GLENN BURGESS suggests that, despite his record in Spain, Orwell’s enduring commitment to socialist revolution underpins his late novels

Taking the time to engage with the past

JAN WOOLF speaks to Richard Bradbury about his creative initiative in adult education, Riversmeet, and the political trajectory of the work

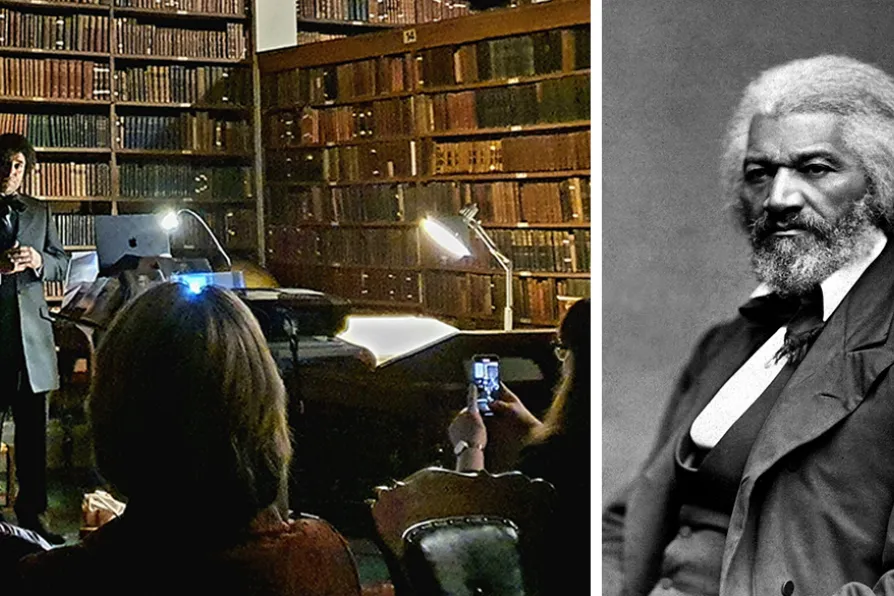

Nev Connor as Frederick Douglass at a rehearsed reading of The Ocean Can be A Bridge, by Richard Bradbury and Dave Samuels, in front of an invited audience from the local Caribbean, refugee and immigrant and refugee communities hosted by Art Share Exeter in Exeter Customs House

Frederick Douglass cca 1879

[Maureen Casey; George Kendall Warren/CC]

Nev Connor as Frederick Douglass at a rehearsed reading of The Ocean Can be A Bridge, by Richard Bradbury and Dave Samuels, in front of an invited audience from the local Caribbean, refugee and immigrant and refugee communities hosted by Art Share Exeter in Exeter Customs House

Frederick Douglass cca 1879

[Maureen Casey; George Kendall Warren/CC] NAMED after Richard Bradbury’s first novel about Frederick Douglass, the Riversmeet project combines literature with activism.

As the website declares, Riversmeet focuses on high-quality writing, performance and teaching which engages with contemporary issues by linking the past to the present.

Riversmeet is a quiet powerhouse; publishing books, producing theatre, short films and interesting blogs as well as running Slow Reading courses. Eschewing the tacky mission statement, it quotes Walter Benjamin: “In every era the attempt must be made anew to wrest tradition away from a conformism that is about to overwhelm it.”

Similar stories

CARL DEATH introduces a new book which explores how African science fiction is addressing climate change

The playwright and artist reflects on the ways in which reviewing can nourish the creative act

STEVE JOHNSON recommends the autobiography of the great US singer-songwriter and activist, Barbara Dane

ANDY HEDGECOCK recommends the application of ‘Gothic Marxism’ for its memorable portrayal of the physical violence done to working people