Releases from Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Maggie Nicols/Robert Mitchell/Alya Al Sultani, and Gordon Beck Trio and Quintet

JOSEPHINE BARBARO welcomes a diverse anthology of experiences by autistic women that amounts to a resounding chorus, demanding to be heard

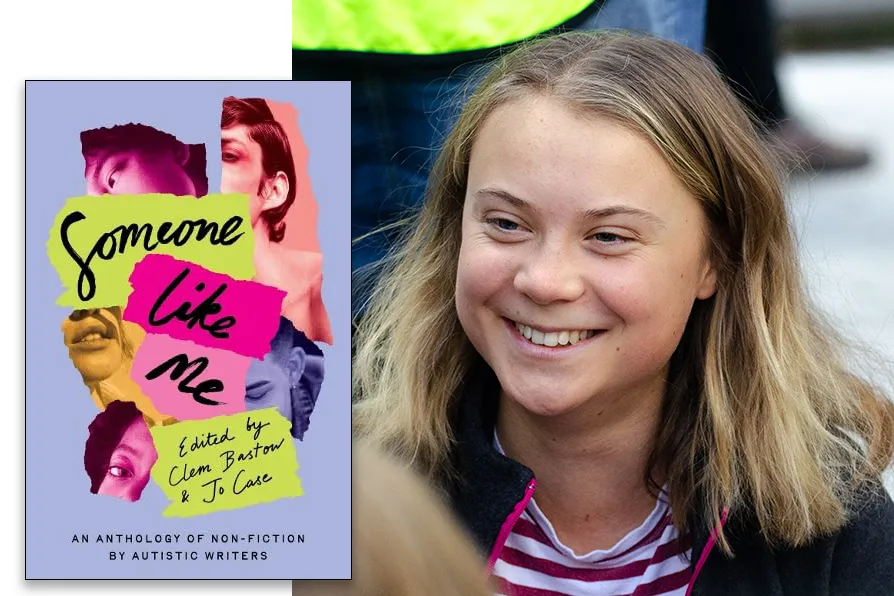

In 2021, Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg likened her autism to a "superpower", crediting her success to her focused interests [Pic: Frankie Fouganthin/CC]

In 2021, Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg likened her autism to a "superpower", crediting her success to her focused interests [Pic: Frankie Fouganthin/CC]

TRADITIONALLY, women and gender-diverse people were less likely to be identified as autistic because they didn’t fit the stereotype of how autism “should” look. This generalisation was based on research conducted with mostly young, white boys.

More women and gender-diverse individuals are now being identified as autistic: we have a better understanding of the many unique ways autism can present in people. This anthology contributes to this momentum, providing a platform for voices that have historically been overlooked and misunderstood.

The book captures the intimate experiences of 25 autistic women and gender-diverse writers. The impact of incorrect, missed or delayed diagnoses is threaded throughout, as are often-painful accounts of growing up in a world not built for neurodivergent people.

Issues such as intersectionality, mental ill-health, trauma, bullying and alienation are explored in these contributions. There are also accounts of the relief and contentment that come with a new (and often empowering) chapter of self-acceptance after identification.

Here the reader learns about the life-altering benefits of finding one’s “neurokin” (other autistic people), and the very real difference that support, self-acceptance and sensory accommodations (ie environmental tweaks such as adjusting lights or noise) can make.

Contributors to the book were encouraged to write in ways that felt natural to them, even if this meant straying from conventional expectations of structure or conciseness.

This editorial philosophy enables a refreshing authenticity. Diversity in communication styles is reflected in eclectic narrative techniques, fortifying one of the book’s central tenets: there is no “right” way to be autistic.

The crossover in author experiences underscores this collection’s political significance. Common themes include burnout, challenges with societal/cultural rules, trauma, (unrequited) love, systemic failure and the slow path to self-compassion. A lifelong sense of alienation echoes throughout these stories, something that, for many, only began to dissipate after self-identification/diagnosis.

