GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends an important, if dispiriting book about the neo-colonial culture of Uganda under Yoweri Museveni

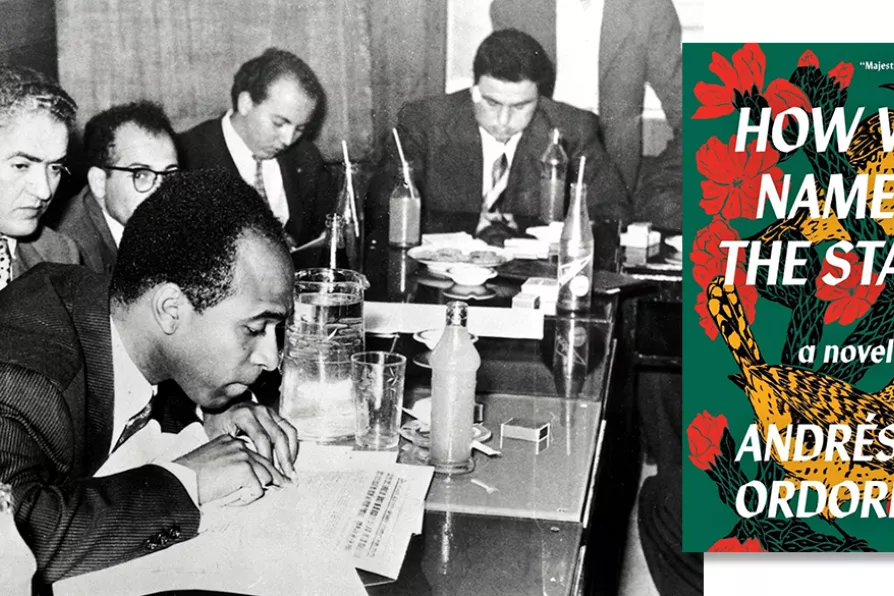

Frantz Fanon at a press conference during a writers' conference in Tunis, 1959

[Public Domain]

Frantz Fanon at a press conference during a writers' conference in Tunis, 1959

[Public Domain]

EVEN if Andres Ordorica’s Young Adult coming-out novel How We Named The Stars (Saraband, £10.99) didn’t mention Frantz Fanon, his shadow would fall across it.

It is a subjective account — like that template for YA fiction, Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye — that describes a 19-year-old Mexican American’s tragic crush on a white room-mate in his first year at university. His parents are first generation Mexican immigrants, but his culture and language is entirely that of the contemporary US.

He is “brown,” but his crush is an amalgam of gay white stereotypes: “washboard” abs, square chin, blond hair, blue eyes, a “gazelle” in Nike sweatpants and Timberland trainers — less a person, in other words, than a poster and a clothes rack. This “white” object of desire is both idealised and commodified, a blank cipher into which, it is presumed, the adolescent gay reader, white or otherwise, can project their own desires and fantasies.

On the centenary of the birth of the anti-colonial thinker and activist Frantz Fanon, JENNY FARRELL assesses his enduring influence

LEO BOIX introduces a bold novel by Mapuche writer Daniela Catrileo, a raw memoir from Cuban-Russian author Anna Lidia Vega Serova, and powerful poetry by Mexican Juana Adcock

FIONA O’CONNOR is fascinated by a novel written from the perspective of a neurodivergent psychology student who falls in love