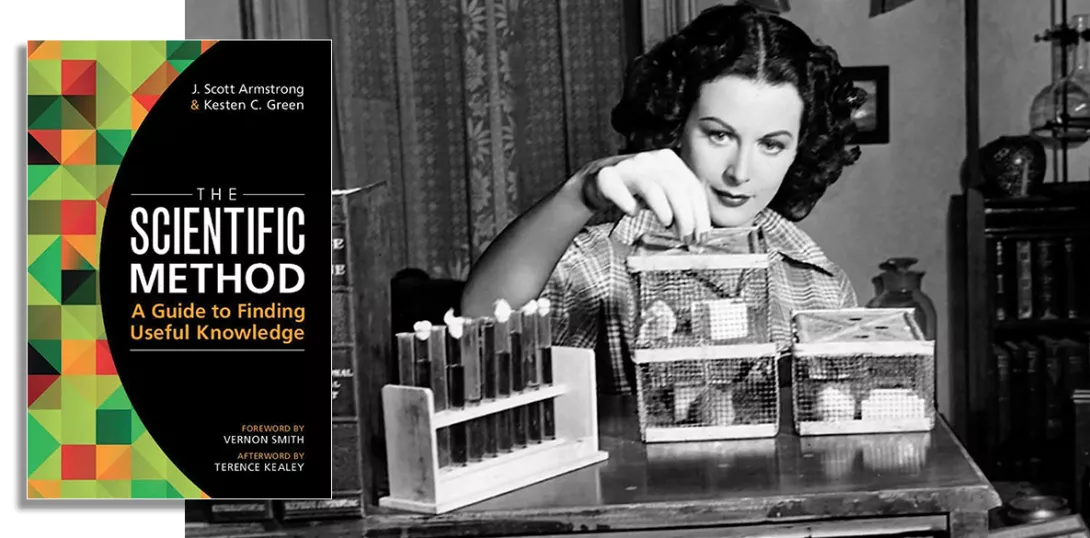

The Scientific Method

by J Scott Armstrong and Kesten C Green

Cambridge University Press, £22.99

MANY years ago, as a researcher in computer-based learning, I witnessed the corrosive impact of corporate interference in academic research. Projects were distorted by interpersonal rivalry, institutional bullying and obsessive career management.

These pressures continue to affect the acquisition of knowledge and are worthy of the kind of serious investigation promised – but not delivered – by The Scientific Method. The book is pitched as an antidote to the cognitive biases and socio-economic influences that undermine the value and validity of science; unfortunately, it is riddled with precisely the kind of careless thinking it rails against.

Armstrong and Green proclaim the importance of objectivity in science, while peppering their guidelines for scientists, educators and journalists with subjective concepts and clunky anecdotes.

For example, they set out a “Compliance with Science Checklist.” This includes tangible items already familiar to trained and well-read practitioners (clear reporting, objective design, comprehensive disclosure, reliable data); but also poses fuzzier questions about the importance of research. The notion of “importance” is strikingly subjective. Important to whom? Which segment of society will benefit?

The answer becomes all too clear when the authors quote from right-wing luminaries such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, and call for the privatisation and deregulation of research. It is suggested scientists are deflected from “useful” investigations by the state’s perverse incentives, such as grant funding. The mantra that scientists in private corporations and think tanks work more efficiently, and to greater public benefit, than government-sponsored academics plays on repeat throughout the book.

There is substantial evidence to the contrary. In Science and the Corporate Agenda, 2009, Chris Langley and Stuart Parkinson noted that the commercialisation of science triggers bias, conflicts of interest, a narrowing of the research agenda, and misrepresentation of results.

More recently, Professor Erik Millstone, an authority on food safety, noted serious flaws in research on the safety of the artificial sweetener Aspartame. He told the BBC’s Panorama programme “About 90 per cent of the reassuring studies were funded by the large chemical corporations that manufacture and sell aspartame … I saw that as an expression of a profound and very dangerous bias.”

The book champions quantitative methods and expresses deep-seated scepticism about the use of non-experimental evidence. In spite of this, it relies heavily on personal anecdotes, biographical snippets and poorly supported assertions.

For example, work on radio guidance systems for torpedoes by Hollywood actor Hedy Lamarr (spelt incorrectly in the text and index) is cited as evidence that self-funded research can be effective and beneficial. The authors offer no detail about Lamarr or her work, relegating the story to the status of non sequitur. There are similarly feeble allusions to Sinclair Lewis’s novel Arrowsmith, and biographies of the scientists Milgram and Faraday.

It gets worse. At one stage, Armstrong and Green, champions of objectivity and experimental evidence, assert with no trace of irony that “the subconscious helps in solving problems.”

Narrow, unconvincing and mired in free market conservatism, The Scientific Method is a deeply dispiriting book, leavened only by moments of unintentional humour.