SOLOMON HUGHES reveals how six MPs enjoyed £400-£600 hospitality at Ditchley Park for Google’s ‘AI parliamentary scheme’ — supposedly to develop ‘effective scrutiny’ of artificial intelligence, but actually funded by the increasingly unsavoury tech giant itself

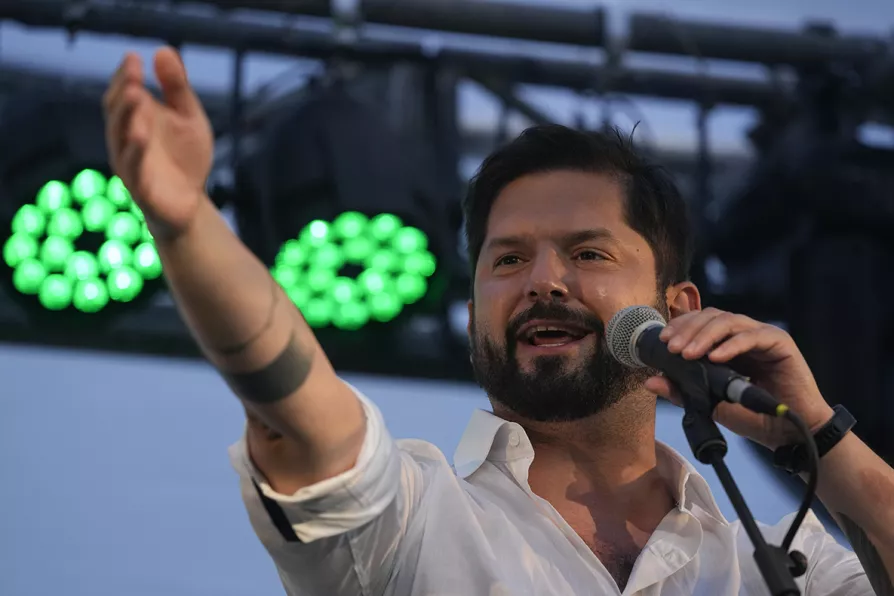

Chilean presidential candidate Gabriel Boric speaks to supporters during a closing campaign rally in Casablanca, Chile, Thursday, November 18, 2021

Chilean presidential candidate Gabriel Boric speaks to supporters during a closing campaign rally in Casablanca, Chile, Thursday, November 18, 2021

THE most controversial and surprising aspect of the presidential and parliamentary elections of November 21 in Chile was the consistent political and electoral advance of the ultra-right and the traditional established right. They won the first round of the presidential elections and came close to obtaining 50 per cent in the Senate and the lower house.

In contrast, the progressive and left-wing sectors did not perform badly. The presidential candidate of the forces of transformation, Gabriel Boric, came within two points of the far-right Jose Antonio Kast (25 to 27 per cent respectively of the vote), with a good chance of overtaking him in the second round.

In parliament, the combined votes of the social democratic, Christian democratic, progressive and left-wing parties are close to 50 per cent.

This is a reflection of what is described as “polarisation in Chile,” in that there are two major forces in the dispute over the political project for the country, although it could be added that it also reflects the socio-economic polarisation in Chilean society, which is often made invisible.

Kast certainly represents the continuity of the neoliberal model, of an authoritarian institutional scheme, a regression in achieved rights, he is against a new constitution, he is a vindicator of the civil-military dictatorship, he is anti-immigrant and emphasises the discourse “of law and order” with strong repressive features.

Boric is in favour of dismantling neoliberalism and establishing a rights-based state, seeks a participatory democratic institutionality, promotes more and better social rights, supports the establishment of a new constitution, seeks to meet the citizens’ demands expressed in the revolt of 2019, proposes changes in the police and unrestricted respect for human rights.

The point is that many factors intersect in electoral processes. Not everything is defined by programmatic proposals. Thus, in Chile, the 54 per cent abstention rate had an impact. Also the ultra-conservative discourse on order and security, in the face of the increase in drug trafficking, delinquency and violent situations in popular mobilisations.

The narrative of “social fear” is influential, suggesting that changes and transformations bring instability and disorder.

On the other hand, broad sectors of the electorate expressed support for proposals for social progress, citizens’ demands, profound changes in society, an end to privatisation schemes, repudiation of repression and authoritarianism, the search for better living conditions, support for citizen protest and no fear of profound changes in Chilean society.

In any case, a better reading of the political reality is needed, because it was evident that the result of the presidential and parliamentary elections broke the trend that had been defining Chile since the social revolt of 2019.

The triumph of the plebiscite for a new constitution with almost 80 per cent approval, and the victories of the progressive and leftist sectors in the municipal, gubernatorial and constitutional convention elections are indicative of progressing change.

While the forces of transformation maintained their level of electoral support, the far right and the right extended theirs.

The battle ahead, some three weeks before the second round of the presidential elections, will be raw, intense and defining.

Boric and the forces that support him have the obvious challenge of overcoming the two points that separate him from Kast and in this he must have the capacity to call on the electorate identified with social democracy, Christian Democrats, progressives, certain liberal sectors, but also sectors of the left that did not vote for him in the first round.

In addition, he will appeal to sectors of the rural areas, the urban poor, workers, middle-class people, the worlds of culture and feminism, and leave aside a certain discourse and aesthetic that only targeted young people and urban areas with a concentration of middle-class people, as shown by the fact that he did well electorally in the Metropolitan Region and in Valparaiso, and poorly in the northern and southern regions of the country.

Kast will bet on growing towards the electoral base of the traditional organic right (which ran Sebastian Sichel as candidate, coming fourth), the middle class, sectors of popular neighbourhoods, in rural areas, segments of the richest percentage of the population.

Both have the challenge of convincing those Chileans who did not vote in the first round.

What is to come will also be influenced by the performance of each sector in the campaign. The unforced errors, the role in the television and radio debates, the management of the spokespersons, the clarity and concreteness of the proposals, the use of social networks, the work with traditional propaganda, the work in the streets and neighbourhoods, the work of the armies of brigadistas and promoters and the way in which they deal with the political/social contingency, which in Chile is quite convulsed at present.

The fact remains that neither Boric nor Kast, nor the forces that support them, can claim victory at the moment. That makes everything more challenging and a battle of significant proportions is to be anticipated in the weeks to come. And, of course, Chile will be voting for two totally different political projects for its future.

Hugo Guzman ist editor of El Siglo/The Century the paper of the Communist Party of Chile.