ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes two exhibitions that blur the boundaries between art and community engagement

Artist in residence of the human conscience

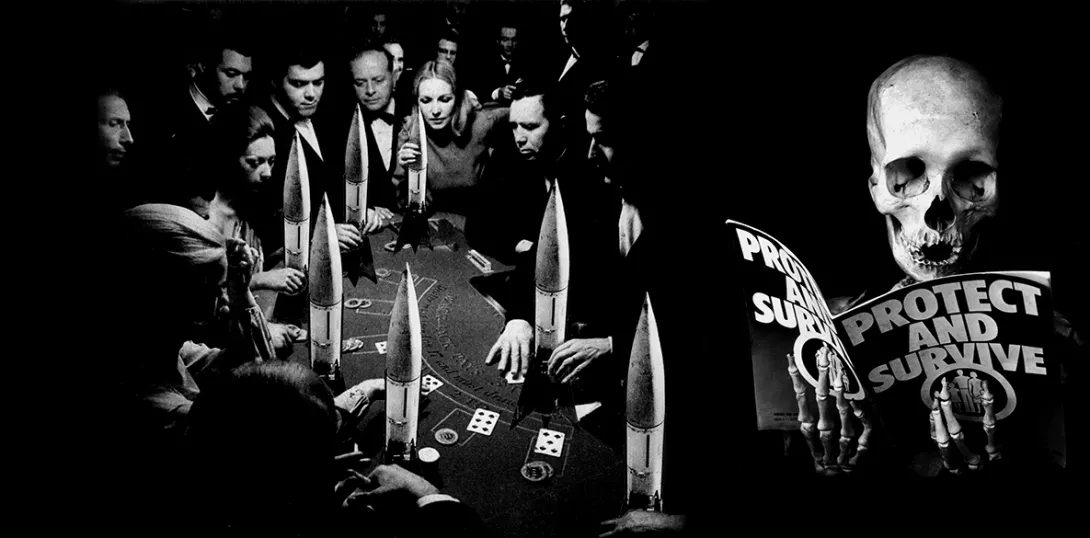

JAN WOOLF applauds art that has not only documented the anti-war and anti-capitalist movement but been an integral part of it

Peter Kennard: Archive of Dissent

Whitechapel Gallery, London

SINCE the early 1970s, Peter Kennard’s art has not only documented the anti-war/ anti-capitalist movement but been an integral part of it; both as revelation and stimulus.

Indeed, he reveals their links and stimulates the processes of resistance. He may be the only artist whose art — and it is art, not propaganda — has appeared on the streets and aloft at demonstrations as well as in newspapers and galleries. You could consider him the artist in residence of the human conscience.

“My art,” he says, “erupts from outrage at the fact that the search for financial profit rules every nook and cranny of our society. Profit masks poverty, racism, war, climate catastrophe and on and on …”

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

MARJORIE MAYO recommends an exhibition that asserts Palestinian history, culture and creativity in the face of strategies to erase them

Co-curator TOM WHITE introduces a father-and-son exhibition of photography documenting the experience and political engagement of Chilean exiles

CHRISTINE LINDEY guides us through the vivid expressionism of a significant but apolitical group of pre WWI artists in Germany

HENRY BELL steps warily through the collection of a Glaswegian war profiteer to experience his collection of Degas’ remarkable images of working people