GEOFF BOTTOMS applauds a version set amid the violent conflicts of the 19th century west African Oyo empire before the intervention of British colonialism

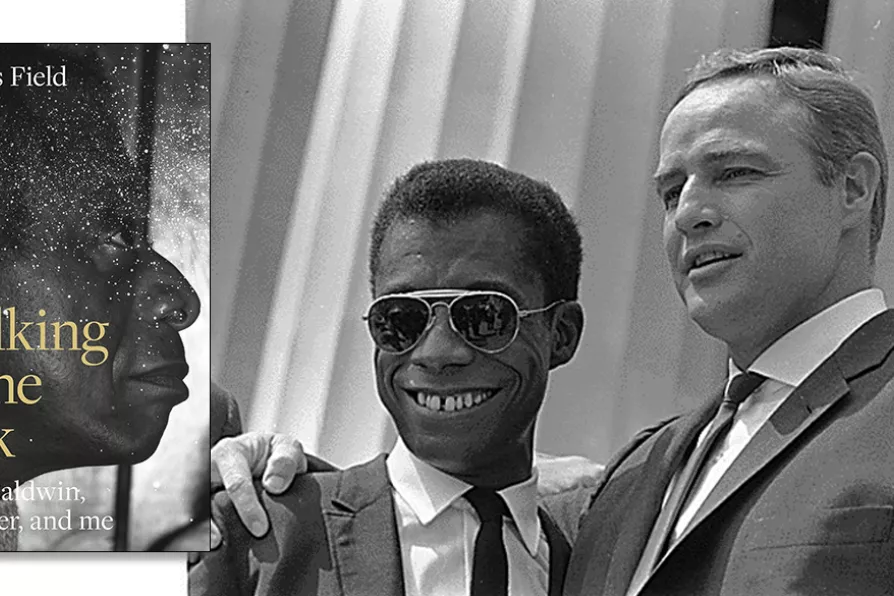

James Baldwin and actor Marlon Brando, Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. 08/28/1963

[US Information Agency/CC]

James Baldwin and actor Marlon Brando, Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. 08/28/1963

[US Information Agency/CC]

Walking in the dark

Douglas Field, Manchester University Press, £16.99

Douglas Field’s Walking in the dark is a personal exploration, intertwining his life with the writings of James Baldwin. At the heart of this work lies a meditation on memory, history, fathers and sons, with the shadow of Alzheimer’s disease looming large.

Field’s preoccupation with Alzheimer’s, particularly through the lens of his father’s suffering, serves as a central theme in the book. Baldwin’s reflections on memory and history are brought into conversation with Field’s struggles to understand his father’s illness. However, one might question where Baldwin truly fits into this exploration. The connections between Baldwin’s writings on memory — especially his view that history is largely a record from the victor’s perspective — and Field’s personal narrative are somewhat tenuous.

MARJORIE MAYO welcomes an account of family life after Oscar Wilde, a cathartic exercise, written by his grandson