Durham Miners’ Association general secretary ALAN MARDGHUM speaks to Ben Chacko ahead of Gala Day 2025

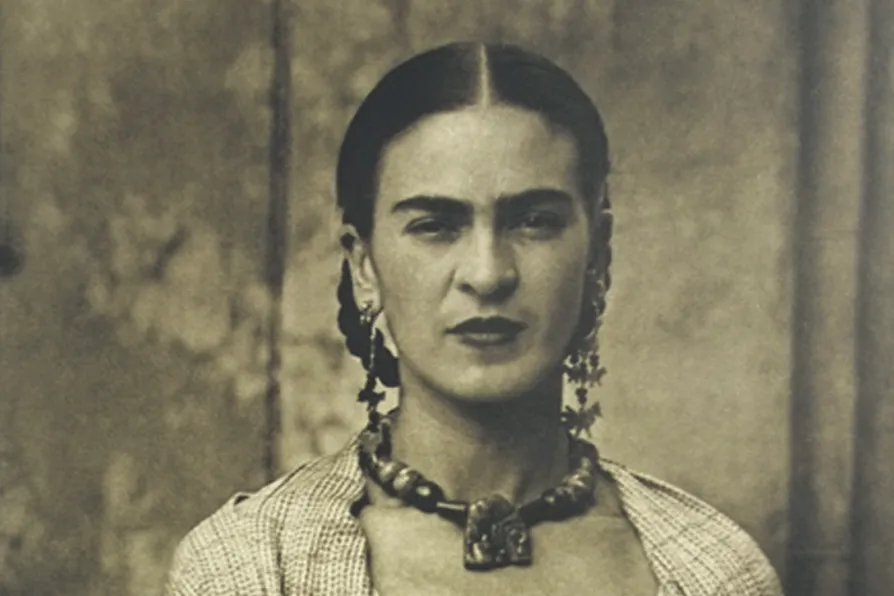

ABOUT 10 years ago, trapped in Dublin by those Icelandic volcanoes, I found I had time to visit an exhibition of an artist — Frida Kahlo — I had read about but never actually seen her paintings except in books.

Now at last I could see the actual gem like sparkling works.

Most were small, brightly coloured with frames that made them a bit like atheist religious icons.

Two rather pompous women with US accents were holding forth on what they thought about Kahlo.

“Rather full of herself, she seems only to have painted self-portraits and simplistic ones at that.”

I should have ignored them but rather foolishly I couldn’t hold back. I had to tell them: “That’s because she spent so long crippled, on her back and in a body cast.

“She was bed-bound for months with only a ceiling mirror and an easel her father had built so she could at least paint lying down and what she could see — herself.”

Rather smugly I thought I had won the argument, but how wrong can you be. The other woman responded with what she obviously thought was her killer blow. “Anyway she was a communist.”

“Yes,” I said, “and that was the best thing about her.”

Today Kahlo’s reputation is growing all the time even though she died 65 years ago this summer.

Her life was wracked with terrible ill health and she died aged just 47.

Even in her lifetime she was considered one of the Mexico’s greatest artists and Mexico has produced many fine artists.

Kahlo was born on July 6 1907 in Coyocoan, a village now part of Mexico City. Today because of the influence of its favourite daughter it has become the cultural hub of the city.

It houses the bright-blue Frida Kahlo Museum, showcasing her life and work, as well as the National Museum of Popular Culture and Folk Art. There are science museums, theatres and the Azteca Stadium hosts international football games.

Kahlo grew up in the family’s home later known as Casa Azul (the Blue House). Her father, a photographer of German origin, had come to Mexico where he met and married Matilde, half American-Indian and half Spanish.

Kahlo was just six when she contracted polio. She was bedridden for nine months and her right leg and foot withered. She would limp for the rest of her life an always wore long skirts.

Her father encouraged her play football, swim and even wrestle to help her recovery. He would also encourage her to help in his photographic business.

She proved very adroit at hand-colouring black and white prints.

One of very few female students at the National Preparatory School, Kahlo gained a reputation for being both outspoken and brave.

Here she first met the famous Mexican mural painter Diego Rivera — he was painting a mural on the school.

Kahlo often watched him work and she told a friend: “I will marry him some day.”

Kahlo joined a group of students who shared left-wing political views. They would sit up late into the warm Mexican nights discussing questions of identity, post-colonialism and Uncle Sam’s big bully state to the north.

They would argue about feminism, gender, class and race. It was at this time Kahlo, and many of her friends, joined what was then called the Party of Mexican Communists, as well as a group seeking to re-establish Mexican culture.

