GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends an important, if dispiriting book about the neo-colonial culture of Uganda under Yoweri Museveni

RON JACOBS welcomes a timely biography of a contemporary of Marx and Engels who advocated revolutionary socialism

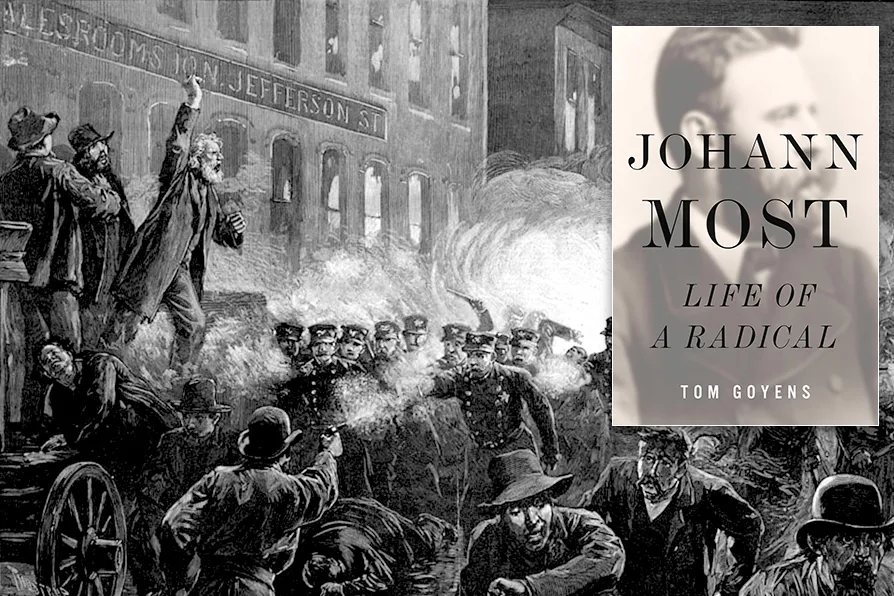

Wood engraving depicting the Haymarket riot [Pic: Thure de Thulstrup/Public Domain]

Wood engraving depicting the Haymarket riot [Pic: Thure de Thulstrup/Public Domain]

Johann Most: Life of a Radical

Tom Goyens, University of Illinois Press, £22.99

JOHANN MOST was born February 5 1846 in Augsburg, which was then located in the state of Bayern (Bavaria), soon to be part of the new nation of Germany. He was one of the best-known leftist writers and activists when he began adopting the politics of anarchism.

Over the course of his political life, his political identity would alternate between the two theoretical cousins of socialism and anarchism, constantly searching for a synthesis that not only intensified his understanding of the world, but also could be applied in the particular moment.

Although he was one of the better-known revolutionaries and labor organisers of his time in the United States and Europe, this new biography of Most by Tom Goyens is one of only three or four written for the English-speaking audience.

Goyens’s text begins with a tale of Most’s May 1886 New York City arrest following the deaths of police and protesters in Chicago’s Haymarket Square during a mass protest for the eight-hour day and other worker’s rights. The protest is known in most mainstream histories as the Haymarket Riot, mostly because someone set off a bomb killing seven policemen. This was after the police had attacked a rally the previous day and killed two protesters. After the bomb had been tossed into the rally, police fired back.

All told, 11 people died that day; four civilians and seven police officers. Most was arrested in New York for a speech he had given after the Haymarket deaths — a speech in which he brandished a rifle and called for revolution.

From that beginning, Goyens’s biography returns to Most’s childhood in Germany, his education, his fascination with the theater, his employment as a bookbinder and his travels. The reader is told about Most’s facial disfigurement, the result of an infection that was unattended to for years because of his family’s poverty.

The story revealed in this section is one of a restless, intelligent and politically curious bohemian with a knack for words. His speechmaking against the monarchy and Bismarck’s militaristic vision of Germany got him in trouble more than once.

Most ended up in Vienna, Austria from 1868 to May 1871. Although he had lived there before, it was during this time that Most’s politics became socialist.

After joining the Bookbinders, Leather Workers and Case Workers Union, Most’s public profile grew as his speeches drew attention among his fellow workers. Unfortunately for his working life, his speeches were also drawing attention from the media, which did not approve of his ideas.

It was during this time that his writing and speechmaking found a tone that was both incendiary and educational. The combination drew applause from his fellow workers and organisers and unwanted attention from the Establishment.

In addition to his speeches and newspaper writing, Most and fellow socialist Andreas Scheu wrote, produced and performed in four plays that were political in nature and seen by thousands. Drama critics praised the drama titled Die Reise nach Amerika, oder: Das Wiedersehen (The journey to America: or the Return), while also acknowledging Most’s acting talent.

Goyens writes that Most’s role in shaping Austrian socialist culture through his theatrical pieces was still being written about in the middle of the 20th century.

In 1870, Most and his associates were arrested by Austrian authorities, who were considered liberal but opposed to socialism, and charged with treason for their politics. His sentence was commuted in February 1871, but within a couple months (April 1871) Most was arrested for inciting a riot for preaching communism and was told to leave Austria by May 11 1871.

He headed back to Germany, which was now a unified empire. During his time there from 1871 to 1878, Most became a well-known figure in the Social Democratic Party, which was then debating economic theory; the theories of Marx and Engels were a dominant part of the conversation, but it would not be until 1891 that the party would adopt a Marxist economic programme. By then, Most would be in the United States and subscribing to anarchist politics.

In a manner similar to the status of communism, socialism and Marxism at the time, the theories of anarchism were hotly debated among its adherents. Like today, the politics of anarchy ran the gamut from an obsession with individual freedom to a politics that insisted on a democracy of all humanity under the popular rule of the laboring class.

Its most well-known figures were those given to fiery speeches, a lack of faith in electoral and legislative politics and, therefore likely to eschew traditional political organising aimed at party-building in favor of what is still known as the propaganda of the deed. This is an approach that argues for spectacular actions that simultaneously clarify the violence of the state while pushing the oppressed towards their liberation.

For a time Most became synonymous with the latter, rightly or wrongly. It was because of this association that he was arrested on that previously mentioned day in May 1886.

As Goyens points out, Most’s writing was both prolific and about much more than stirring people up to engage in actions falling under this category. Most of the writing published by Most during these years appeared in a German language paper called Der Freiheit; its intended audience was the German working-class community, especially those who identified as anarchists. He published this paper with his partner Helene Minkin.

In writing this book, Goyens (who also wrote an introduction to the 2015 edition of Storm in My Heart: Memories from the Widow of Johann Most) has written a political and personal biography of one of history’s more important socialists and anarchists. At a time when the international left attempts to make sense of the disruption all around us, this text provides an informative history of another time when capital was on a rampage.

Simultaneously, Johann Most: Life of a Radical goes a long way towards returning Johann Most, his words and his life to his proper place in the history of working people’s struggle against exploitation and for genuine democracy.

Ron Jacobs’s latest book, Nowhere Land: Journeys Through a Broken Nation, is now available. He lives in Vermont. He can be reached at: ronj1955@gmail.com