They Called it Peace

Lauren Benton

Princeton University Press, £35

HISTORIANS, who necessarily hope that their analyses and commentaries of the past may profit humanity in the future, are often upstaged by current events.

Lauren Benton’s study is designed to explore how efforts to place limits and controls on the behaviour of warring European nation states throughout the pre-imperialist and imperialist period, as they struggled to dominate and exploit the rest of the world, have rarely if ever been more than partially successful.

The ongoing, explosive Israeli killing spree, clearly unconcerned with war crimes and collateral damage (which an Israeli friend explained as “more land, fewer Arabs” when I visited the West Bank some years ago) has surely swept away any pretence at “legalising” warfare in the future.

Nevertheless, there is much of interest in her examination of how the perpetual tapestry of small wars, often paving the way for major conflicts, has been supported by arguments over what could constitute a just war.

From the Roman jurists to the Geneva Convention, intellectual attempts to temper the brutalities of warfare have accompanied self-interested slaughter.

These rules of war, building on Enlightenment thinking, were codified by the formal international institutions that include the League of Nations and the United Nations and, we are told, foreground attempts to outlaw and humanise war in the 20th century.

International lawyers have repeatedly found themselves struggling to justify “the value of a kind of law that must operate without an effective authority, a world state for example, to enforce it. We see at present the impotence of the United Nations security council.”

The first part of the book examines in early empires the role of maritime raiding and captive-taking and the development by early colonisers of “communities of households” which maintained their right to make local wars against indigenous societies. These local neighbours were defined as “enemies who could be attacked and killed anywhere without authorisation.”

Most raiding did not usually encompass slaughter, yet in all cases the division between plunder and something much worse led to the possibility of indiscriminate killing. Progressively these collections of “garrisons” became the “armature of empire.”

Benton draws on detailed examples from settler and colonial history, from the Portuguese in 16th-century India and English garrisons in the Caribbean, to the US wars against native peoples in 19th-century America.

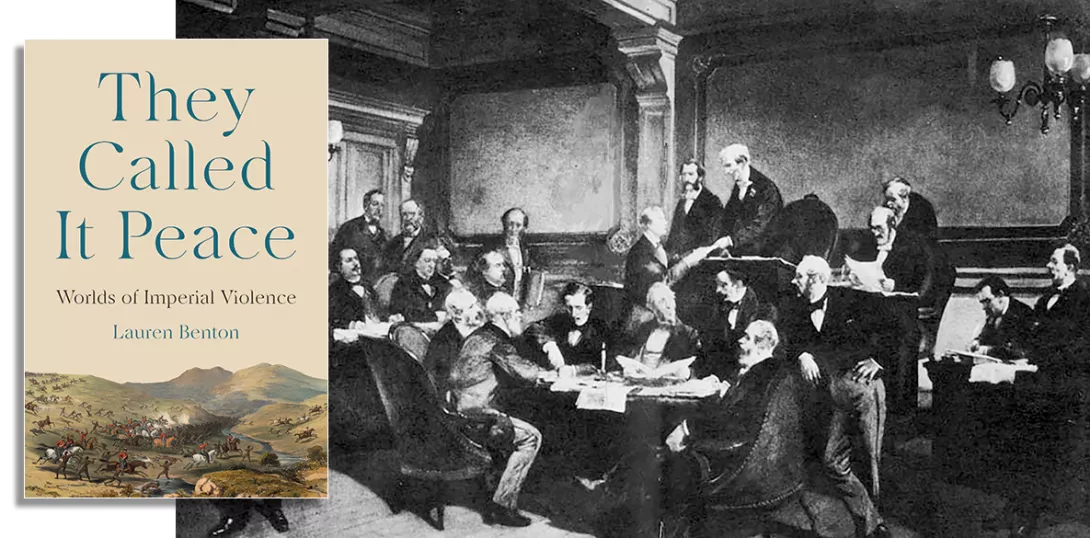

The second part deals with the defeat of Napoleon when the victors at The Congress of Vienna in 1815 encapsulated the vision of a European balance of power, which then served as a template for international order. Imperial interests were dressed in the camouflage of a legal framework relating to the use of violence against subject peoples. Treaties replaced references to natural war, just war and battlefield conduct.

The author’s position on what became the basis for a legal facade for gunboat diplomacy masking the continuation of imperial plunder, is clear from her reference to a description of the Law of Nations as “a sprawling discursive genre made up of patchy elements of doctrine; diverse strands of theological, legal, and political argumentation; and improvised narratives about the origins and nature of human sociability.”

Oddly, Benton does not mention the impact of the Holocaust and the dropping of the atomic bombs which seemed for nearly 80 years to have woken the world up to the realities of any future wars. Nor does she address the effects of aerial bombing on such issues as the protection of innocent civilians during war.

Human memory is short and any lessons learned from history are seemingly soon forgotten or, worse, ignored. Lauren Benton reminds us that “Familiar to us still, elastic discourses of self-defence and seemingly indestructible impulses for reprisal were packaged and repackaged across centuries.”

Daily, we are reminded that those packages are still being delivered.