SIMON PARSONS applauds an original, visual and movement-based take on the birth and death of a relationship

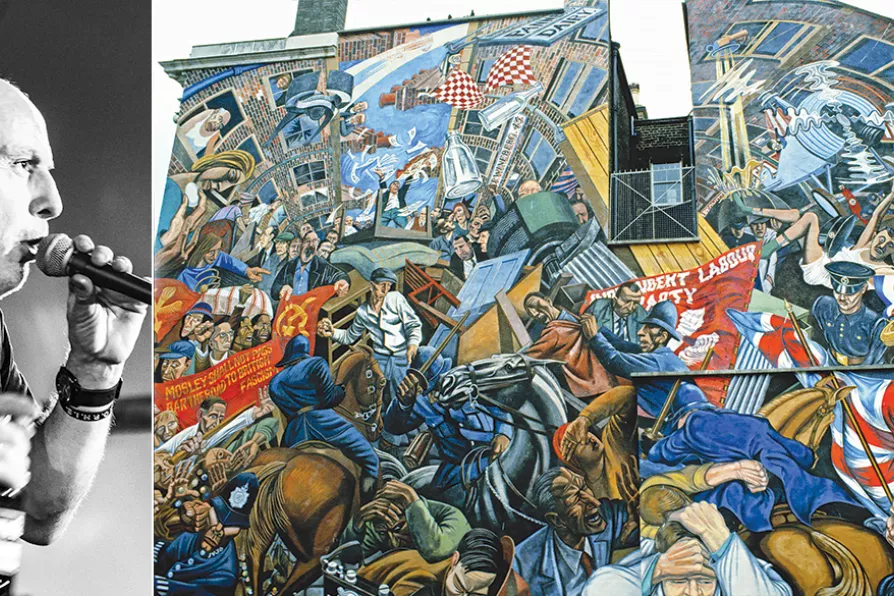

Punk poet Attila the Stockbroker in 2018; The Cable Street Mural in Shadwell, East London was painted on the side of St George's Town Hall by Dave Binnington, Paul Butler, Ray Walker and Desmond Rochfort between 1979 and 1983 to commemorate the Battle of Cable Street in 1936. The original design was by Dave Binnington

[Madchickenwoman/CC; Pic: Alan Denney/flickr/CC]

Punk poet Attila the Stockbroker in 2018; The Cable Street Mural in Shadwell, East London was painted on the side of St George's Town Hall by Dave Binnington, Paul Butler, Ray Walker and Desmond Rochfort between 1979 and 1983 to commemorate the Battle of Cable Street in 1936. The original design was by Dave Binnington

[Madchickenwoman/CC; Pic: Alan Denney/flickr/CC]

IN the 1980s, Britain’s far right was on the rise. Fascist parties fielded over 100 candidates in the 1983 general election. And culturally, the far right was also making ground.

“White power” bands like Skrewdriver and Peter and the Wolf began drawing sizeable crowds and selling thousands of records. In 1987, Skrewdriver’s frontman founded Blood & Honour, a music network that soon gained followers and branches throughout the US and Europe.

Blood & Honour’s emergence caused tremors among the UK anti-fascist movement. Anti-Fascist Action (AFA), the dominant anti-fascist group of the time, struck back with their own musical network: Cable Street Beat (CSB).

New releases from The Dreaming Spires, Bruce Springsteen, and Chet Baker

New releases from Mountain, Soul Asylum and Michael McDermott