GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends an important, if dispiriting book about the neo-colonial culture of Uganda under Yoweri Museveni

GAVIN O’TOOLE welcomes an eloquent and monumental history of the many different groups that have opposed imperialism with tactical violence

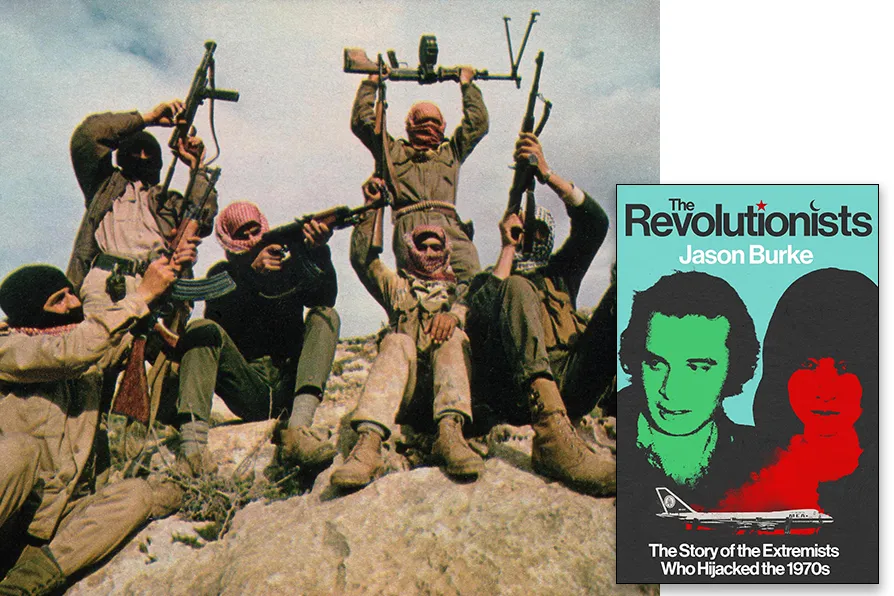

In the mountains east of the Jordan River, a patrol from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine punctuates a battle hymn with Soviet, Czechoslovak, and Egyptian weapons, 1969. [Pic: Thomas R. Koeniges/CC]

In the mountains east of the Jordan River, a patrol from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine punctuates a battle hymn with Soviet, Czechoslovak, and Egyptian weapons, 1969. [Pic: Thomas R. Koeniges/CC]

The Revolutionists: The Story of the Extremists Who Hijacked the 1970s

Jason Burke, The Bodley Head, £30

IT is an important time to be asking questions about terrorism, given a Labour government’s risible application of this label to pensioners holding placards and refusal to accept the self-evidently political nature of direct action to protest against genocide.

But what comprises “terrorism” has always been disputed, as shown by Jason Burke’s monumental history of the period between 1967 and 1983 in which this concept literally exploded into the social consciousness.

Burke has compiled an encyclopaedic narrative history of the people and organisations that hijacked, bombed and shot their way into posterity and the extensive links between them that enable their diverse activities to be examined under a single lens.

This volatile era can be considered a game of two halves, played out initially in the Middle East and western Europe at the height of the Cold War; and thereafter in a much wider theatre of conflict.

Its first stage was fuelled then, as now, by Israel’s ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians and land-hungry violence. Accordingly, the author traces the evolution of Palestinian resistance through high-profile hijackings by the PFLP and the growth of Fatah, eventually leading to the formation of the umbrella Palestine Liberation Organisation.

The German connection emerged from the creation of the far-left Red Army Faction, self-styled Marxist urban guerillas inspired by Palestinian attacks which they saw as viable expressions of revolutionary struggle against the imperialism embodied in the state of Israel.

A second, later sub-plot was the rise of Islamic radicalism in the aftermath of secular defeats as organisations from Tanzim al-Jihad to al-Qaida embraced armed action — a transition exemplified in the case of the Palestinians by the rise of Hamas.

Burke provides forensic and riveting accounts of key moments in this drama — the Revolution Airport spectacular in Jordan, the Munich Olympics attack, the siege of Opec in Vienna, Entebbe, Mogadishu, the seizure of Mecca’s Grande Mosque, the bombing of US facilities in Lebanon, and ultimately 9/11.

He tells the personal stories of many of those involved — from prominent figures such as George Habash, Wadie Haddad and Yasser Arafat to Ulrike Meinhof, Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin to the Ayatollah Khomeini, Farrokh Negahdar and Osama bin Laden — as well as of the cynical presidents who sometimes used them to fight their own feuds.

One character in particular stands out for doing the dirty work… for a fee: Carlos “The Jackal,” a vainglorious sybarite fired as much by personal ambition as ideological conviction, whose exploits thread throughout this book.

Importantly, Burke’s analysis straddles the transition from secular revolutionary violence and anti-imperialist national liberation struggles in the 1960s and ’70s, to the Islamic fundamentalism thereafter whose consequences we are still grappling with.

This transition was marked by revolutionary rivalry between secular organisations inspired by Marxism-Leninism and the guerilla strategies of figures such as Che Guevara, and those motivated by religious fervour. Occasionally, both came together in an uneasy alliance for pragmatic reasons, but as the case of Negahdar in Iran demonstrates, predatory behaviour in the revolutionary food chain would inevitably devour the weaker species.

Written with the sensibility of a journalist and fastidiously empirical, Burke’s history is an eloquent tour de force that will become an essential work of reference. If it does not investigate the phenomenon of terrorism in an overtly theoretical way, by exploring what drove the protagonists it will prompt reflection on a critically important question: whether this is ever a legitimate political activity.

The author cites many who insisted it was not, pointing to the attraction of Western politicians to a right-wing thesis first advanced by none other than Benjamin Netanyahu that there was no connection between revolution and terrorism.

Apply this observation to Britain and you will find a direct line of continuity between Margaret Thatcher rejecting the demands of Irish republican hunger strikers in the 1980s and Keir Starmer rejecting the demands of pro-Palestinian hunger strikers today.

But those who believe armed action can be legitimate will also find food for thought in the underlying warning ultimately articulated by Burke: we fail to understand the motivations of such revolutionists at our peril.