JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

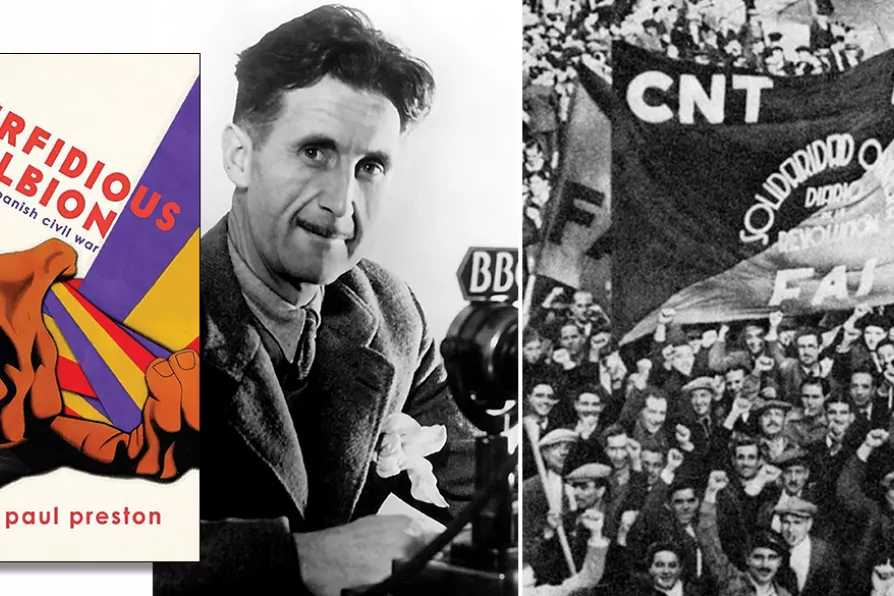

SKEWED VIEW: George Orwell at the BBC, 1940; and anarchists’ demonstration in Barcelona between 1936-37

[BBC/CC; Public domain]

SKEWED VIEW: George Orwell at the BBC, 1940; and anarchists’ demonstration in Barcelona between 1936-37

[BBC/CC; Public domain]

Perfidious Albion: Britain and the Spanish Civil War

by Paul Preston

The Clapton Press, £14.99

THIS new collection of essays by Paul Preston, the renowned historian of modern Spain, is very welcome. It is the perfect book for anyone seeking a dispassionate and scholarly introduction to the Spanish Civil War.

Today, right-wing politicians like David Cameron and his ilk again are invoking the spectre of appeasement which characterised Britain’s position on Spanish Civil War and gave Hitler the green light to invade Poland in 1939, but this time around as an argument for continuing to fuel the war in Ukraine by demonising Russia as the new Nazis. Never mind that it was precisely Cameron’s party forerunners who were the historical appeasers of fascism then, hoping to drive Hitler to invade Russia. Plus ça change!

Preston’s collection of essays here are timely in their recalling of that history. The first part focuses on the hypocrisy of British foreign policy towards Spain and which was instrumental in helping Franco defeat the Republic. And it was the Conservative Party, imbued with its hatred and fear of communism and “Russian barbarism” which took the lead then as now.

Spanish dictator Francisco Franco died 50 years ago today November 20. JIM JUMP looks back at his blood-soaked rule and toxic legacy on Spain today

STEVE ANDREW enjoys an account of the many communities that flourished independently of and in resistance to the empires of old

TONY FOX invites readers to come and hear the story of the remarkable Liverpudlian International Brigader Alexander Foote

LYNNE WALSH tells the story of the extraordinary race against time to ensure London’s memorial to the International Brigades got built – as activists gather next week to celebrate the monument’s 40th anniversary