In his second round-up, EWAN CAMERON picks excellent solo shows that deal with Scottishness, Englishness and race as highlights

Bay Area Reds

PAUL BUHLE recommends a thorough and necessary history of communist organisation and the difficulties it faced in California

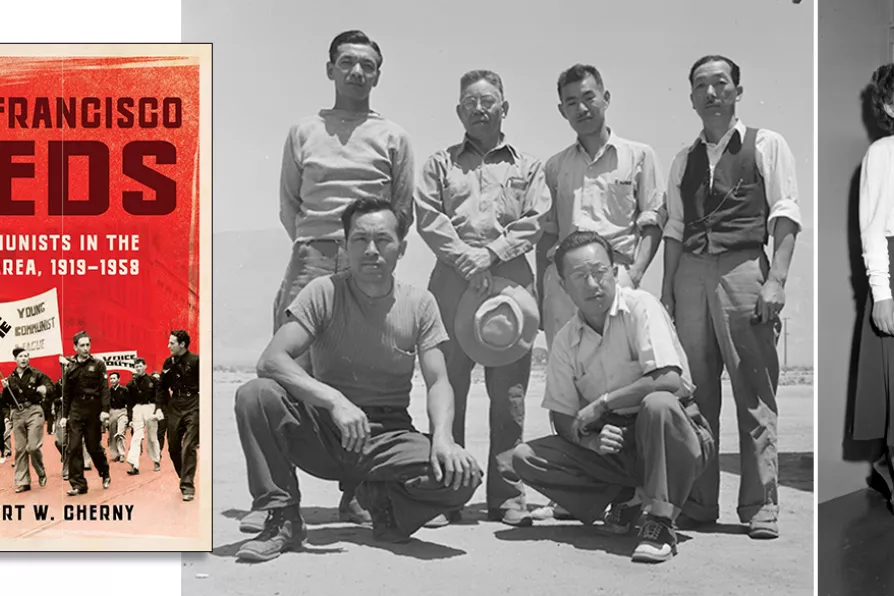

(L) Manzanar Relocation Center, California, May 29 1942. A group of Block Leaders who are drawing up the Constitution for this War Relocation Authority center - front row (L to R) Karl Yoneda [communist], H. Inouye; back row, (L to R) Bill Kito, Ted Akahoshi, Tom Yamazaki, and Harry Nakamura; (R) Dorothy Healey, chair of the CPUSA in Southern California, standing before jail cell in Los Angeles, California, June 29 1949

[Francis Stewart/War Relocation Authority/Public domain; Los Angeles Daily News/Los Angeles Times photographic archive UCLA Library/Public domain]

(L) Manzanar Relocation Center, California, May 29 1942. A group of Block Leaders who are drawing up the Constitution for this War Relocation Authority center - front row (L to R) Karl Yoneda [communist], H. Inouye; back row, (L to R) Bill Kito, Ted Akahoshi, Tom Yamazaki, and Harry Nakamura; (R) Dorothy Healey, chair of the CPUSA in Southern California, standing before jail cell in Los Angeles, California, June 29 1949

[Francis Stewart/War Relocation Authority/Public domain; Los Angeles Daily News/Los Angeles Times photographic archive UCLA Library/Public domain] San Francisco Reds: Communists in the Bay Area, 1919-1958

Robert W. Cherny, University of Illinois Press £22.05

THE story of the US left has been pretty much ups and downs, something hardly surprising in world capitalism’s leading nation with a working class historically divided by race and ethnicity.

Among the most startling cases is surely the California Story.

The California Socialist Party of pre-1920 days elected mayors, guided at least some craft unions, had quite a following among displaced Yankees and a scattering of ethnic groups. The rough conditions of what would one day become known as the Left Coast meanwhile prompted IWW-like, semi-anarchist labour activism.

Similar stories

PAUL BUHLE agrees that a grassroots movements for change in needed in the US, independent of electoral politics

HELEN MERCER welcomes an account of how US labour leadership collaborated with the state and betrayed their membership

PAUL BUHLE recommends an exhaustive guide to the grand ambition of bringing revolutionary workers together in a global unitary body

JOHN GREEN marvels at the rediscovery of a radical US photographer who took the black civil rights movement to her heart