ALAN McGUIRE welcomes the complete poems of Seamus Heaney for the unmistakeable memory of colonialism that they carry

GORDON PARSONS is fascinated by a unique dream journal collected by a Jewish journalist in Nazi Berlin

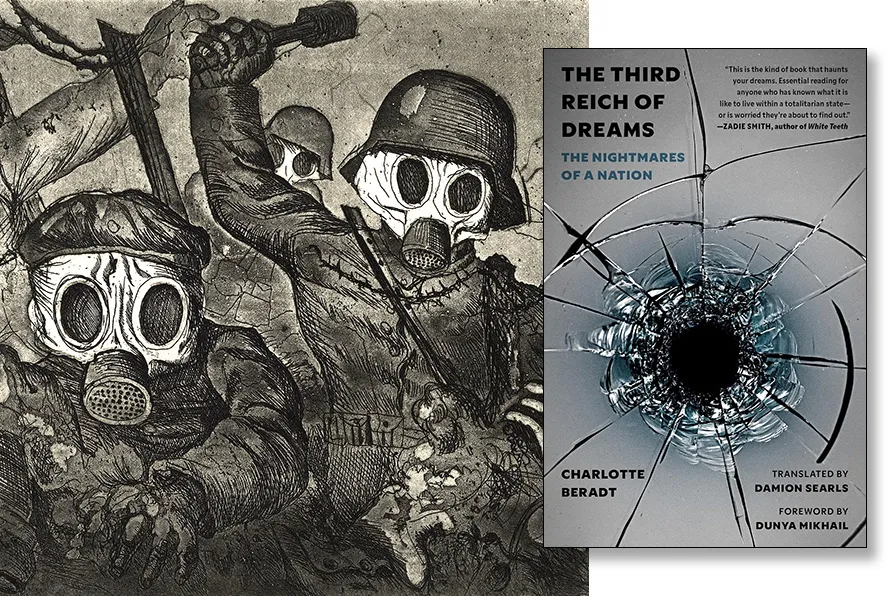

Detail from Stormtroops Advancing Under Gas, Otto Dix, 1924 / Pic: Public Domain

Detail from Stormtroops Advancing Under Gas, Otto Dix, 1924 / Pic: Public Domain

The Third Reich of Dreams

Charlotte Beradt, Princeton University Press, £20

DREAMS, from the earliest times, have been topics of fascination, and even fear. What do they mean? Why do we have them? Despite the psychoanalytical theories of Freud and Jung there are as yet no definitive answers. However it cannot be denied that, no matter how confusing, the events and emotions experienced in dreams must find their origin in the world of everyday reality.

Charlotte Beradt, a young, freelance, Jewish journalist working in Berlin in 1933 found herself trapped in nightly panic dreams which she recognised as responses to the Nazi nightmare the whole of her society were about to enter. Over the next six years, until the outbreak of war when she had to leave the country, she collected, with skill and courage, dream narratives of hundreds of her fellow Berliners.

“The Nightmares of a Nation,” the subtitle of this unique book eventually published in 1966, provides what is virtually a filmic account of the trauma, socially and psychologically, of the political metamorphosis of a society.

One can imagine the subtle delicacy with which Beradt must have teased out the subconscious and often terrifying experiences of those correspondents she felt able to trust. Among them, there were naturally no regime supporters, whose nightmares were presumably of a different order.

She organises approximately 70 short first person accounts into sections, reflecting differing responses to the totalitarian terror which both controlled the daytime and informed nightly dream experiences. The Social Democrat factory owner who struggles to raise his arm, “millimetre by millimetre” in salute during a visit by Goebbels, reflects the alienation and the identity crisis facing many of these dreamers, while the doctor whose personality resists the conformity enforced by the system finds all the walls have disappeared.

Sometimes the dream images are surreal. A middle-aged housewife is watched as a stormtrooper opens her stove which “started to talk in a penetrating voice. It said everything we’d said against the regime, every joke we’d told. God, I thought, what is it going to say next?“

There are those dreamers whose nightly experiences reflect a reluctant sense of “there’s nothing we can do” while others capture active opposition. Beradt comments: “I received several dreams where people actively working in the resistance… took decisive actions in their dreams too.” There is even one case of dream tyrannicide: “I often dreamed that I was flying over Nuremberg; I had a lasso, and with it I would fish Hitler out of the middle of the party congress and drop him into the English Channel.”

Power is erotic and Beradt includes a number of examples of women’s dreams with explicit erotic components, including one young sales girl describing how: “Goering was trying to feel me up at the movies. I said: ‘But I’m not even in the party’. He said: ‘I don’t care’.”

Beradt notes that the majority of the German public, dreamers or not, would submit to Gleichschaltung – the Nazi term for the imposition of total political and social control. For the Jews, however, there was no wish fulfilment escape into dreamland. Whereas the system worked to de-individualise Germans in general, it succeeded in many cases in destroying the sense of identity in many Jews. “There were two benches in the Tiergarten Park, one a normal green bench and the other painted yellow. [Jews were allowed to sit on only the yellow benches at the time.] There was a trash can between them. I sat on the trash can and hung a sign around my neck, the kind blind beggars sometimes have, which the authorities also make ‘race defilers’ wear. The sign said, ‘I’ll make way for the trash if needed’.”

This timely book makes for a marvellous companion piece to Victor Klemperer’s Diaries, I shall Bear Witness (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2009). Whereas they provide detailed records of daily existence in the Third Reich, Charlotte Beradt’s book reveals how that existence burrowed deep into that private world of dreams. Remember: “We are such stuff as dreams are made on.”

KEN COCKBURN relishes the memoir of a translator, but wonders whether the autobiography underlying the impulse would make a better book

JAN WOOLF is beguiled by the tempting notion that Freud psychoanalysed Hitler in a comedy that explores the vulnerability of a damaged individual

ANDY HEDGECOCK recommends that these beautifully written diaries from Gaza be essential reading for thick-skinned MPs

No excuses can hide the criminal actions of a Nazi fellow-traveller in this admirably objective documentary, suggests MARTIN HALL