Reading this book prompts reflection on the myriad ways our society contributes to failing autistic people. The school system, for example, (as investigated by one contributor, Sienna Macalister) is structured by, and measures success against, “even” learning trajectories based on year levels, rather than by the “spiky” learning profiles we often see in autistic kids, who struggle in some areas but skyrocket in others.

Misunderstandings in communication are often attributed to autistic “deficits,” rather than the misaligned communication that can occur between autistic and non-autistic people, sometimes known as the “double empathy” problem.

CB Mako’s work contemplates the intersection of ableism and colourism. The author reminisces about how their sister’s paler skin was revered, while the darkness of CB’s skin caused their family to worry for their future. Mako writes that they experienced ableism through belittling and taunting by peers and relatives, who pigeonholed them as less capable and less likely to succeed. By contrast, their sister was praised and highly valued.

Productivity as a measure of self-worth is explored in Danni Stewart’s and Erin Riley’s contributions on “crip time” and “autistic burnout” respectively. While the capitalist definition of “productivity” is a socially constructed concept, many autistic people push themselves beyond their capacity to “achieve” it, at the expense of their wellbeing.

To accommodate fluctuations in energy and ability, some autistic people embrace “crip time” — a disability-justice concept about bending time to match disabled bodies and minds. An example of this could be allowing autistic people extra time to complete tasks or work less or different hours. Yet, despite these internal adjustments, efforts to “keep up” often falter. Burnout will arrive, and the mask will fall.

The author writing under the initials LT, an autistic GP, details the heartbreaking realisation that the attributes that make her perfectly suited to her job — high focus on detail, her need for predictability and order and the intense care she gives her patients — also led her to extreme burnout. Under immense time pressure, driven by society’s “productivity” expectations, she had to sacrifice her own self-care to meet that of her patients.

Sometimes reclaiming the negative names we are called is a form of healing. Sara Kian-Judge’s essay flips the autistic experience of “not fitting in” into a celebration of the power of authenticity and uniqueness.

She writes: “Historically used to ridicule and ostracise people with physical, neurological and psychological differences, ‘freak’ dehumanised, and damaged my confidence. Today freak means openly living my differences and unmasking and healing. Once used to shame, freak now celebrates my strange eccentric ways of being.”

Indeed (as outlined in Fiona Wright’s piece), the irony of autism diagnostic reports is that the documented “deficits” are “all the things we like about each other!” Tangential conversation styles, oversharing, “info dumping,” special interests, pattern recognition and big feelings (to name a few) are the very things that connect autistic people and generate shared joy.

Someone Like Me provides deeply human insights into what it means to live in a neurotypical world as a neurodivergent person. It is not just a collection of stories — it’s a vehicle for advocacy that demands a broader, more inclusive understanding of difference.

Collectively they form a resounding chorus, louder and stronger together, which insists on being heard.

Josephine Barbaro is associate professor, principal research fellow and psychologist at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

This is an abridged version of an article republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence.

Please DO NOT REMOVE. —><img src=”https://counter.theconversation.com/content/252622/count.gif?distributor=republish-lightbox-basic” alt=”The Conversation” width=”1” height=”1” style=”border: none !important; box-shadow: none !important; margin: 0 !important; max-height: 1px !important; max-width: 1px !important; min-height: 1px !important; min-width: 1px !important; opacity: 0 !important; outline: none !important; padding: 0 !important” referrerpolicy=”no-referrer-when-downgrade” /><!— End of code

JULIA TOPPIN recommends Patti Smith’s eloquent memoir that wrestles with the beauty and sorrow of a lifetime

BLANE SAVAGE recommends the display of nine previously unseen works by the Glaswegian artist, novelist and playwright

Heart Lamp by the Indian writer Banu Mushtaq and winner of the 2025 International Booker prize is a powerful collection of stories inspired by the real suffering of women, writes HELEN VASSALLO

Reading Picasso’s Guernica like a comic strip offers a new way to understand the story it is telling, posits HARRIET EARLE