ELEANOR DOBSON reflects on a stark visual record of the violent desecration of Tutankhamun’s mummified remains

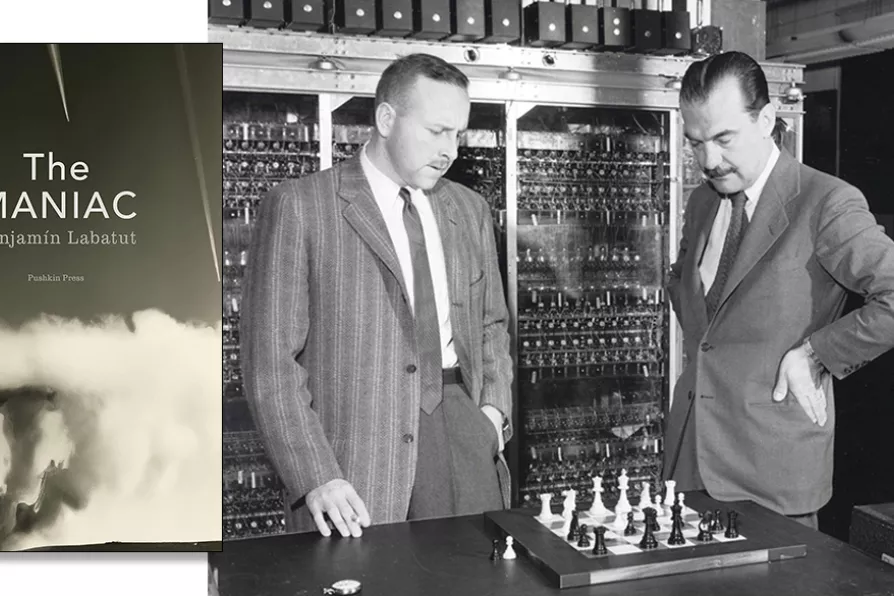

Paul Stein and Nicholas Metropolis, both veterans of Oppenheimer's Manhattan project, play “Los Alamos” chess against the MANIAC. The MANIAC became the first computer to beat a human opponent at chess in 1956.

[Los Alamos National Laboratory/CC]

Paul Stein and Nicholas Metropolis, both veterans of Oppenheimer's Manhattan project, play “Los Alamos” chess against the MANIAC. The MANIAC became the first computer to beat a human opponent at chess in 1956.

[Los Alamos National Laboratory/CC]

The Maniac

Benjamin Labatut, Pushkin Press, £20

FORTY years ago, long before anyone used the phrase “deep learning algorithm” on News at Ten, I was writing neural network simulations of social and biological systems. My co-workers and I had misgivings about the reductive nature of our programmes – factors that couldn’t be coded tended to be ignored – but we were intoxicated by the pleasure of problem solving and the pioneering nature of our work.

The seductive nature of scientific discovery, an endeavour driven by the under-examined notion of progress, is at the heart of The Maniac. Benjamin Labatut’s ambitious novel explores two centuries in the history of ideas to untangle an urgent and fascinating mystery. Anyone taking a critical interest in AI knows the tools we have developed and the scientific methodologies that yielded them are leading humanity to the brink of a moral and existential crisis: but how did we get to this point?

To answer this question, Labatut examines the intellectual and private lives of people who played a pivotal role in the creation of our digital world – physicists, logicians, mathematicians, computer scientists and masters of Go, the ancient game of strategy.

The structure of the book is complex, but ingeniously suited to the themes it sets out to address. The Maniac is a symphony in three movements: it begins with a third-person account of the tragic story of Austrian physicist Paul Ehrenfest, driven to insanity and an act of murder/suicide by the rise of Nazism and the chaotic uncertainties of quantum physics. It ends with a gauntlet flung down to Masters of Go, the complex strategy boardgame, by the creators of learning machines. The gambit-by-gambit reports of the Go battles between Lee Sedol and Deepmind Technologies’ AlphaGo programme are lucid and compelling.

The central, and longest, movement concerns the astonishing life of John von Neumann, the polymath who originated game theory, contributed to the design of the first cellular automata, introduced the first programmable computers and acted as consultant to the Manhattan Project. In fact, it was the hawkish von Neumann who chose Hiroshima and Nagasaki as targets and helped maximise the “kill rate” of US atomic bombs.

The story of von Neumann and the ideas he championed unfolds through a series of witness statements from his associates, family, enemies and the colonel who attended his deathbed. Voices are cleverly differentiated: some reminiscences are punchy and expressive, others are delivered in rambling sentences with multiple clauses; some prose is flat and journalistic, some poetic and packed with emotion.

These testimonies highlight the brilliant intellects of von Neumann and his network – as well as their obsessions, betrayals, suspicions and haughty sense of superiority over the rest of humanity. Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist Richard Feynman recalls the tribulations of working at the secret army installation at Los Alamos, before contemplating the link between von Neumann’s MANIAC (mathematical analyser, numerical integrator and computer) and the nuclear arms race. Klara Dan, coding expert, former skater, von Neumann’s wife, discloses details of a fiery marriage and reflects on the talent and ambitions of a group of damaged men. The Norwegian-Italian mathematician Nils Aall Barricelli reflects on his quest to create digital life and his schism with the “scoundrel” von Neumann.

Labatut resists the urge to lecture his readers, but his tales of privileged but deeply flawed people gradually illuminate the way in which abstract ideas interacted with personal experience, group processes and the political zeitgeist to lay the foundations for some of the most dangerous technologies of the 21st century.

The Maniac is an erudite, entertaining and important book. It challenges the assumption that the science exemplified by von Neumann is pure, objective and politically neutral. Furthermore, it highlights the need for a shift of focus from what our tools can achieve to what they ought to achieve. All too often in capitalist societies, the fact that something becomes possible implies it is inevitable.

JOHN GREEN’s palate is tickled by useful information leavened by amusing and unusual anecdotes, incidental gossip and scare stories

ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes an exuberant blend of emotion and analysis that captures the politics and contrarian nature of the French composer

ANDY HEDGECOCK admires a critique of the penetration of our lives by digital media, but is disappointed that the underlying cause is avoided