Getting those excitations

JAN WOOLF marvels at the dream-like forms of little-known English surrealist Henry Orlik, whose work reaches back to the traumas of war and migration

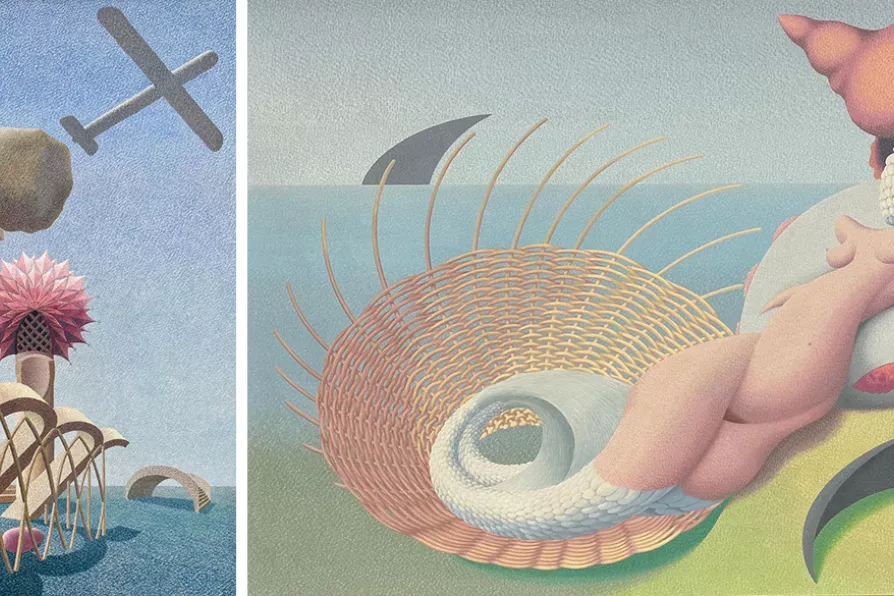

(L) Defeat (Aeroplane over LA); (R) Beauty and Sharks

[Henry Orlik and Winsor Birch]

(L) Defeat (Aeroplane over LA); (R) Beauty and Sharks

[Henry Orlik and Winsor Birch]

Henry Orlik, Cosmos of Dreams

Maas Gallery, London

LIKE me, you have probably not heard of the painter Henry Orlik. That’s because painting, not fame was his game. Eschewing the conceits of the art world, dealers took most of the money, leaving little for the artist.

A recluse for 50 years and now aged 77, Orlik has agreed to his first major retrospective, Cosmos of Dreams, at the Maas Gallery London, and later in his hometown of Marlborough.

The work is engrossing.

Similar stories

LOUISE BOURDUA introduces the emotional and narrative religious art of 14th-century Siena that broke with Byzantine formalism and laid the foundations for the Renaissance

This is poetry in paint, spectacular but never spectacle for its own sake, writes JAN WOOLF

While the group known as the Colourists certainly reinvigorated Scottish painting, a new show is a welcome chance to reassess them, writes ANGUS REID

JAN WOOLF wallows in the historical mulch of post WW2 West Germany, and the resistant, challenging sense made of it by Anselm Kiefer