JULIA THOMAS unpicks the mental processes that explain why book-to-film adaptations so often disappoint

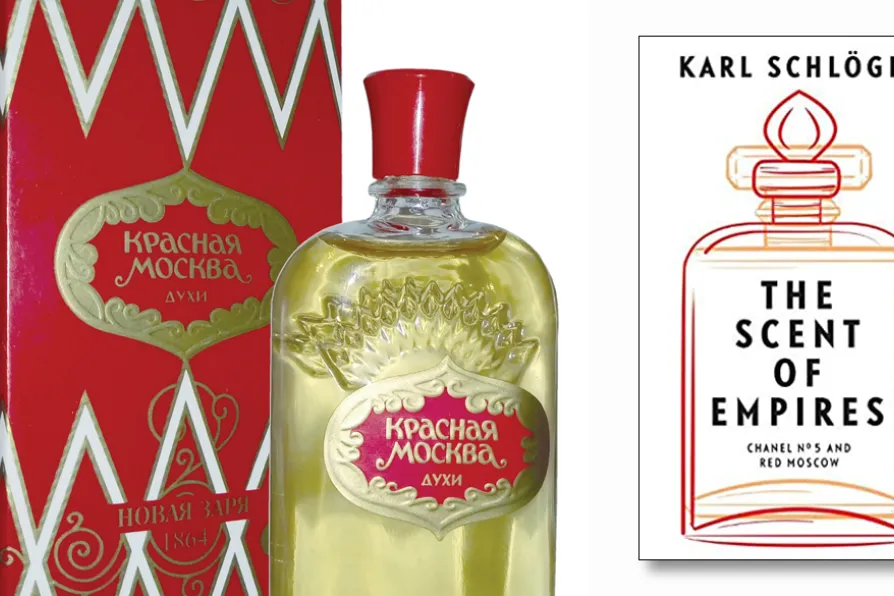

KARL SCHLOGEL’S book is an intriguing history of the development of two perfumes in two different worlds, one of which is globally famous, the other almost unknown outside its homeland.

He begins his account in imperial Russia, where a highly developed perfume industry thrived in Moscow. They were led by two French perfume houses, Brocard & Co and Rallet & Co, with their head perfumers — August Michel at Brocard and Ernest Beaux at Rallet — working on closely related perfumes in honour of the tricentenary of the Romanov dynasty.

The October Revolution brought to an end this world of glittering excess for the few. But scents can survive revolutions and Beaux fled back to France, presenting his formula to Coco Chanel.

TONY FOX invites readers to come and hear the story of the remarkable Liverpudlian International Brigader Alexander Foote