Releases from Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Maggie Nicols/Robert Mitchell/Alya Al Sultani, and Gordon Beck Trio and Quintet

HENRY BELL is fascinated by the underlying curiosities and contradictions of one of the great poets of the Mediterranean

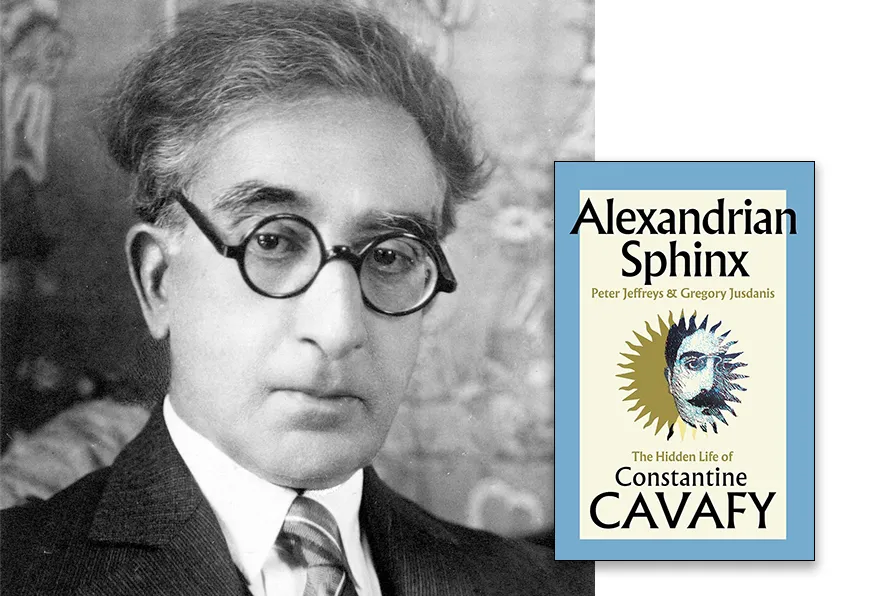

Cavafy in 1929, Alexandria [Pic: Public Domain]

Cavafy in 1929, Alexandria [Pic: Public Domain]

Alexandrian Sphinx: The Hidden Life of Constantine Cavafy

Peter Jeffreys and Gregory Jusdanis, Summit Books UK, £30

A BIOGRAPHER always finds himself part detective, part fantasist, part dilettante. The interests of the subject are never entirely aligned with those of the biographer. And no person ever fully reveals themselves in their archive. Often the interests of the subject and the biographer are entirely opposed.

Constantine Cavafy, one of the most beloved and most translated poets of the modern world, studiously recorded and edited his life. Preserving train tickets and burning letters, detailing family history and suppressing family secrets. Amidst this thick web of revelation and concealment, Peter Jeferies and Gregory Jusdanis try to chart the course of one of the great poets of the Mediterranean. Their book Alexandrian Sphinx, the first English language biography of Cavafy in 50 years, is a dense and rewarding read. In it they try to unravel Cavafy’s own strict programme of self-promotion and myth making, to reveal something of the world-renowned poet at the centre of it all.

Cavafy provides a specific challenge to the biographer in that this extraordinary poetic mind, this pioneering voice of queer love and lust, lived the staid and quiet life of a regional civil servant, in a provincial city, writing in a relatively obscure language. Add to this the fact that his life’s work hardly really began before middle age and Cavafy becomes an increasingly challenging subject.

Yet the underlying curiosities and contradictions are compelling. As when, at his death bed, Cavafy, the poet of hedonism and homo-eroticism, receives the final sacrament from the Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and all Africa. Or when, despite his reputation as aloof, isolated and self-interested, he dotes on the child of a friend, taking her to the theatre, and reciting poetry with her. As an adult she remembers that he smelled of cedarwood.

Cavafy considered himself a modern poet above all else, a poet for the future. And yet he comes to us from a lost time. The destruction of Palestine in 1948 and the consequent coups and revolutions in Egypt caused that country to lose its huge populations of Greek, Armenian, Jewish and Italian Egyptians.

These internationals had operated as a class apart, exempt from Egyptian laws and taxation. As such Cavafy is a cosmopolitan, diaspora Greek, speaking to us from an Ottoman past. Though his first language was English and he was raised in part in Liverpool, it is the Greek culture he encounters in Istanbul, where his family were refugees from the 1882 British bombardment of Alexandria, which cements him as a Greek poet.

For Cavafy, the British eventually secured his life in Alexandria through this bombardment, and the empire gave him employment as a civil servant. But his own subaltern identity as an Ottoman Greek led his sympathy and solidarity to be, at least in private, with the Egyptian peasantry. He wrote, in an unpublished poem in 1908, recording an outrage by the British in which they arbitrarily hanged four young villagers in the Nile Delta:

“When the Christians brought him to be hanged, / the innocent boy of seventeen, / his mother, who there beside the scaffold / had dragged herself and lay beaten on the ground”

The Christians are the evil-doers here, the Arab youth is innocent. And Cavafy’s sympathies throughout the poem are with the mother and the martyr. He is a Greek poet, but also a poet of the mixing and mixed eastern Mediterranean that the British were trying to pacify and categorise. His professional work was as a cog in that imperial machine, perhaps one of the reasons he chose not to publish the poem.

Elsewhere his journey from secret eroticism to overt homosexual identity in his poetry seems a great and bold risk, and certainly aligns him with the future, although there is always a relation between telling and hiding, revealing and disguising himself in his poetry and his letters.

These tightly bound contradictions and the ever present threat of bourgeois tedium lead the authors to write a non-chrinological biography, drawing the book out as a series of themes through which to glimpse the remarkable inner life of an outwardly ordinary man. Though this is rewarding in the depth it allows, it also sometimes has the effect of revealing only glimpses of Cavafy to us. Perhaps, however, that is all that is possible.

Cavafy is a poet who managed what we can know of his life just as tightly as he managed what we can know of his poetry. And it is amidst the poems that we really have a chance of knowing him.