MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review "Wuthering Heights", Little Amelie or the Character of Rain, Crime 101, and Stitch Head

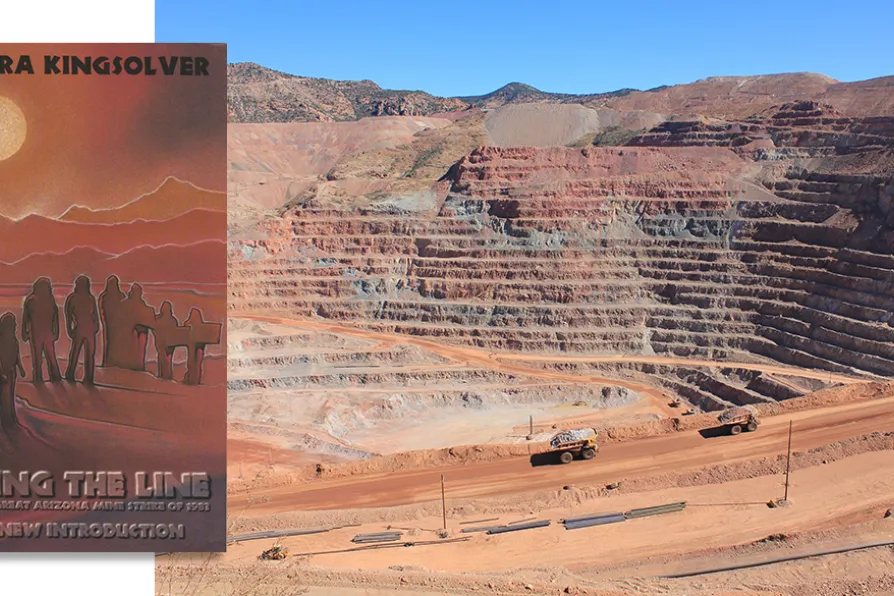

Morenci Mine in Arizona, United States. Morenci represents one of the largest copper reserves in the world, with estimated reserves of 3.2 billion tonnes. From 1983 to 1986, workers at Morenci and three other mines went on strike due to layoffs impacting most of the workers at the mine following a large drop in the price of copper. The strike involved numerous violent confrontations between workers and hired strikebreakers. The strike completely failed in 1986 after the NLRB rejected appeals by the unions to halt the campaign of decertification against them.

[Stephanie Salisbury/CC]

Morenci Mine in Arizona, United States. Morenci represents one of the largest copper reserves in the world, with estimated reserves of 3.2 billion tonnes. From 1983 to 1986, workers at Morenci and three other mines went on strike due to layoffs impacting most of the workers at the mine following a large drop in the price of copper. The strike involved numerous violent confrontations between workers and hired strikebreakers. The strike completely failed in 1986 after the NLRB rejected appeals by the unions to halt the campaign of decertification against them.

[Stephanie Salisbury/CC]

Holding the Line – Women in the Great Arizona Mine Strike

Barbara Kingsolver, Faber & Faber, £16.99

THE 1983-84 Phelps Dodge Coppermine Strike may not be well-known here but it gained a significant place in American labour history.

Phelps Dodge ran four copper mines in Arizona; Morenci and Ajo were company towns where all municipal functions, services and housing were run by the company, who even vetted the books in the library.

Mexican-Americans comprised about 40 per cent of the population of Morenci. Hispanic miners could only achieve the status of “labourer,” earning less than their non-Hispanic workmates. The segregation of Mexicans was felt in housing, education and social venues; Ajo’s swimming pool was only open to them late on Wednesdays just before the weekly change of water.

PAUL BUHLE agrees that a grassroots movements for change in needed in the US, independent of electoral politics

STEVEN ANDREW is moved beyond words by a historical account of mining in Britain made from the words of the miners themselves