resonate now? Perhaps because it gestures to a slower, more attentive world, where care is lavished on small acts: a button resewn, a hem repaired. These humble objects remain with us, yet risk being forgotten. House of Haberdash restores them through acts of fastening, mending and remembering.

In a world coming apart at the seams – ecologically, politically, spiritually – this exhibition insists nothing is too small to matter. A scrap of fabric can hold a life, a lineage, a memory. Craft here is not nostalgic, but critical labour: staying with what frays, piecing together what is broken, refusing to let go.

House of Haberdash runs until August 10 2025. For more information see: torriano.org