GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

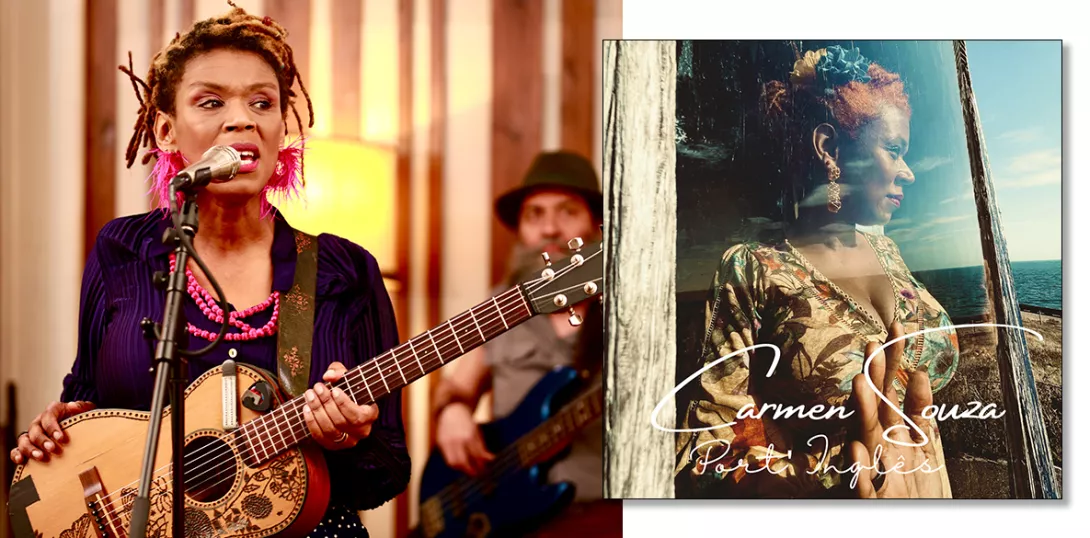

‘Jazz was created for and by the African-American community and was always political by its very nature’

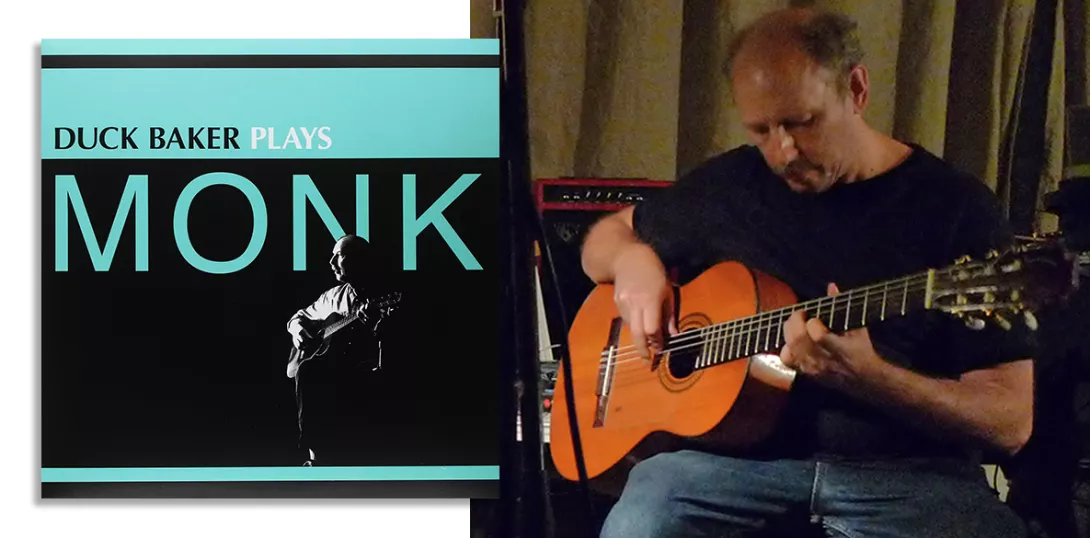

CHRIS SEARLE speaks to celebrated US guitarist DUCK BAKER

“THELONIOUS Monk is not only our greatest genius, no-one else is even close.”

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

Chris Searle speaks to singer CARMEN SOUZA

STEVE JOHNSON, CHRIS SEARLE and KEVIN BRYAN review new releases from Brooks Williams and Aaron Catlow, Kris Davis Trio, PP Arnold, Rum Ragged, David Virelles, Mark Harrison Band, Linda Moylan, Catriona Bourne, Julie Driscoll, Brian Auger & The Trinity

CHRIS SEARLE speaks to Glaswegian guitarist JIM MULLEN

KEVIN BRYAN, CHRIS SEARLE and TONY BURKE review new releases from Dickey Betts, Little Johnny England, Greenslade, Benet McLean, Sam Newbould, Sofia Jernberg/Alexander Hawkins, compilation: Walking To New Orleans, compilation: This Is Goldwax: 1964-1968, Jack Bruce