CHRISTOPHE DOMEC speaks to CHRIS SMALLS, who helped set up the Amazon Labor Union, on how weak leadership debilitates union activism and dilutes their purpose

KEITH BARLOW examines the 1975 referendum that saw Britain vote to stay in the EEC, revealing how Tony Benn understood that EU free-market principles and capital movement rules would tie the hands of any government putting people’s interests before corporate profits

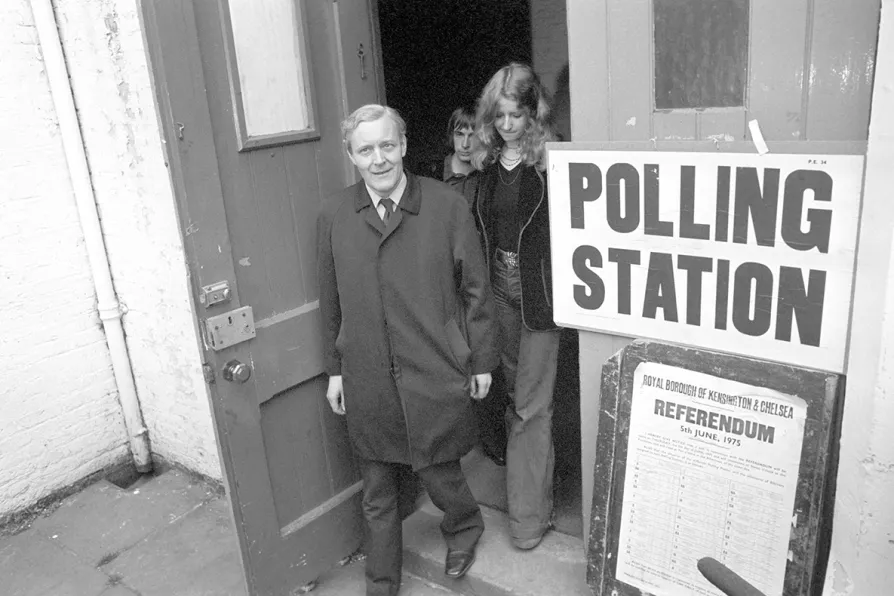

Then Industry Secretary Tony Benn and his daughter Melissa, 18, leave a church hall polling station on Portobello Road, after casting their votes in the European Referendum on the Common Market, June 1975

Then Industry Secretary Tony Benn and his daughter Melissa, 18, leave a church hall polling station on Portobello Road, after casting their votes in the European Referendum on the Common Market, June 1975

THE FIRST British referendum on the EU, or European Economic Community (EEC) as it was then called, took place 50 years ago today. It was not on joining the EEC as Britain was already a member, but whether to stay in or leave. Britain’s Tory government had already taken Britain into the EEC in 1973 with no referendum. Referenda had taken place in the early 1970s in three other European countries seeking membership (Ireland and Denmark voted “yes” and Norway “no”). But there had been none in Britain.

Then-prime minister Edward Heath had had every reason to fear a referendum. There were wide concerns over the consequences membership would have for matters such as food prices and jobs, not overlooking the unpopularity of the Conservative government.

When Labour got back into office in March 1974, with Harold Wilson once again becoming prime minister, a pledge was made to renegotiate the terms of EEC membership and that this would be followed by a referendum. The referendum took place on June 5 1975.

The question of British membership had already been raised much earlier in the 1960s but had ultimately been blocked by France’s then-leader, De Gaulle. At that time, Britain’s Communist Party, the bulk of the trade union movement and most others on the left said “no.”

The free-market principles anchored in the Treaty of Rome, and especially the freedom of movement of capital and goods, were seen to pose a threat to jobs as well as to the future of Britain as a major industrial nation. EU regulations would tie the hands of any government seeking to enact economic and social policies that put the interests of the people before the corporate interests of big business.

These fears were not unfounded. A decade later, they were outlined in the Labour government’s August 1974 white paper The Regeneration of British Industry, published when Benn was secretary of state for industry.

There it was stated that, “since the war, we have not as a nation been able … fully to harness the resources of skill and ability we should be able to command. We have been falling steadily further behind our competitors. We have not found the self-confidence to bridge that gap. … In 1971, investment for each worker in Britain’s manufacturing industry was less than half of that in France, Japan or the US, and well below that of Germany or Italy. In spite of the measures … taken since then, it has still lagged behind; indeed, it was significantly less in 1972 and in 1973 than it was in 1970 … In the last 10 years, the rate of direct investment by British firms overseas has more than trebled.”

Because in 1974 the new Labour government was divided on the question of EEC membership, the white paper avoided positioning itself. However, a close reading would indicate that Benn was well aware of the implications of staying in the EEC for Britain’s future as a major manufacturing nation.

The 1974 white paper made proposals for extending public ownership and state involvement in strategic industrial sectors. Modest though they were, they formed the basis of the Labour government’s Industry Bill. In the subsequent EU referendum campaign, Benn’s proposals were attacked by those opposed to extending public ownership as contravening the Treaty of Rome.

Benn himself was a firm supporter of the Alternative Economic Strategy (AES). This was widely backed in the labour movement, and its key provisions were anchored in both of the two Labour election manifestos of 1974. Benn was clear that withdrawal from the EEC was necessary if the AES was to be put into effect. Among Labour MPs, support was less enthusiastic. In the Cabinet, a majority was for staying in the EEC. It was equally opposed to key elements of the AES.

At a major rally in Wakefield on May 28 1975, in support of the campaign for leaving the EEC, I was able to ask Benn what the implications of voting to stay in the EEC would have on his Industry Bill. He answered that for the first time in British history, an institution outside the country would be able to take a minister to court in Britain for implementing proposals which had been passed by Parliament.

I never forgot Benn’s answer, which raised the question of how left policies can be implemented by any government coming to office in a member state of the EU. In later years, this question was to feature more and more as ratification of key EU treaties such as Maastricht, Amsterdam and Lisbon was forced through Parliament. It was, of course, an issue in the referendum campaign in 2016 when Britain “corrected,” as it were, the 1975 result.

Eight days after the Wakefield rally, the referendum took place. There was a two-to-one vote in favour of staying in. On the following day, Benn was sidelined in a Cabinet reshuffle. Subsequently, key provisions in his Industry Bill were watered down.

Fifty years on from this referendum, it is important to remember Benn’s position on the EEC and its implications for the left. His words remain as relevant as ever. Running to the EU for cover has never been an option.

Dr Keith Barlow is the author of the Labour Movement in Britain from Thatcher to Blair (Peter Lang, 1997).