MARIA DUARTE, LEO BOIX and ANGUS REID review Brides, Dead of Winter, A Night Like This, and The Librarians

What happens when the arts are democratised

GORDON PARSONS applauds a history of the US Federal Theatre Project, that brought political theatre to millions in the US

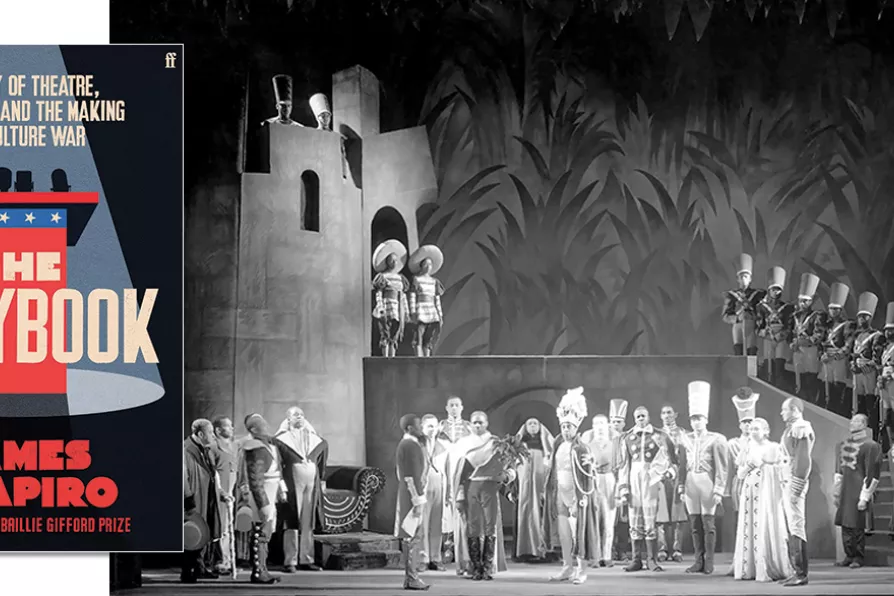

STUNNING: The arrival of King Duncan and his court at Macbeth's palace in Act I, Scene 2, of the Federal Theatre Project production of Macbeth at the Lafayette Theatre in April 1936

[Federal Theatre Project/LoC/CC]

STUNNING: The arrival of King Duncan and his court at Macbeth's palace in Act I, Scene 2, of the Federal Theatre Project production of Macbeth at the Lafayette Theatre in April 1936

[Federal Theatre Project/LoC/CC] The Playbook

James Shapiro

Faber, £20

IF it is to attract the attention of readers other than those interested in plays and playmaking, Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro’s compelling book certainly needs its subtitle, “A Study of Theatre, Democracy and the Making of a Culture War.”

The author, recognising this, prefaces his opening with dictionary definitions of the term “playbook,” including “A set of tactics frequently employed by one engaged in competitive activity.”

Similar stories

Between Musk’s bizarre British power grab and Trump’s overtly corporate agenda, modern robber barons face a growing backlash — and history shows how determined leaders can tame ultra-rich excess, writes STEPHEN ARNELL

A nervous year, showing that the theatre, like the world, stands on a precipice and seems uncertain where to jump

GORDON PARSONS negotiates an exhaustive biography of WH Auden that explores his growing detachment from England

JOHN GREEN marvels at the rediscovery of a radical US photographer who took the black civil rights movement to her heart

![REBELS: Ebada Hassan and Safiyya Ingar in Nadia Fall’s powerful debut feature Brides [Pic: IMDb]]( https://msd11.gn.apc.org/sites/default/files/styles/low_resolution/public/2025-09/round%20up%20web_0.jpg.webp?itok=qRcs4D1d)