MARIA DUARTE picks the best and worst of a crowded year of films

Yesterday’s future

Orwell’s 1984 was both timely and prophetic; this feminist reworking is well-written but inconsequential, writes CHRIS MOSS

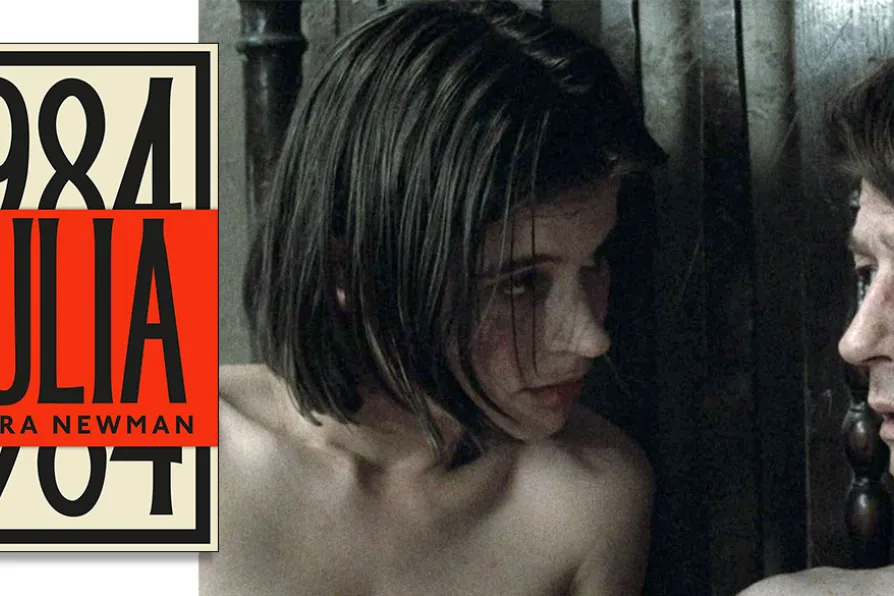

WHAT ROT: Suzanna Hamilton and John Hurt in Michael Radford’s 1984

[IMDb]

WHAT ROT: Suzanna Hamilton and John Hurt in Michael Radford’s 1984

[IMDb]

Julia

Sandra Newman, Granta, £18.99

MANY people read George Orwell’s 1984 at school before they’ve come across other literary dystopias. Given the unrelenting, very English gloom that pervades it, chances are it puts them off the genre for good.

Savvy teachers talk up the author’s inventiveness in coining terms like Newspeak, Big Brother, the Ministry of Truth, Ingsoc etc. These have novelty value when first encountered and provoke debate, but have become cliches through overexposure. Orwell’s prescience as regards surveillance is obvious, but its restating has become tiresome and simplistic.

Similar stories

SARAH TROTT explores short fictional slices of life in the American midwest from a middle-aged and mostly female perspective

JESSICA WIDNER explores how the twin themes of violence and love run through the novels of South Korean Nobel prize-winner Han Kang

While German leaders talk independence and even the Tories promise to speak truth to America, the Labour leader grovelled before a president whose comments he once called ‘absolutely repugnant,’ writes PETER KENWORTHY

PAUL DONOVAN applauds an adaptation that draws out the contemporary relevance of George Orwell’s satire