MARJ MAYO recommends a lyrical and disturbing account of the tragic suicide in Venice of Pateh Sabally, a refugee from the Gambia

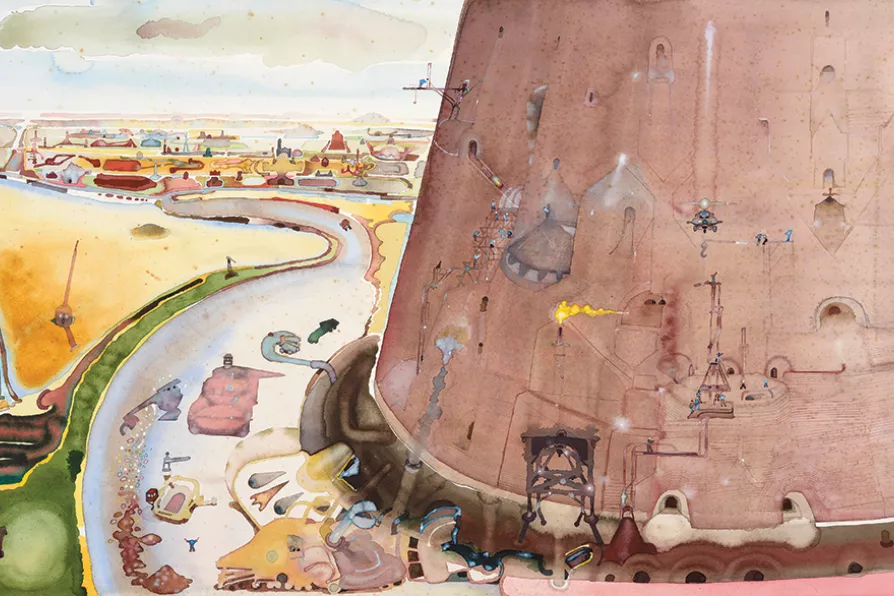

Tower of Babel, 1982

[Artist’s estate - courtesy of Liss Llewellyn and Three Highgate]

Tower of Babel, 1982

[Artist’s estate - courtesy of Liss Llewellyn and Three Highgate]

Twist and Shout

David Evans

Three Highgate, London

EPIC watercolour seems like a contradiction in terms, but that rather genteel medium, stereotyped by English evening classes and the Sunday morning easel was handled with vitality and drama by David Evans (1929-1988).

Resistance in watercolour is a juicy term coined by the exhibition’s curator Alistair Hicks, whose fine essay on Evans in the 2017 Liss Llewellyn Fine Art catalogue (on sale in the gallery) fixes his star in the constellation of post-war British art: among Edward Burra, Peter Blake and David Hockney.

Further back we find soulmates in Turner and Samuel Palmer in his landscapes. Well yes, male artists all, but at least pointing up that watercolour has balls.

Peter Mitchell's photography reveals a poetic relationship with Leeds