MARJ MAYO recommends a lyrical and disturbing account of the tragic suicide in Venice of Pateh Sabally, a refugee from the Gambia

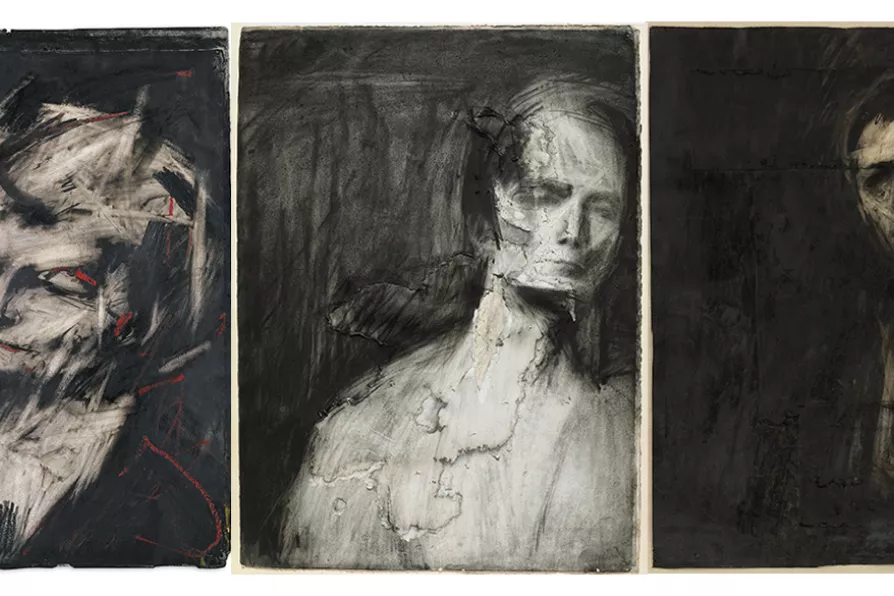

Head of Helen Gillespie II, 1962; Head of EOW, 1960; Self-Portrait, 1959

[© the artist - courtesy of Frankie Rossi Art Projects London]

Head of Helen Gillespie II, 1962; Head of EOW, 1960; Self-Portrait, 1959

[© the artist - courtesy of Frankie Rossi Art Projects London]

Frank Auerbach, The Charcoal Heads

Courtauld Gallery

“I FEEL there is no grander entity than the individual human being... I would like my work to stand for individual experience.”

This statement of Auerbach’s features prominently in his exhibition Charcoal Heads; drawings from the 1950s and ’60s being shown in this combination for the first time. Monumental but deeply human, it is this contradiction that makes them extraordinary.

Down and dirty with charcoal, stuff from burnt trees, trees that could have been from the forests of northern Europe where so much awful stuff happened, he gropes for the essence of a person. Frank Auerbach was sent to England aged seven by his German Jewish parents to save him from the Nazis. This is context!

JAN WOOLF ponders the works and contested reputation of the West German sculptor and provocateur, who believed that everybody is potentially an artist

JAN WOOLF examines work that aims to give viewers a material experience of the environments in the polar north and Britain equally affected by the climate crisis

JAN WOOLF finds out where she came from and where she’s going amid Pete Townshend’s tribute to 1970s youth culture