Rosarita

Anita Desai, Picador, £12.99

ON the surface, Rosarita is modest in both form and theme. A 94-page novella dealing with an unsettling encounter and its psychological aftermath, its apparent simplicity is deceptive. Like Dr Who’s Tardis, Anita Desai’s story is mysteriously bigger on the inside.

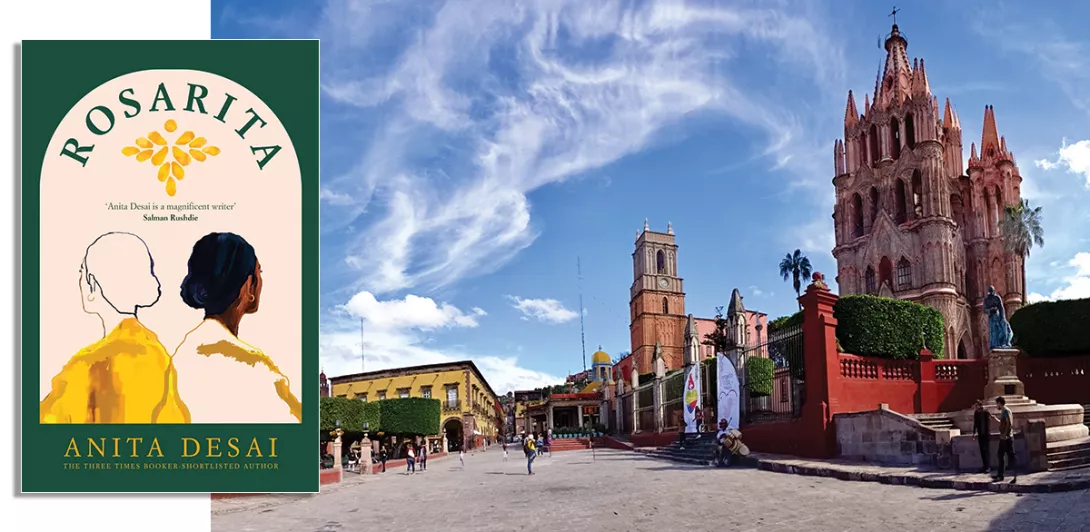

On the opening page, Bonita, a young Indian woman studying Spanish in Mexico, is sitting in a municipal park in the city of San Miguel de Allende, “facing the pink spikes and spires of the Parroquia [parish church]”. Suddenly, she spots an elderly woman “rising in a flurry of skirts and scarves,” and a curious conversation ensues.

The woman, Vicky, initially referred to as The Stranger, claims Bonita is “the image” of her adored friend, Rosarita, who studied art in San Miguel many years before. To the best of Bonita’s knowledge, her late mother, Sarita, was not inclined to paint or travel abroad, but The Stranger’s passionate recollections soften her incredulity.

After dredging the silt of childhood memory, and reflecting on the mysteries uncovered, Bonita imagines a bridge between the mother she knew and the traveller and artist beloved by Vicky. She speculates that her mother attended an exhibition highlighting similarities between the violence of the Mexican Revolution and that of the Partition of India. This, in turn, may have inspired her trip to Mexico and the desire to express herself through painting.

Having decided Rosarita may have been Sarita’s adopted identity, Bonita takes Vicky on a chaotic and emotionally charged tour of locations where her mother is alleged to have lived, studied and painted. The supporting characters encountered on the journey, like those recalled in flashback, are deftly sketched and convincing.

Desai is preoccupied with life’s messy discontinuities, so this is not a book for those who insist on closure and resolution. For example, we never discover whether Vicky is a well-meaning eccentric or a self-serving grifter, but it doesn’t really matter. She’s a lively figure who provokes Bonita to reflect on the restrictions imposed on her mother by her husband, in-laws and post-colonial domestic life.

Some readers may be irritated by Bonita’s passivity – she is a woman swept along by circumstance rather than one making rational decisions – but she isn’t the story’s protagonist in the conventional sense. Her actions and streams of consciousness are delivered in the second person present tense. The effect of this is to diminish the reader’s identification with her and to heighten our sense of direct involvement in an unresolved mystery.

Desai casts you – the reader – in the role of epistemological detective: you investigate the provisional nature of identity; you decide whether it is ever possible to completely know another person; and you navigate the borderland of imagination and memory.

The book’s brevity belies its complexity. The precision and poetry of Desai’s language – her detailed observations of costume, gesture, architecture and landscape – weaves an intricate tapestry of symbols. This, in turn, supports the book’s philosophical enquiries and reflections on family, exile, history, violence, female agency and the social relevance of creativity.

A slender but costly book — £12.99 seems steep for a novella — Rosarita is a beautifully written and demanding exploration of human beings and the attachments we form.