She fell in love with one of the group, a young journalist called Alejandro Gomez Arias, but tragedy struck.

In a bus and tram collision Kahlo was very seriously injured. A steel handrail went through her hip and both spine and pelvis were shattered.

After several weeks in hospital she was allowed home but had stay in bed wearing a full body cast for three months.

To alleviate both pain and boredom, Kahlo took up painting. Her father fixed a mirror to the ceiling above her bed and built an elaborate easel that allowed her to paint while lying on her back.

Not surprisingly, her first really impressive painting was a self-portrait. Frida said: “I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best.”

Kahlo met up with Rivera again in 1928. He praised her work and the two soon started a romantic relationship. Despite her mother’s objection, Kahlo and Rivera married in 1929.

The couple moved to wherever Diego could get a mural commission. The newly married couple lived in San Francisco, Detroit and New York, where the Museum of Modern Art held an exhibition of Rivera’s work.

Kahlo’s 1932 painting Henry Ford Hospital was painted in the US. She had had her second miscarriage and Kahlo painted herself lying naked on a hospital bed surrounded by a foetus, a flower, a pelvis and a snail, all connected by veins.

By 1933, Kahlo and Diego were living in New York. They both hated the capitalist culture of the US. Rivera had been commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller to create a mural.

The artist included Lenin in the painting. Rockefeller stopped his work and had Lenin painted over.

It was the last straw — they moved back to Mexico. Kahlo and Rivera’s marriage was never conventional. They keep separate homes and studios. Rivera had many affairs including one with Kahlo’s sister Cristina.

Kahlo was devastated when she found out and she cut off her long hair in desperation at the betrayal.

Kahlo always longed for children but the bus accident injuries made it very difficult. She had two miscarriages and both left her devastated.

Kahlo and Rivera often separated but they always went back together. In 1937 they befriended Leon Trotsky — exiled to Mexico.

The exiled couple stayed in Kahlo’s Blue House and Frida had a brief affair with Trotsky. She was briefly suspected of playing a part in his murder but was soon cleared.

Kahlo never considered herself as a Surrealist. She wrote: “Really I do not know whether my paintings are surrealist or not, but I do know that they are the frankest expression of myself.”

Her fame was growing. In 1938 she had a successful exhibition at New York City gallery. In 1939 she exhibited in Paris, making friends with artists such as Marc Chagall, Piet Mondrian and another communist, Pablo Picasso.

This Louvre in Paris was the first European museum to purchase a work by a 20th-century Mexican artist. The painting was The Frame by Kahlo.

She and Rivera divorced that year. Perhaps it was this that inspired one of her most famous paintings, The Two Fridas.

Just one year later Kahlo and Diego remarried. This second marriage wouldn’t differ much from the first. They still kept separate lives and houses. Both of them had frequent affairs.

In 1941, with Kahlo’s popularity growing, the Mexican government commissioned five portraits of important Mexican women. She never finished the project. The death of her father and continuing bad health made any serious work impossible.

1944 saw one of her most famous portraits, The Broken Column, which depicts Kahlo herself, bare-breasted and split in two, her shattered spine visible.

She wears a complicated surgical brace and there are nails piercing her breasts. It is art savagely imitating her tortured life.

Her health got worse and in 1950 came the news that she had gangrene in her right foot. She was bedridden for nine months with frequent hospital stays and operations.

Amazingly Kahlo still managed to work and paint. In 1953, she had a solo exhibition in Mexico.

Despite limited mobility she attended the opening ceremony, arriving by ambulance. She welcomed visitors from a bed set up among the artworks.

Just months later her right leg was amputated. She was to use a wheelchair for the rest of her life. Not surprisingly she suffered from acute depression, even becoming suicidal.

Despite these health issues, she remained politically active. She led a demonstration against US-backed overthrow of president Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala on July 2 1954. It was to be her last public appearance.

One week after her 47th birthday, Frida died at her Blue House.

The doctors said it was a pulmonary embolism, but many friends think Kahlo had simply had enough pain and misery and had chosen to end her own life.

In the late 1970s Kahlo’s work was rediscovered by art historians and political activists. By the early 1990s, she was recognised, not only as a great painter but also an icon for feminists, Mexicans and the LGBT movement.

Today her work is everywhere, and celebrated internationally as part of Mexican national and indigenous traditions.

Feminists increasingly see Kahlo’s art as an uncompromising view of the female experience.

Whether hanging in a posh gallery or printed on a T-shirt, more and more of us are enjoying her work, and that’s what Frida Kahlo — artist of the Mexican people — really would have wanted.