GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends an important, if dispiriting book about the neo-colonial culture of Uganda under Yoweri Museveni

Given the epidemic of corruption in post colonial states, ALEX HALL is disappointed by a failure to analyse the economic architecture that makes it so lucrative

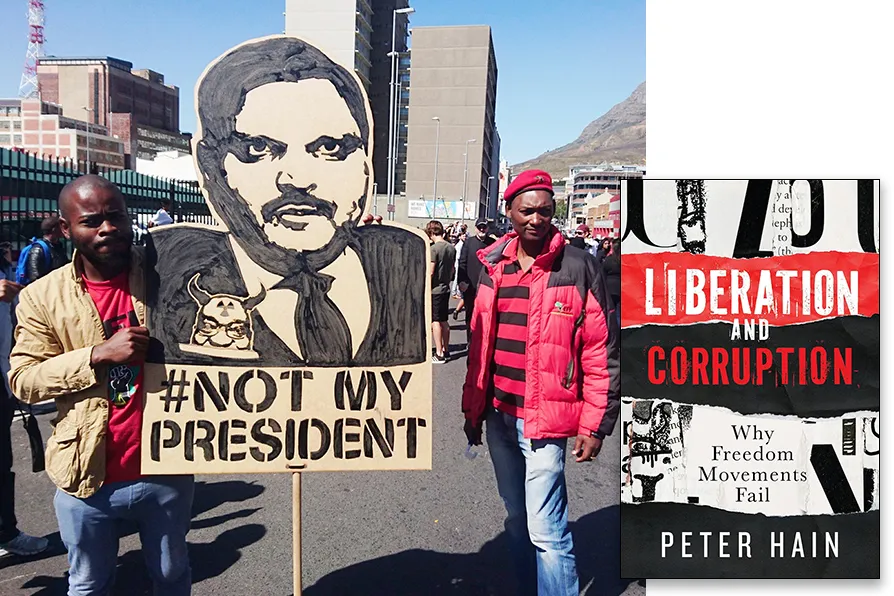

A placard depicting South African businessman Atul Gupta at a protest against corruption during the Zuma administration. [Pic: Discott/CC]

A placard depicting South African businessman Atul Gupta at a protest against corruption during the Zuma administration. [Pic: Discott/CC]

Liberation and Corruption: Why Freedom Movements Fail

Peter Hain, Policy Press, £12.99

ANYONE influenced by Marxism — or indeed any social change theory — would have looked at the subtitle and hoped for some serious guidance on how to maintain the new order once the old order had been overthrown. Alas, look elsewhere.

Peter Hain — he of anti-apartheid activist and then New Labour fame — examines a number of cases where the overthrow of the colonialist state failed to live up to expectations. He has a particular focus on his native South Africa, in particular examining the failures of the Zuma regime and the end-of-term regrets of Nelson Mandela.

To cut to the chase – it’s about corruption. The leaders of the new state are too easily tempted by graft to stick to the programme, and thus the ideal slips from the fingers of the newly enfranchised. That’s it and, basically, we need better regulation to put it to a stop, such as an international court of corruption which will have all the powers it needs.

The narrative is weakened by failing to provide any definition of freedom, as in “freedom movement.” Yes, overthrowing the laws of the old state was a definite goal of anti-apartheid. But in the end was it merely the franchise and a new flag? Or should freedom mean freedom from want, landlords and unaccountable private power?

Seizing the reins of power is the proximate goal of all liberation movements. The new regime wields the powers of the state, with a sense of relief and consensus settling over the populace. Sometimes this happens through military defeat, sometimes through political pressure and sometimes through negotiation.

The South African case was a mixture of all. Ultimately, the handover of power into a democratic state, with a new, consensus-generated constitution, was something brought into being by tenacious resistance, but the power shift was also negotiated at the end. Any type of workers’ control was seen off even before Robben Island was first reimagined of as a tourist attraction.

So you can vote for a new parliament. But can you vote for your boss, your landlord or your banker? What about any of those that own the resources you need to access — those who you can’t vote for or against?

The question of “what type of freedom” is essentially left unframed, while the solution that Hain comes to is simply: better regulation of capitalism. But if international law is powerless to stop a genocide, how would it tame a multinational corporation’s “de-banking” of a state?

Hain recognises one source of corruption: corporate interests. Indeed, he makes a solid case for those evils in many states, in Africa and beyond. The Bribery Act in Britain specifically excludes defence contracts from its terms, for example. Hain asks how might we better regulate capitalists. But Tony Benn might ask: how did they get this power, in who’s interests do they exercise it, and how can we vote them out?

Without asking these questions it all becomes a question of marginal prosecution of dodgy capitalists. As such, Hain’s work is a catalogue of post-liberation graft, but a failure to analyse the economic architecture that makes corruption so lucrative.

Why is the default model for the state one of procurement from profit-seeking private entities (and the policing of that for corruption), rather than the cultivation of public capability? Why is private ownership itself beyond the boundary of debate? And most obviously for Britain, why is the defence sector granted a licence for colossal spending and a free pass for corruption?

Seizing a state is one thing. Freedom is another.