GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends an important, if dispiriting book about the neo-colonial culture of Uganda under Yoweri Museveni

JOHN WIGHT celebrates a new account of the life of the great British boxer and communist Len Johnson

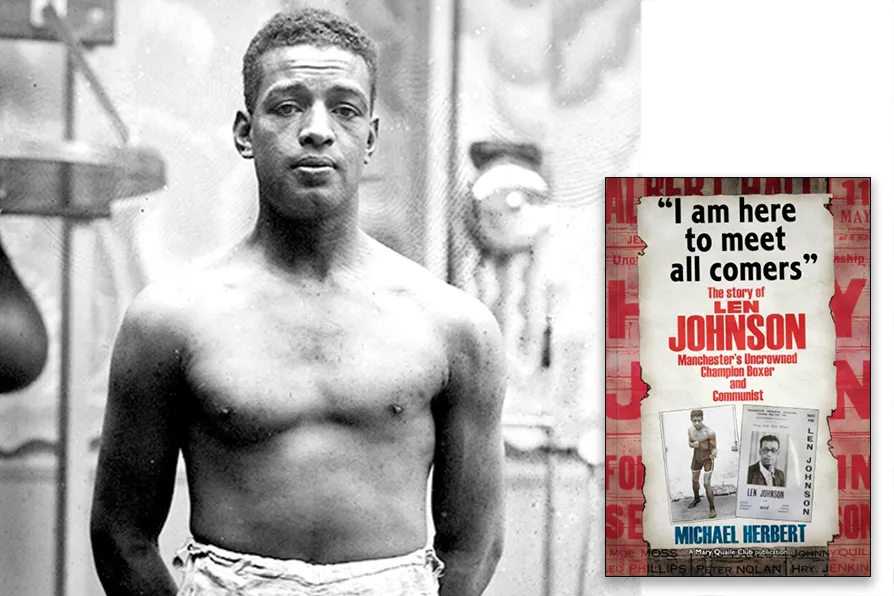

CLASS WARRIOR: Len Johnson, 1932 [Pic: Bibliotheque nationale de France/CC]

CLASS WARRIOR: Len Johnson, 1932 [Pic: Bibliotheque nationale de France/CC]

I am here to meet all comers

Michael Herbert, Lulu, £11.95

If any proponent of the noble art has ever deserved their story to be told, it is Manchester’s Len Johnson.

Johnson was born on October 22 1902 in Clayton, Manchester, to an Irish mother and a father from Sierra Leone. His boxing career lasted a decade, between 1923 and 1933, and he fought an astounding 134 bouts, winning 95, losing 12 and drawing seven.

Yet despite this remarkable record, he was prevented from fighting for a British title by the British Boxing Board of Control under the board’s then racist Rule 24, which mandated that only fighters born from white British parents could do so.

This particular rule was added to the board’s constitution in 1911 with government backing, and it remained extant until 1948. In the year it was removed, Dick Turpin became Britain’s first black champion, and Turpin’s brother Randolph, who also fought at middleweight, would subsequently go on to become world champion in 1951, defeating the legendary Sugar Ray Robinson in London.

The point is that without the prolonged struggle waged by Johnson and his supporters, wonderfully among them Paul Robeson, against the colour bar in British boxing, the feats of Dick and Randolph Turpin would not have been possible.

Herbert writes: “The official racism directed at Len Johnson and other black boxers was intimately linked to Britain’s role as an imperialist world power in the 19h and 20th centuries.”

Johnson’s early education in the sport took place as a teenager in the boxing booths that were a fixture of travelling fairs across Britain at the time. It was there that he developed the defensive skills necessary to survive against men considerably older and stronger.

In 1925 he defeated reigning British middleweight champion Roland Todd twice in just seven months. That same year, Johnson also faced and defeated Ted “Kid” Lewis, whom Mike Tyson once claimed was the best fighter to ever come out of Britain. Yet, due to the board’s colour bar, these fights were fought as non-title bouts.

Understandably frustrated at his inability to fight for a title and have his achievements in the ring recognised in Britain, in 1926 Johnson decamped for Australia, where he faced and defeated Harry Collins to win the Empire (now Commonwealth) middleweight title, but even this was not recognised in Britain.

However, Johnson was embraced as a local hero in Manchester, and meeting Paul Robeson in 1932 in Manchester proved a seminal moment. Robeson urged Johnson to mount a legal challenge against the British Boxing Board of Control. He also inspired him politically, to the extent that Johnson, after retiring from boxing, joined the Communist Party of Great Britain.

In this capacity, along with fellow Manchester communists Wilf Charles and Syd Booth — the latter a veteran of the Spanish civil war — he helped establish the New International Society (NIS) in Moss Side.

The aim of the NIS was the championing of the universal application of human rights regardless of skin colour, gender, religion or ethnic background. It became a prominent civil rights organisation in postwar Britain, campaigning against and exposing racist employers and discriminatory housing policies, among other racial injustices that were prevalent at the time.

In 1949, Johnson again met Robeson in Manchester while the latter was in Britain touring the country to raise awareness of the plight of the Trenton Six. Inspired by Robeson, Johnson became active in the cause of Pan-Africanism, to the point of being chosen to be one of the local delegates to the Fifth Pan-African Congress, held in Manchester at Chrolton-upon-Medlock Town Hall between October 15-20 1945.

That congress brought together 87 delegates representing 50 organisations from across the world. Among the most prominent delegates in attendance were Kwame Nkrumah and Jomo Kenyatta, both of whom would go on to lead successful anti-colonial struggles in Africa.

In 1953, Johnson himself led a movement that successfully ended the discriminatory policy followed by pubs across Manchester. After the landlady of he Old Abbey Taphouse refused to serve him, as he knew she would, along with his friend and comrade Wilf Charles, he mobilised a crowd of 200 to descend on the place in protest. In response, the landlady backed down, prompting a chain reaction across the city.

The Old Abbey Taphouse is today a community pub where the lives of Johnson and Charles are celebrated. A campaign to raise money to erect a monument in Johnson’s memory has drawn the support of various local dignitaries, including Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham.

One of Britain’s finest fighters inside the ring and one its greatest fighters against racial injustice outside it, Len Johnson died in 1974 at age 71, and today a campaign to raise money to erect a monument in Johnson’s memory has drawn the support of various local dignitaries, including Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham.

I Am Here To Meet All Comers will be launched on Saturday 24 January, 2pm, at The Lounge, Methodist Central Hall, Oldham Street, Manchester. More information: maryquaileclub@gmail.com